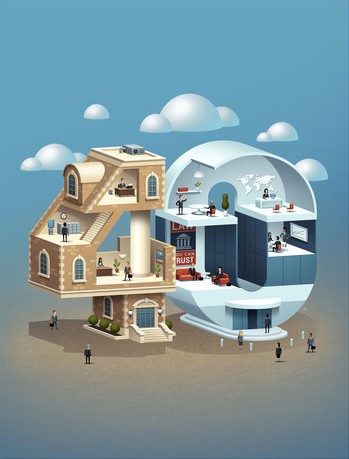

Industrial Evolution: How Big Law Blossomed Over the Past 40 Years

Since The American Lawyer was founded in 1979, we've tracked the legal profession as it turned into an industry.

September 03, 2019 at 05:30 AM

18 minute read

Credit: Chris Morel.

Credit: Chris Morel.

Shortly after Sheila Birnbaum joined Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom in 1980 as the firm's 185th lawyer, Joseph Flom told her and a room full of partners they would one day grow to 1,000 lawyers. At the time, it seemed impossible.

"We all looked at him like he lost his mind," Birnbaum says.

But Flom, as she and others often say, was a visionary. He had worked for years to entice Birnbaum to leave teaching to launch a products liability practice at the firm. Most other large firms viewed products liability as low-end insurance defense work, but Flom saw something more. Major corporations were starting to become self-insured and they wanted their trusted advisers by their side when major litigation hit.

Through moves like that, Flom eventually made good on his promise to grow Skadden. It evolved from a New York shop to an international powerhouse. Dozens of firms have since surpassed the once-unthinkable 1,000-lawyer milestone.

The industry's national and then global expansion coincided with—and, in some ways, was fueled by—the birth of The American Lawyer. Flom had a hand in that, too. A few years before launching the magazine, Steven Brill was captivated by the personal stories of Flom and another trendsetting lawyer, Martin Lipton, planting the seed that grew into this publication.

Brill, who was writing an occasional column for New York Magazine while at Yale Law School, was getting a snack from the vending machines on campus when he noticed that the career placement center's recruiting board was covered in letters from large law firms all saying the same thing: They were unique, their clients were unique and they wanted unique associates to come work with them. (Sound familiar?) Brill figured he'd give writing about the law a shot and went looking for a story.

Credit: Jonathan Reinfurt

Credit: Jonathan ReinfurtPublished in New York Magazine in 1976, the resulting piece profiled two Jewish lawyers who couldn't get jobs at Wall Street firms and eventually started their own shops—Flom at Skadden and Lipton at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz. Flom and Lipton also happened to be revolutionizing the deal world, handling lucrative takeover and tender-offer fights. And by the early '80s, Lipton would create the poison-pill defense. Lawyers and investment bankers were now operating in the same boardrooms, and young associates grew envious of their newly well-heeled colleagues' pay. Brill had more stories to tell.

After the piece on Lipton and Flom came out, Brill followed an editor to Esquire and started writing regularly on the business of law. He launched the magazine in 1979, two years after the U.S. Supreme Court issued its groundbreaking ruling in Bates v. State Bar of Arizona, which upheld lawyers' right to advertise. Attorneys could no longer hide behind ethics rules to avoid a reporter's calls. Well, at least theoretically.

"I ended up cold-calling a lot of managing partners at hoity-toity firms and some of them would tell me the questions I was asking were illegal," Jill Abramson, the former New York Times executive editor who helped launch the magazine and spent 10 years reporting for it, says of the early days. "A lot of people just hung up on me. It was stressful."

Lawyers didn't want to talk about compensation, disclose who was on their management committee or dare name their clients. Abramson and other reporters often relied on printed editions of Martindale-Hubbell for pieces of information.

But Brill put the magazine in the hands of the right people to gain influence. David Boies remembers attending a bridge tournament where the magazine sat in stacks for the taking. The publication both reflected the industry and accelerated its progression, Boies says.

Brill had reporters stay in posh hotels when they were on assignment, Abramson recalls. He wanted lawyers to take the reporters and the magazine seriously. But it took a few years to get there.

"In the beginning, the first year or two, I would say half the people you got on the phone would hang up on you immediately," Brill recounts. "It was just time, a war of attrition"—and reporting valuable information—that gave the magazine staying power.

It didn't come without a personal cost for Brill and his family. His wife, Cynthia, was an attorney with what was then Winthrop, Stimson, Putnam & Roberts in New York. A few of the partners called her and Brill in for a meeting in the library of the Yale Club. They couldn't have someone at the firm who was associated with Brill, they said. She offered to use her maiden name, but that wasn't good enough.

Steve Brill, co-founder of The American Lawyer. Credit: David Handschuh/ALM.

Steve Brill, co-founder of The American Lawyer. Credit: David Handschuh/ALM.The industry has certainly softened to the existence of the magazine, but not everyone has gotten over the fact that partner compensation is more than water cooler talk. Lipton, who encouraged Brill to start the magazine, says he may have reconsidered had he known that revenue and profit rankings would soon follow.

"If I had known that it was going to focus on the economics of law firms and make public estimates as to how firms were doing, I never would have been in favor of it," Lipton says. "That has been, I won't say a disservice, but certainly it has not been helpful to the legal profession, and I think it has focused the legal profession on the wrong things. It is, in part, what stimulated the creation of the mega firms."

Brill, who laughs when he hears Lipton's comments, is familiar with being blamed for helping take collegiality out of the profession. And he recognizes there is always some risk when it comes to what is done with information once it becomes available. But, as a journalist to his core, he cares more about transparency.

"It's one thing to say, 'Gee, we always used to be collegial,'" Brill says. "Yeah, but you also didn't have women or Jews, and didn't have to worry about competition because you all overbilled your clients because the GC was a friend."

What's Old Is New Again

Despite monumental changes in the legal industry, much has stayed the same. Headlines from the early days of the magazine could easily be confused with those written this year. Hot topics at the start included partner compensation, diversity and gender struggles, strategic planning, the hiring of business professionals, marketing and business development, mergers, lateral hiring and, of course, the billable hour.

Skadden; Wachtell; Cravath, Swaine & Moore and their ilk were frequent subjects from the jump. The first edition, in February 1979, detailed a PricewaterhouseCoopers report on law firm financials, in which Skadden was the highest-grossing firm. That was six years before the Am Law 50 first published in 1985 and many years before it became acceptable to discuss law firm compensation in civilized circles.

The preview issue of The American Lawyer, published August 11, 1978. Credit: David Handschuh/ALM.

The preview issue of The American Lawyer, published August 11, 1978. Credit: David Handschuh/ALM.But it wasn't just the Wall Street elite that graced the magazine's pages. A Chicago-based shop called Kirkland & Ellis was on the cover of a 1978 preview edition, reportedly "under siege" after a fired partner tried to take lawyers and clients with him. In July 1987, another story about Kirkland, "Winners Without a Leader," suggested it was poised for success but lacked a unifying leader. Fred Bartlit was identified as one of many leaders, but by 1993 he left to start one of Big Law's first litigation boutique spinoffs, Bartlit Beck—a trend with many high-profile copycats, such as Boies leaving Cravath in 1997 to start what is now Boies Schiller Flexner or Beth Wilkinson leaving Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison to start Wilkinson Walsh Eskovitz in 2016.

Both Kirkland and Bartlit Beck, as it turned out, became wildly successful. They illustrate two of the paths many firms were beginning to take. A select few chose to stay lean and local; many others started expanding.

The Great Transformation

As Jim Jones, director of the Program on Trends in Law Practice at the Georgetown Law Center on Ethics in the Legal Profession, notes, the story of the last 40 years is about the rise of competition among law firms. It can be seen in the flood of lateral movement, the expansion of firms and the rise of mergers, specialization, star salaries and increasing client power. Those in the industry debate the causes, though many cite both the spread of technology and the availability of information. Along the way, more incremental factors contributed to the evolution of the large law firm.

In the late '70s, firms were almost always in one market, where their clients were. When they couldn't handle a clients' needs, they found lawyers elsewhere who could help. It was a national referral network, and almost every firm in the country would have fit into today's "independent" model. There was something like a gentlemen's agreement that firms wouldn't open up shop in another city.

The first issue of The American Lawyer, published in February 1979. Credit: David Handschuh/ALM.

The first issue of The American Lawyer, published in February 1979. Credit: David Handschuh/ALM.As states loosened restrictions about who could practice in a given jurisdiction, firms thought harder about opening a California office or expanding into Washington, D.C., longtime consultant Brad Hildebrandt says. Couple that with growing demand for legal services in the '70s and '80s, former Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe chairman Ralph Baxter says, and firms saw reason to ramp up lawyer hiring, in their home bases and beyond.

"Slowly, over time, they started to grow into each other's backyards," says William Henderson, who teaches a course on the legal profession at the Indiana University Maurer School of Law. The number of lawyers didn't rise in each market, but the firms competing for work did, leading to "a huge disruption in market power."

Of course, none of that could happen if lawyers weren't willing to move in the first place. The American Lawyer certainly had a role in kickstarting the lateral market. In the late '70s and early '80s, it was "unseemly" to make a lateral move, Hildebrandt says. But the magazine started highlighting law firm operations at the outset, and began publishing partner compensation with the Am Law 50 in 1985. The Am Law 75 followed a year later and the Am Law 100 a year after that.

After the first Am Law 50 published, Brill got a call from a law school classmate working at O'Melveny & Myers. He was happily making a six-figure income but saw that a fellow classmate at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher was making $100,000 more. He and his wife wanted to know why.

Even before public reports of firm financials, there were phenomena like associates working side-by-side with investment bankers or Cravath doubling starting salaries in the late '60s from $7,500 to $15,000, Boies notes. That move started the "tiering" of law firms, he says. Firms in major cities were all paying top dollar, but Cravath knew not everyone could follow its big step forward.

"This began a cycle where law firms were really competing with money to attract associates," Boies says, after years of competing on "lifestyle, practice and chance of being a partner."

By 1979, The National Law Journal (not yet an affiliate of The American Lawyer) reported that the highest first-year associate starting salary was $31,500, at Finley, Kumble, Wagner, Heine, Underberg, Manley, Myerson & Casey. (Lengthy law firm names also disappeared in the last 40 years.)

Finley Kumble went into bankruptcy in 1988, a spectacular demise for a law firm, the likes of which hadn't been seen. A 1987 article in The American Lawyer, "Bye, Bye Finley Kumble," predicted the firm's collapse. Almost a decade into the publication's existence, Brill says it was a moment that helped solidify the magazine's deep understanding of the industry.

Finley Kumble's story will sound familiar to those who followed more closely the demise of Dewey & LeBoeuf. The firm offered up guarantees, took in a lot of capital and grew quickly, but also had amassed $76 million in debt upon its collapse. Financial reporting was shaky at best. The firm's true fiscal health and business practices were laid bare upon its dissolution.

Several more storied firms disappeared over the ensuing decades, but the dominant story was the industry's meteoric growth.

"Corporations went global in a big way and they took law firms right along with them," Jones says.

Bob Dell, a longtime leader of Latham & Watkins who joined the Los Angeles-founded firm's fledgling Chicago office when it opened in 1982, tells a story emblematic of so many of the nation's largest law firms.

When he joined Latham, Coudert Brothers and Baker McKenzie were the only true international firms. Latham took the bold step of opening a New York office in the mid-'80s and its success gave the firm the confidence to enter other major markets, including Dell opening a San Francisco office in 1990. At a 1999 executive committee meeting, Latham's leaders realized the firm was at a crossroads. It could continue expansion into lower-tier U.S. cities or go international.

"There was a real question whether we could succeed in that," Dell says of the international plan. But the firm had already made a bet on core industries, particularly investment banking and private equity, and those clients weren't in cities like Atlanta.

Latham didn't want to be a franchise operation with a few lawyers in a lot of locations, and it didn't want to mess with its culture. After some advice from McKinsey, the firm felt it could succeed by competing at the highest level in its core industries, thanks in part to its practice mix and culture.

Latham, now the second-largest firm in the world with more than $3 billion in revenue, became a marvel in the industry that many other firm leaders say has staying power. Dell credits the rise of the private equity industry as a factor in the firm's success. Before the industry was established, even loyal clients would turn to Skadden or Wachtell for their biggest M&A deals, work that only a handful of firms handled. When private equity came along, "there was an opening for firms like us," Dell says.

At the opposite extreme, pure M&A and an old-school business model have helped Wachtell stay elite to this day. The firm was created on a handshake and remains without a partnership agreement, Lipton says. In a way, it was an early adopter of the alternative fee model, known for telling clients to name a price if they don't like a proposed fee. As other firms grew, Wachtell kept its one-office policy and lockstep compensation, operating as the "antithesis" of the global firms, Lipton says. But he recognizes the firm is an outlier.

"I don't think you can turn back," Lipton says of the growth of law firms. "Global expansion is the future."

Clients and the Day-to-Day

Making clients happy is a relatively new phenomenon. Lawyers have always had to be excellent, but they once called the shots. General counsel didn't exist in the late '70s in any meaningful way, so outside counsel were making the big decisions on who to hire (surprise, themselves) and they knew every aspect of a client's business. Whether because in-house legal departments had more access to information about the industry or simply followed the growth of their broader corporations, they became more commonplace over the years.

"The profession was dominated by the senior partners of the major law firms in the big cities," Lipton says. "Today, the profession is dominated by the general counsel of the public corporations."

Jami Wintz McKeon, now the chair of Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, says the lawyer-client relationship has changed since she was a new associate in 1981, in part because firms were smaller and most of the critical modern technology didn't exist. Everyone was involved in clients' day-to-day business, regardless of title. But as in-house teams grew, clients took on more work themselves, calling on law firms only when they faced complicated problems. The work is more interesting and less rate-sensitive, but firms don't get to know the ins and outs of their clients the way they once did, McKeon says.

"It was a closer relationship," Hildebrandt says, one defined by a business mentality. But it may not have been as good for clients, many argue.

"Many law firms were very, very sleepy," Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher's Ted Olson says. "Every client was never going anywhere else"—until they were made aware, by the magazine and others, that they had options.

The Great Recession of 2008 brought grand reports of clients being placed firmly in the driver's seat, mounting pressure on law firms to compete with one another and alternative providers. While clients are in control, change wasn't necessarily as dramatic as predicted.

Aric Press, who took over as editor-in-chief of The American Lawyer in 1998 after Bruce Wasserstein bought the magazine, now spends his time speaking with clients on behalf of law firms. Clients don't ask for fundamental changes in how their outside counsel operate, he says. Instead, they still want law firms to help solve their toughest problems.

What has changed, he and others suggest, is the daily life of an associate or partner. Partners are billing 2,500 hours a year at some Big Law firms, Press says. And associates are working just as hard as they did decades ago, but the illusion of guaranteed partnership isn't there anymore. Firms don't even pretend, he says.

"How do you manage a workforce where the employees are being asked to work extremely hard but they know, from both sides, that there probably isn't a future for them?" Press asks.

Impact on the Practice of Law

The business of law isn't the only thing to evolve over the past 40 years. While law firms today are commonly stereotyped as woeful when it comes to business innovation, lawyers have always been innovative in the way they solve clients' legal problems. Whether it be Lipton's poison pill or novel arguments for the legalization of same-sex marriage, substantive areas of the law have evolved from the beginning of the modern American legal system. Most of that was driven by pure legal ingenuity, but it had a little help from technological advances and the flow of information.

Take Olson's career trajectory. He became a household name leading litigation on same-sex marriage, Bush v. Gore, campaign finance, sports betting and more. He and others became celebrities through coverage of their work, whether it was in The American Lawyer or the Washington Post.

"Lawyers always said if they were contacted by a reporter it was like opening the door and seeing a poisonous snake there, and they would always say 'no comment,'" Olson recalls. "Now we understand we have to deal with public opinion."

And the legal marketing industry, spurred by the Bates decision but highly refined in the 42 years since, ensures firms not only deal with the press, but seek out coverage.

The combination of a more robust flow of information and technological advancements helped form a practice that didn't exist when Birnbaum started practicing products liability law.

"I still remember when we had one plaintiff, one defendant and one judge and we went to court," Birnbaum says.

There were none of the multidistrict litigations or class actions she so commonly handles now. Mass torts couldn't have existed when carbon copy paper was still a thing. How would lawyers file all those complaints and responses? Add to it the ability for plaintiffs lawyers to advertise, computers to connect offices and the courts updating federal procedural rules, and a mass torts practice was born.

The birth of The American Lawyer took a lot less time. In seeing the success of his early columns, Brill wondered why there were publications dedicated to the business of fashion, automobiles or entertainment, but not law. That was his pitch. Within 45 minutes of putting it to British conglomerate Associated Newspapers Ltd., he convinced his financial backers that the world needed a publication like The American Lawyer.

"It spoiled me forever," Brill, a serial entrepreneur, says. It was relatively easy to get millions in funding—ultimately $35 million—to launch the publication. It was a 45-minute pitch that changed the trajectory of Big Law. In fact, it made Big Law.

"There was before The American Lawyer," Boies says, "and after The American Lawyer."

Email: [email protected].

Ben Seal contributed to this report.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Greenberg Traurig Litigation Co-Chair Returning After Three Years as US Attorney

3 minute read

Blank Rome Snags Two Labor and Employment Partners From Stevens & Lee

4 minute read

12-Partner Team 'Surprises' Atlanta Firm’s Leaders With Exit to Launch New Reed Smith Office

4 minute read

After Breakaway From FisherBroyles, Pierson Ferdinand Bills $75M in First Year

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Settlement Allows Spouses of U.S. Citizens to Reopen Removal Proceedings

- 2CFPB Resolves Flurry of Enforcement Actions in Biden's Final Week

- 3Judge Orders SoCal Edison to Preserve Evidence Relating to Los Angeles Wildfires

- 4Legal Community Luminaries Honored at New York State Bar Association’s Annual Meeting

- 5The Week in Data Jan. 21: A Look at Legal Industry Trends by the Numbers

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250