A $23 Billion Law Firm? New Valuation Model Says Kirkland Fits the Bill

Hunton Andrews Kurth CFO Madhav Srinivasan came up with a formula to apply Wall Street-style scrutiny to law firms.

May 23, 2019 at 05:30 AM

4 minute read

Image: BigStock

Image: BigStock

The legal industry tends to hold itself apart from the rest of the corporate world. But with talk of allowing outside investment in law firms gaining steam both inside and outside the U.S., Hunton Andrews Kurth CFO Madhav Srinivasan decided to subject firms to an exercise that's routine in other enterprises: pinning a dollar value on their business.

Srinivasan, who also lectures at Columbia Law School, spent nearly two years building and testing a methodology for valuing law firms before applying it to the firms in the Am Law 100 in a report for ALM Intelligence.

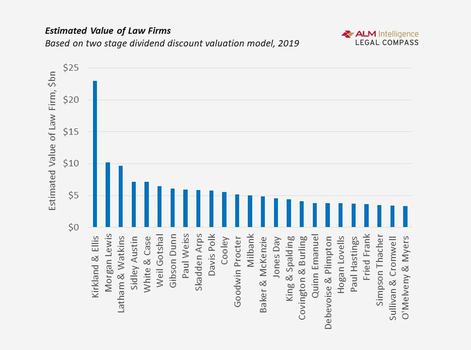

Just as in a number of recent industry rankings, Kirkland & Ellis came out on top. But here, the results are eye-popping. According to Srinivasan's calculations, the firm is worth almost $23 billion, more than twice as much as Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, the second-highest-valued firm.

Click image to enlarge

Click image to enlargeThe approach differs from more traditional efforts to rank and evaluate law firm financial performance, which focus on past results.

“Nobody's done forward-looking stuff before. I'm going out on a limb,” Srinivasan said. “I've shown how the sausage is made. People can either agree with it or not.”

The veteran financial analyst, who has worked at two other major international law firms as well as in industry, acknowledged that former American Lawyer reporter Chris Johnson put together a model for valuing law firms in 2012. But he said that the time was ripe for an even more rigorous attempt, putting to use Wall Street evaluation techniques.

Srinivasan ultimately arrived at a six-step approach, starting with separating partner compensation into two categories: salary and “at risk” income. Taking the aggregate of the latter as the firm's profit, he then subtracted a sum for taxes to arrive at net income. For the Am Law 100 in the aggregate, these calculations yielded a net income margin of 11.8%.

He then paused to see if this figure made sense. While far below the combined profit margin for the 2018 Am Law 100 of 40%, it was in line with two peer groups with publicly available valuation figures: publicly traded U.S. consulting firms and publicly traded U.K. and Australian law firms. With a data set of the former yielding a net income of 8% and a data set of the latter yielding 13%, Srinivasan saw his figures were comparable and knew he was on the right track.

The final steps involved using standard accounting techniques to project cash flow over the next five years and then a terminal value at the end of year five, using a firm-specific growth rate, and finally arriving at an individual valuation of each law firm.

One limitation of the model, as Srinivasan acknowledges, is that it relies on the assumption that growth will continue at a fixed rate based on recent history for a given firm.

“If there's a recession, I cannot predict if profits will fall,” he said.

But he didn't do his work in a vacuum. Srinivasan sent off his work to experts in valuations, including professionals at Deloitte and PwC and an academic at the Wharton School.

“This went through many iterations,” he said.

For now, Srinivasan's exercise is purely academic. While there's growing talk about regulatory change, nonlawyers are currently barred from owning or investing in U.S. law firms.

The results should still spark a conversation, as Srinivasan says they shed light on firms with comparable historical financials. Those with a higher value are likely doing more things right.

That opens the door to a challenge that's messier than assembling a valuation model: determining what those things are, and finding ways to implement them.

Read More

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Covington, Steptoe Form New Groups Amid Demand in Regulatory, Enforcement Space

4 minute read

Consumer Finance Law Enforcer Takes Private Practice Job at Morgan Lewis

With 'Fractional' C-Suite Advisers, Midsize Firms Balance Expertise With Expense

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250