On the Path to Pro Bono Success, Law Firms Have Plenty to Navigate

From mergers and global growth to the specter of politics, firms developing pro bono programs have challenges to overcome.

June 26, 2019 at 05:30 AM

10 minute read

Credit: Alison Seiffer

Credit: Alison Seiffer

When Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough acquired 150-lawyer Broad and Cassel in 2018, the two East Coast firms had many things in common, but their pro bono programs were vastly different.

Nelson Mullins, based in Columbia, South Carolina, maintained an organized system for pro bono opportunities and tracking, while Miami-based Broad and Cassel encouraged pro bono but didn't track hours the same way. The difference led to a revamp of Nelson Mullins' pro bono system.

“They had a good history of doing good work but didn't track it. For us, it was figuring out how to collect the information of what Broad and Cassel was really doing,” says Erik Norton, a partner in Columbia who was head of Nelson Mullins' pro bono committee at the time of the deal.

Mismatched pro bono programs are one hurdle firms encounter following a merger or large acquisition, alongside the more predictable challenges of matching technology and compensation systems. U.S. firms expanding internationally face similar rocky terrain, since pro bono may be tracked and identified differently outside the United States.

Nelson Mullins isn't alone. Other firms involved in recent mergers had to figure out how to mesh their pro bono programs. A well-established and structured pro bono program makes it easier for firms to track hours and for lawyers to identify work that fits their skill sets. That structure can also lead to more lawyers doing pro bono, resulting in higher overall hours.

Jenner & Block was again the top large firm for U.S. pro bono work in 2018, according to The American Lawyer's annual Pro Bono Survey, with lawyers at the firm averaging nearly 170 pro bono hours, and every lawyer handling at least 20 hours. For international work, Morgan, Lewis & Bockius topped the list, with its lawyers outside the United States handling 47 pro bono hours on average and 95% of them working at least 20 hours.

Overall, the U.S. firms that submitted information for the survey did a little less pro bono work in the United States and internationally in 2018 than in 2017, handling 5.3 million hours, down from 5.4 million hours the year before.

Overall, the U.S. firms that submitted information for the survey did a little less pro bono work in the United States and internationally in 2018 than in 2017, handling 5.3 million hours, down from 5.4 million hours the year before.

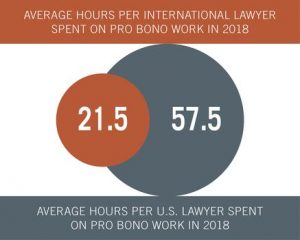

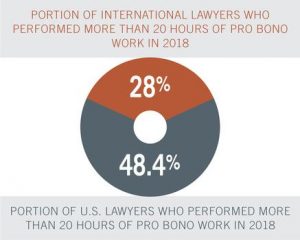

In 2018, 48.4% of U.S. lawyers at the 137 firms that participated in the survey did more than 20 hours of pro bono work, down slightly from a 49.5% average in the 2017 survey. U.S. lawyers at surveyed firms averaged 57.5 hours in 2018, down from 59.7 hours in 2017.

Meanwhile, the numbers improved internationally, Overseas, lawyers at U.S. firms averaged 21.5 hours of pro bono work in 2018, and 28% put in at least 20 hours, according to the survey. That compares to an average of 20.6 hours in 2017 and 26.4% of lawyers doing at least 20 hours.

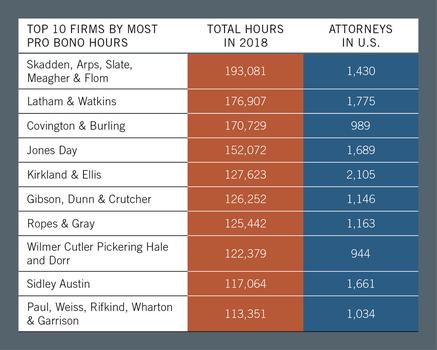

Many of the same firms returned to the top 10 spots on the list for their domestic pro bono work. Covington & Burling, Patterson Belknap Webb & Tyler and Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe all made the top five again, along with Jenner. They were joined by Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr. Paul Hastings, Dechert and Ropes & Gray kept their top 10 status, joined by Hughes Hubbard & Reed and Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom. Buckley (13th) and Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher (18th) slipped out of the top 10.

On the international side, Morgan Lewis topped the list, followed by Dechert, which led the ranking last year. The rest of the top 10 included Jenner; Orrick; Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer; Skadden; Winston & Strawn; Paul Hastings; Latham & Watkins; and Kelley Drye & Warren. Winston & Strawn and Kelley Drye are new to the top 10. Cozen O'Connor (40th) and Gibson Dunn (15th) dropped out of the top tier.

On the international side, Morgan Lewis topped the list, followed by Dechert, which led the ranking last year. The rest of the top 10 included Jenner; Orrick; Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer; Skadden; Winston & Strawn; Paul Hastings; Latham & Watkins; and Kelley Drye & Warren. Winston & Strawn and Kelley Drye are new to the top 10. Cozen O'Connor (40th) and Gibson Dunn (15th) dropped out of the top tier.

Shearman & Sterling, Jenner, and Winston & Strawn each reported that more than 100% of their lawyers did at least 20 hours of pro bono in 2018, a circumstance created by departures. Covington & Burling had the highest average (172.6 hours) in 2018, followed by Jenner (169.7), and Patterson Belknap (148.1).

Pro bono hours count toward associates' billable-hour requirements for 92% of domestic lawyers and 90% of international lawyers at U.S. firms.

The Pro Bono Survey evaluates the Am Law 200's commitment to pro bono work, ranking firms on a metric that incorporates the average number of pro bono hours worked by each of their lawyers and the percentage of lawyers at each firm who spent at least 20 hours on pro bono work in a given year. The U.S. pro bono rankings are for work done by lawyers in the United States, while international rankings are for pro bono work by lawyers at U.S. firms who are based in offices outside the country.

While firms in the survey described a wide range of pro bono initiatives, including civil, criminal and corporate matters, many prioritized immigration issues in 2018, including asylum cases and the representation of children and adults separated at the U.S.-Mexico border. The deep commitment to immigration issues across the spectrum suggests that U.S. firms are setting aside politics when doing pro bono.

While firms in the survey described a wide range of pro bono initiatives, including civil, criminal and corporate matters, many prioritized immigration issues in 2018, including asylum cases and the representation of children and adults separated at the U.S.-Mexico border. The deep commitment to immigration issues across the spectrum suggests that U.S. firms are setting aside politics when doing pro bono.

Andrew Vail, who chairs Jenner's pro bono committee in Chicago, says his firm doesn't think of pro bono work in terms of politics, but instead in terms of providing legal representation to those who don't have access to it.

“Our commitment to pro bono has continued over decades in various administrations. We were one of the first law firms to join the fight against the detention of prisoners at Guantanamo Bay under previous administrations,” he says. “We've been doing asylum work for many years and continue to do that today.”

The politics of pro bono work is rarely an issue at Morgan Lewis, Rachel Strong, the firm's senior pro bono counsel, says.

“Every firm is aware of these issues,” she says. “We are a big tent with a lot of different viewpoints and perspectives, and we want to honor everyone's.”

Removing Roadblocks

While melding pro bono programs can be a challenge for firms going through a merger or expanding into a new market, disparate pro bono programs would probably not directly prevent a combination, consultant Peter Zeughauser of Zeughauser Group says.

“In the scheme of things, it's not at the top of the list,” he says.

But Zeughauser notes that an institutionalized pro bono program is in some ways a litmus test of a firm's culture, and “usually firms don't merge if they aren't culturally well-suited.”

Instead of creating a roadblock to a smooth combination, Norton, the Nelson Mullins partner, says the acquisition of Broad and Cassel led his firm to reboot its pro bono program with the goal of increasing involvement across the firm.

“We treated it almost as if it were a separate division within the merger, where we had to collapse the two programs [together] for purposes of tracking,” he says.

Nelson Mullins tracked hours and associates got credit for them, while Broad and Cassel didn't differentiate between pro bono work and community service but expected its associates to “do good works,” Norton says. Under the new system, which was presented to lawyers at a firm retreat in May, lawyers now get credit for every pro bono hour instead of going without credit for the first 20, he says, a requirement the firm adopted years ago to set an example in the market.

Nelson Mullins tracked hours and associates got credit for them, while Broad and Cassel didn't differentiate between pro bono work and community service but expected its associates to “do good works,” Norton says. Under the new system, which was presented to lawyers at a firm retreat in May, lawyers now get credit for every pro bono hour instead of going without credit for the first 20, he says, a requirement the firm adopted years ago to set an example in the market.

The distraction of the massive acquisition didn't affect the firm's overall pro bono hours, but fewer lawyers participated in 2018, which Norton attributes to lawyers being pulled in different directions. The revised program should improve hours going forward, particularly as legacy Broad and Cassel lawyers get accustomed to the system, he says.

Nelson Mullins wasn't alone in blending pro bono programs during a merger last year. Virginia-based Hunton & Williams merged with Texas-based Andrews Kurth Kenyon. Mitch Reid, a co-chairman of the Houston office's pro bono committee, says the firms had very similar, well-established pro bono programs, so combining them wasn't difficult.

“The two legacy firms got together very early on and discussed the best practices of each side,” Reid says. “What we took away was we were doing really great things in the communities we served.”

Hunton Andrews Kurth's pro bono program now offers more training for lawyers, Reid says. Its pro bono contribution didn't slip during the hectic merger year. Reid says Hunton & Williams had obtained 100% participation for the last decade, while Andrews Kurth didn't track hours despite a big commitment. The combined firm, he notes, hit the 100% mark.

“Each firm had a very robust pro bono program and a lot of people committed to pro bono,” he says. “To be able to do this right out of the box has been very easy.”

Ellen Bonacorsi, senior counsel at Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner in St. Louis and chairwoman of the firm's pro bono committee, says the firm is still working to combine the pro bono programs in place at the time of the 2018 merger of Bryan Cave and the U.K.'s Berwin Leighton Paisner. But she says the movement toward a unified policy has been smoothed by each firm's strong commitment to pro bono and tracking hours.

The fast-growing Morgan Lewis picked up about 750 lawyers and staff in 2014 from Bingham McCutchen, and in the same year merged with the 80-lawyer Stamford in Singapore. According to Strong, Morgan Lewis and Bingham had very similar pro bono cultures, and meshed well.

“It could potentially be harder with non-U.S. offices, but we've been really lucky,” she says, adding that the firm expects every lawyer to bill 20 or more pro bono hours and new lawyers are not given leeway on that requirement. That bar was met last year by 95% of the firm's lawyers.

Strong says international offices in Moscow and London are among the most active for pro bono. With a window into the range of pro bono work because of her responsibility approving pro bono matters, she says lawyers in Moscow generate all of their own pro bono work, and the level is high in London as well.

“Both had very strong cultures,” Strong says. “There were light differences in the kind of work, but not whether or not they were doing the work.”

Detroit's Clark Hill and Dallas firm Strasbuger & Price, which combined in 2018, also dealt with some small differences after they merged. But Gregory Longworth, a senior attorney in Grand Rapids, Michigan, who chairs the pro bono committee, says none of it presented a barrier to joining the two pro bono programs. He says associates and senior attorneys can earn credit for up to 50 pro bono hours a year.

Much of Clark Hill's pro bono work is identified through practice groups, Longworth says, and the immigration practice group in particular has been active, handling asylum work and other immigration matters in Texas, an area that was popular in 2018 among firms that participated in the survey.

The effort of Clark Hill's immigration practice group to step up and do pro bono work in Texas is an example of lawyers across the firm working together, Longworth says.

“That's the type of thing that has melded fast,” he says.

Email: [email protected]

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

White & Case Crosses $4M in PEP, $3B in Revenue in 'Breakthrough Year'

6 minute read

Haynes and Boone Expands in New York With 7-Lawyer Seward & Kissel Fund Finance, Securitization Team

3 minute read

'None of Us Like It': How Expedited Summer Associate Recruiting Affects Law Students and the Firms Hiring Them

Sheppard Mullin, Morgan Lewis and Baker Botts Add Partners in Houston

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1TikTok Opts Not to Take Section 230 Immunity Fight to U.S. Supreme Court

- 2Feasting, Pledging, and Wagering, Philly Attorneys Prepare for Super Bowl

- 3Special Section: 2025 Real Estate Trends

- 4Snap Paid $63M in Fees to 2 Am Law 200 Firms in '24

- 5Lawyers Across Political Spectrum Launch Public Interest Team to Litigate Against Antisemitism

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250