The Trend to Watch: Forecasting the Future Direction of the Legal Market

In-sourcing and other client-side trends have dominated the conversation in the legal market over the past decade. One trend suggests the future will look slightly different.

September 18, 2019 at 03:41 PM

10 minute read

The most important legal market trends of the past decade have been related to changes in client sourcing and buying patterns. Chief among those trends is the decision of general counsel to in-source legal work. Make no mistake, technological changes have been important, as has the rise of the alternative service provider. That said, when the data is analyzed, one can make a fairly convincing case\ that these important changes pale in comparison to the in-sourcing trend.

Skeptics of this argument should look no further than a 2017 Altman Weil survey of law firm managing partners. When asked to identify who their firm was losing market share to, 82% cited their own clients' in-house teams. In-sourcing, it turns out, has been the most powerful force of disruption in the legal industry over the past decade.

What is the future of in-sourcing and other client-side trends? That is the billion-dollar question. Its answer will likely decide the direction the legal market takes over the next decade. At first glance, it might look as if current levels of in-sourcing will continue or perhaps even increase. The logic underpinning in-sourcing—that hiring an in-house resource is cheaper than hiring a law firm lawyer—is as true today as it ever was. A wider analysis, focusing on the root causes driving general counsel toward in-sourcing, tells a different story. It suggests the forces driving this powerful and disruptive trend may be waning. If that forecast is accurate, the legal market may have significantly more change coming.

The Trend's Importance

The logic that drove the in-sourcing trend is fairly straightforward. The cost of hiring a law firm lawyer was, and still is, significantly higher than an in-house lawyer. At present, the cost of hiring an in-house counsel, including compensation and benefits, averages $280,000. Meanwhile, a law firm lawyer in the United States averages $840,000 per year. That is three times the cost of an in-house resource. Importantly, the gap between these two has increased dramatically over the past several decades. Between 1996 and 2018, the price of hiring a law firm lawyer increased by 131%. This rate of increase is nearly twice the rate of inflation over the same period. This math made the decision to in-source simple.

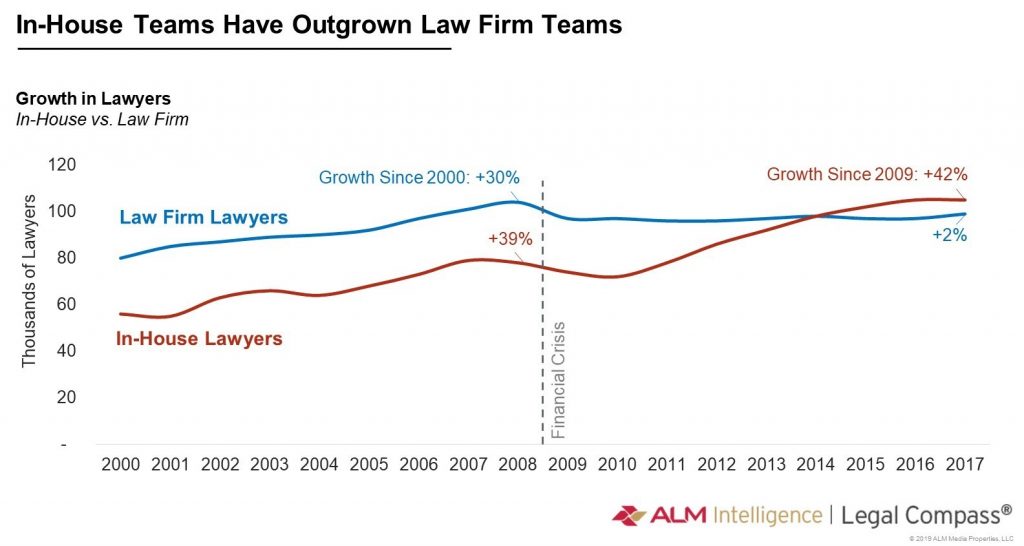

Those doubting the amount of in-sourcing that has occurred over the last decade need only look at the data (another good source on this topic is a 2018 article by Hugh Simons and Gina Passarella). Between 2000 and 2008, head count at law firms and law departments largely moved in tandem. Head counts rose as the economy heated up in the early and mid-2000s and then fell as the financial crisis took hold in 2008. The head count at law firms and law departments rose at similar levels during this period, by 30% and 39%, respectively. Then something changed. Around 2010 the growth of law firm teams flat lined while the growth of in-house teams accelerated. The result of these trends is dramatic. Between 2010 and 2017, in-house teams in the United States added over 30,000 lawyers to their ranks while law firms remained largely static. In total, law departments increased in size by more than 40% in this period while law firm head counts rose by a measly 2%.

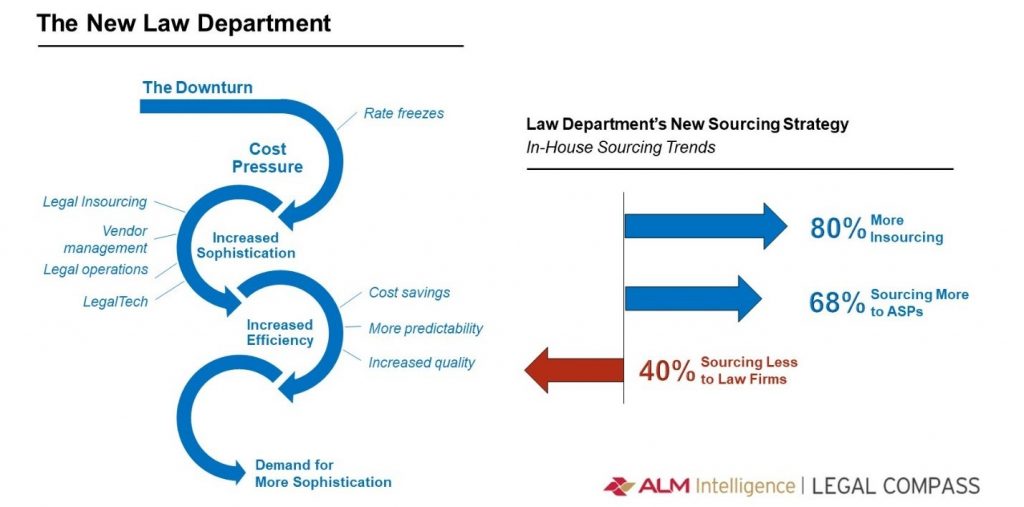

What was the impact of all this in-sourcing? The immediate impact, despite head count additions, was cost savings. These savings whet the appetite for greater change. This ushered in new approaches to pricing, vendor selection, law firm management and the use of technology. The increased complexity created by the new hires led to demand for more resources to help manage operations and strategy. To see the total impact of these forces, all one needs to do is visit the Corporate Legal Operations Consortium's annual conference. On display at that conference is a vast array of new, often bold initiatives to rethink the way law departments deliver legal services to their corporate clients and procure services from legal services vendors.

The impact of in-sourcing on law firms is more a complicated story. Many believed that law department in-sourcing and the CLOC revolution that followed would strain the law firm business model to the point of breaking. That did not happen. Few law firms have failed since the downturn, and there is little evidence to suggest a reckoning is coming. That said, a comprehensive analysis of the data suggests that the fallout from the downturn and the subsequent market changes occurring in its wake have taken a toll.

The most obvious impact of in-sourcing has been a significant decrease in demand growth for law firms. The heady days of the pre-downturn period, where law firms grew by double-digit percentages each year, are over. In their place is a market that exhibits little organic growth. For evidence of this look at the quarterly reports of law firm finances by Citi, Wells Fargo and Thompson Reuters. The Am Law data, published by ALM Intelligence and The American Lawyer, also provides compelling evidence of the slow-growth environment managing partners have had to contend with.

Other impacts of in-sourcing are less obvious, but perhaps more important. As demand growth slowed, most law firms did not immediately alter their hiring strategies. This led to a mismatch in the growth rate of demand and lawyers. Put simply, many law firms had too many lawyers in the period after the downturn. Economists tell us that excess supply puts pressure on pricing. This is exactly what happened to law firms. Collected hourly rates have grown at a snail's pace in the post-downturn period and inflation-adjusted revenue per lawyer is well below the rate that historical trends suggest it should be at.

Stepping back from the individual data points reveals a market profoundly altered by general counsel's decision to in-source legal work. The big question is what happens next.

The Root Cause

At first glance, it would be tempting to believe that the in-sourcing trend will continue to speed up. Many of the forces that led to its rise are still in place today. Law firm lawyers continue to cost several multiples of what in-house resources costs. Their price also continues to grow faster than inflation. Additionally, general counsel have seen the power of in-sourcing and other CLOC-related initiatives and the cost savings they bring. In such a light, it may appear that the in-sourcing trends have just begun. This logic, however, misses an important link in the in-sourcing story.

All things being equal, GCs and their chief financial officer counterparts would rather not add new head count to their organizations. All else, of course, is not equal. Law firms are significantly more expensive. Given this fact—and with virtually no other options—law departments accepted the suboptimal option of in-sourcing. Re-read that last sentence again. Within it is the root cause of in-sourcing. High law firm prices were a driving force that led law departments to in-source. The root cause of this trend, however, was a realistic lack of options.

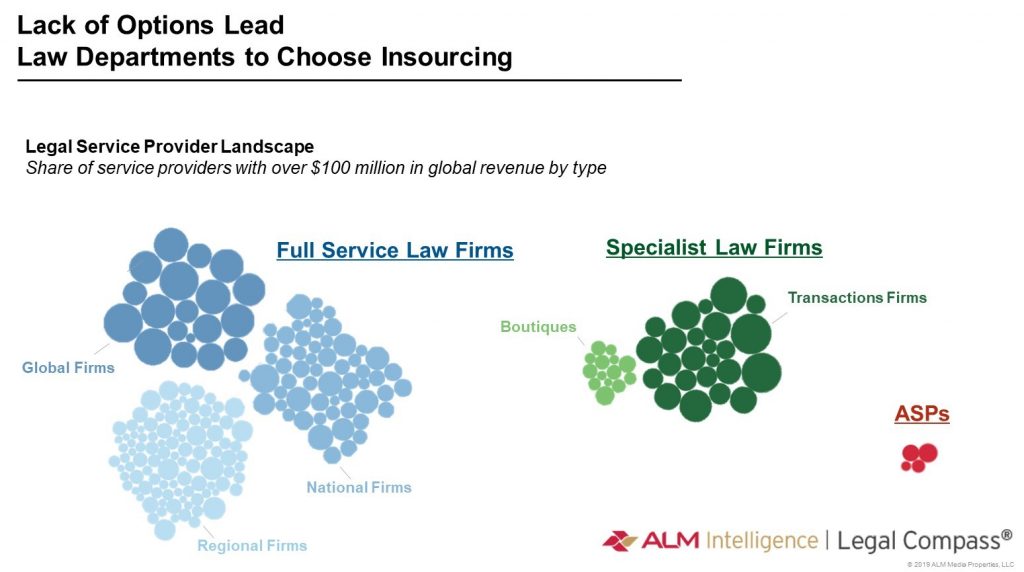

A comprehensive look at the legal industry vendor landscape in the period after the downturn reveals that law firms were, for the most part, law departments' only option aside from in-sourcing. The alternative service provider market had yet to be formed. This is changing rapidly and it is likely to lead to a significant shift in law department sourcing strategies.

There is almost no need to provide evidence for the assertion that the vendor landscape within the legal industry is rapidly evolving. Evidence for this argument is everywhere. On the law firm side there is news of a major merger every few months. There are also plenty of announcements of law firms making major investments in technology or process improvement. Then there is the steady stream of news related to investments in legal tech. The $50 million invested in Kira and the $65 million invested in Atrium are just two recent examples. Then, of course, is the steady stream of acquisitions by alternative service providers. Elevate's acquisitions of LexPredict, Sumati and Halebury are good examples. So are the acquisitions by the Big Four: Deloitte's deal with Berry Appleman & Leiden, PwC's deal with Fragomen, and EY's deals to acquire Riverview and Pangea3. All of these deals are reshaping the vendor ecosystem within the legal industry. Most important, the deals in the legal tech and ALSP space are giving law departments new options. They no longer need to choose between sending work to law firms or doing it themselves. There is now a third way.

The impact of this evolution should not be understated. One of the oddities of law departments' decision to in-source work was that it contradicted one of the dominant corporate trends of the 21st century: outsourcing. Almost every corporate function has moved in the direction of doing less in-house and doing more through outsourcing contracts. This trend began with IT departments in the mid-1990s, but quickly spread to finance, marketing, human resources and almost every other support function within large corporations.

There are good reasons corporations turn to outsourcing. Studies consistently show that outsourcing cuts costs. Equally important are the non-cost-related impacts. Large corporations report that outsourcing allows them to solve capacity issues, enhance service quality, access expertise and increase their focus on core services. What are the market conditions required for corporations to take advantage of these benefits? First and foremost, there must be vendors capable of delivering managed services at scale. Until recently, the legal market could not say it had met that precondition. In many service areas it still can't. But in some areas, ALSPs have built the right capabilities and the range of services they offer continues to expand.

What does the future of the legal market, with an evolved alternative service provider segment, look like? It's difficult to say. The ALSP market is still evolving, after all. That said, the future is likely to look significantly different than the past. The ALSP operational model, which tends to be less reliant on costly lawyers, will be able to deliver services more efficiently. Managed services contracts, which tend to be of longer term than the contracts between law firms and law departments, may allow for new types of delivery models. All of this will change the way law departments approach pricing and sourcing. Notably, it will fundamentally change the math that led law departments to in-source.

Will the rise of alternative service providers spell doom for law firms? Probably not. Law firms are well positioned to keep the high value work they covet most. Many law firms may actually benefit from the rise of alternative service providers and managed services. Partnerships with ALSPs and technology vendors could help midsize law firms to compete on an even keel with the biggest firms. Elite firms may find that partnerships with ALSPs allow them to focus on the highest value work, enabling increases in profitability. All of this is speculative of course. ALSPs have a significant amount of work cut out for them. That said, this space is clearly the one to watch. The evolution of the ALSP segment will, almost certainly, determine the direction the legal market takes over the next decade.

Nicholas Bruch is the global tax analyst team lead at EY.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Ridiculously Busy': Several Law Firms Position Themselves as Go-To Experts on Trump’s Executive Orders

5 minute read

Holland & Knight Hires Former Davis Wright Tremaine Managing Partner in Seattle

3 minute read

Am Law 200 Firms Announce Wave of D.C. Hires in White-Collar, Antitrust, Litigation Practices

3 minute read

Paul Hastings Hires Music Industry Practice Chair From Willkie in Los Angeles

Trending Stories

- 1Inside Track: AI Is Sure to Fray Big Law's Devotion to Billable Hour

- 2Evidence Explained: Prevailing Attorney Outlines Successful Defense in Inmate Death Case

- 3The Week in Data Jan. 24: A Look at Legal Industry Trends by the Numbers

- 4The Use of Psychologists as Coaches/Trial Consultants

- 5Could This Be the Era of Client-Centricity?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250