Diversity Scorecard: African American Lawyers Are Being Left Out

Despite some minority growth in Big Law, African American attorneys are still not gaining representation.

May 28, 2019 at 05:30 AM

9 minute read

Editor's note: After this article was published in the June edition of The American Lawyer, Turo CLO Michelle Fang released a set of actionable steps for general counsel looking to promote diverse legal talent.

As minorities see incremental growth in representation within Big Law, black attorney ranks have remained mostly stagnant for nearly a decade, according to The American Lawyer's 2019 Diversity Scorecard. And despite a renewed push for diversity among in-house counsel, black lawyers don't anticipate sudden changes without a measure of accountability among law schools, law firms and clients.

Since 2011, black lawyers have seen both the slowest growth among the Am Law 200's ranks—from 3.1 percent to 3.3 percent—and the lowest levels of representation when compared with other minority groups, such as Asian Americans and Hispanics. In that time, total minority representation has risen from 13.6 percent to 16.9 percent.

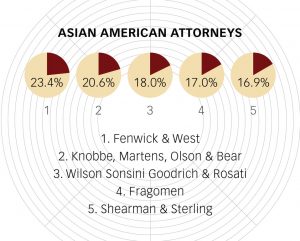

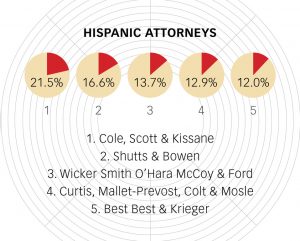

While most diversity experts would agree that representation among minorities remains far below parity with the total U.S. population, Asian American and Hispanic attorneys make up 7.3 and 4.1 percent of Big Law benches, respectively. Additionally, both have seen a 1.1 percent uptick in representation since 2011.

While most diversity experts would agree that representation among minorities remains far below parity with the total U.S. population, Asian American and Hispanic attorneys make up 7.3 and 4.1 percent of Big Law benches, respectively. Additionally, both have seen a 1.1 percent uptick in representation since 2011.

Black associates and partners are underrepresented even among the top performers on this year's Diversity Scorecard.

Fragomen took the top spot on this year's scorecard, which double-counts partners to emphasize the importance of promoting minority attorneys, with 32.5 percent of its attorneys identifying as racial minorities. Even then, the firm reported zero black partners. White & Case came in second, reporting 33.2 percent minority representation. Only 29 of the firm's 788 attorneys are black, or 3.7 percent, and only three of those are partners.

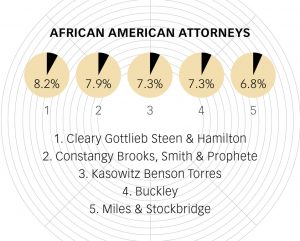

Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton (8.2 percent); Constangy Brooks, Smith & Prophete (7.9 percent); and Kasowitz Benson Torres (7.3 percent) reported the highest proportion of black attorneys. Interestingly, none of those firms took the top spots when isolating for black partnership levels. Butler Snow and Phelps Dunbar reported the highest rate of black representation among their partnership at 5.4 percent each.

Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton (8.2 percent); Constangy Brooks, Smith & Prophete (7.9 percent); and Kasowitz Benson Torres (7.3 percent) reported the highest proportion of black attorneys. Interestingly, none of those firms took the top spots when isolating for black partnership levels. Butler Snow and Phelps Dunbar reported the highest rate of black representation among their partnership at 5.4 percent each.

For comparison, Fenwick & West reported the highest proportion of Asian Americans. More than 23 percent of the firm's attorneys are of Asian descent. Florida-based Cole, Scott & Kissane employs 93 Hispanic attorneys to lead the way at 21.5 percent.

Diversity professionals and black attorneys point to a variety of reasons for the discrepancy, ranging from inequities at the law school level to cultural repercussions born out of the historical African American experience in the United States.

Michelle Silverthorn, founder and CEO of diversity consulting firm Inclusion Nation, points to the lack of black law students present in the go-to schools for associate hiring.

Michelle Silverthorn, founder and CEO of Inclusion Nation

Michelle Silverthorn, founder and CEO of Inclusion NationAs with Big Law, black students often see less overall representation in top law schools compared with other minority groups. Black students account for 7.4 percent of the 2018 student body among the law schools most popular within the Am Law 200: Harvard, Georgetown, New York, Columbia and the University of Virginia, according to American Bar Association data.

“These law firms are all competing for the same small pool of black students at top colleges,” Silverthorn says. “A lot of this is about debt. Many black students are the first in their family to go to law school. They go to the schools that give them the most money, which most of the time are lower-ranked schools.”

Black students also have a lower chance of being accepted to law schools than their white peers, even with similar scores, according to 2016 data compiled by the Law School Admissions Council. LSAT-heavy admission processes often put black students, who often lack the preparation resources of their white counterparts, at a disadvantage, experts say.

“If you look at the same schools to do all of your hiring, you'll miss the numerous talented black attorneys from lower-ranked schools,” Silverthorn says.

Recruitment is one issue; retention is another. While black lawyers make up 4.4 percent of nonpartner attorneys in the Am Law 200, only 2 percent of partners are black.

B. Delano Jordan, founder of Jordan IP Law.

B. Delano Jordan, founder of Jordan IP Law.B. Delano Jordan is among those who left Big Law before making partner. An intellectual property attorney, Jordan left 800-attorney Alston & Bird a year after arriving as of counsel. It marked the second time he left a firm feeling like his race was a problem. He previously left now-defunct Kenyon & Kenyon, he says, because management was discouraging him from building business. Instead, partners recommended he help rainmakers, with the hope that they would chip off some work for him.

Alston did not respond to a request for comment.

While the tug between supporting partners and developing business plays out for all attorneys, regardless of race, Jordan's experience is that when older rainmakers—disproportionately white and male—retire, they often leave the lion's share of clients to white attorneys.

Without the opportunity to develop business, Jordan feared that he would be relegated to what he calls a “partner in name only,” or “PNO,” as many of his fellow black attorneys had been. He left to start his own firm, Jordan Intellectual Property Law.

“The history, no matter what anybody wants to say, of the African American experience in the U.S. is unparalleled,” Jordan says. “When you take that initial tilt or slant of the playing field and you lay that onto the law firm environment, which some would say is cutthroat, it tilts it even more.”

“The history, no matter what anybody wants to say, of the African American experience in the U.S. is unparalleled,” Jordan says. “When you take that initial tilt or slant of the playing field and you lay that onto the law firm environment, which some would say is cutthroat, it tilts it even more.”

He adds, “I felt like personally there was no way to survive in that environment. I had to start my own firm.”

The slant, he says, affects how much partners trust a black attorney to develop their own business. Bias affects how much risk an attorney can stomach, for fear of having their failures magnified, he says.

“We have to work harder. We have to outperform in order to come out on par,” Jordan says.

Solutions and Skepticism

Aside from recruiting from a wider breadth of schools, law firms could establish mentorship programs beginning from undergraduate and stretching through law school, says Marlon Hill, a partner at Miami firm Hamilton, Miller & Birthisel. Early education is a personal issue for Hill, who emigrated from Jamaica when he was a high school sophomore. He has spent five years organizing a legal study program at the majority black Brownsville Middle School.

Marlon Hill of Hamilton Miller & Birthisel

Marlon Hill of Hamilton Miller & BirthiselHill says that law schools could also create endowments that would advance students of color, with the goal of bringing more black students into the pipeline early. And once a firm recruits a black associate, it must make a conscious effort to ensure that they have the opportunity to fully participate in the firm.

“The real meaning of long-term professional success is the opportunity to speak at conferences, holding leadership positions and interacting with clients,” Hill says. “It's not just about compensation, but an opportunity to lead and influence the firm's direction. The opportunity to craft your own destiny professionally is something you cannot put a price on.” Clients add another dimension in the push for diversity. In January, 170 general counsel signed an open letter with the mandate that law firms must do better on diversity or risk losing business.

“If they don't continue to invest in these areas, it will ultimately hurt their bottom line,” Michelle Fang, the general counsel at car-sharing company Turo, who spearheaded the letter, told ALM. “These diversity and inclusion efforts have a good return on investment. It will bring them more clients, more talented lawyers and more cases.”

As clients continue to steer and shape the behavior of law firms, a demand from over 170 companies sends a signal to law firms that diversity will start to affect their bottom lines. Reactions to the letter can be characterized by a mix of optimism and skepticism.

Don Prophete, a partner at Constangy Brooks, Smith & Prophete, is doubtful of the letter's efficacy. He notes that the January iteration is the latest of several open letters that stretch back to the 1990s. The incremental progress in this decade is proof that the proclamations have no teeth, he says.

Don Prophete of Constangy Brooks, Smith & Prophete

Don Prophete of Constangy Brooks, Smith & Prophete“The letters aren't useful; they're incendiary,” Prophete says. “There is this knowing practice of sending these letters with the understanding that there's nothing coming from them. The feedback I've gotten from racially diverse partners and lawyers from across the country is, 'We feel the same way.'”

Joel Stern, CEO of the National Association of Minority and Women Owned Law Firms, takes a check-but-verify approach. He says he's optimistic about the letter. Several members told him that they're working with some of the letter's signatories. Looking forward, Stern wants the companies to be held accountable.

“The key to making this call to action different is to translate it into documentable work streams,” Stern says. “We need to get those GCs to report back. We need to make this version better, sustainable and constant, rather than a wave.”

Email: [email protected]

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Sullivan & Cromwell Signals 5-Day RTO Expectation as Law Firms Remain Split on Optimal Attendance

Eversheds Sutherland Adds Hunton Andrews Energy Lawyer With Cross-Border Experience

3 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Stevens & Lee Names New Delaware Shareholder

- 2U.S. Supreme Court Denies Trump Effort to Halt Sentencing

- 3From CLO to President: Kevin Boon Takes the Helm at Mysten Labs

- 4How Law Schools Fared on California's July 2024 Bar Exam

- 5'Discordant Dots': Why Phila. Zantac Judge Rejected Bid for His Recusal

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250