Lawyer Well-Being at Work: It's a Two-Way Street

It's not the number of hours we're billing or the number of hours we're working; it's the way we feel about how we spend those hours that matters.

December 11, 2019 at 03:00 PM

7 minute read

The original version of this story was published on Law.com

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

When I speak at law firms about enhancing the well-being of their lawyers and professional staff, the vast majority of the people in the audience are interested about the topic and appreciative that their firm is taking an interest in how to help them thrive.

When I speak at law firms about enhancing the well-being of their lawyers and professional staff, the vast majority of the people in the audience are interested about the topic and appreciative that their firm is taking an interest in how to help them thrive.

But lawyers are lawyers—we're skeptics at heart.

So inevitably someone will raise a hand, or grab me during a break, and say something like this: "Thanks for being here, but isn't this just the latest way to try to squeeze more out of me? If you want my well-being to be better, why don't you get rid of the 2,000 billable hour requirement? That would help my well-being."

It's an understandable question. Lawyers work hard, and case loads can feel overwhelming. Working long hours, tracking those hours and feeling that we have to grind all year to hit a specific number of hours to meet a profitability target can make us feel like fungible, dehumanized automatons rather than highly trained providers of specific and thoughtful solutions to complex legal challenges. It all can contribute to burnout—a toxic blend of physical and emotional exhaustion, cynicism and a lack of control or ability to change things.

So yes, billable hours are a drag, and profitability requirements don't do great things for our "chi," what Asian religions call the harmonic life force that connects us to the universe. But most of the time, the long hours aren't really the core issue.

While there are obvious outlier scenarios (no one can work 200, 20-hour days in a row and maintain a consistent level of energy), researchers have found that lawyers who work long hours each week report the same levels of self-satisfaction about their work as lawyers who work considerably fewer hours each week. It's not the number of hours we're billing, or the number of hours we're working; it's the way we feel about how we spend those hours that matters.

When our response to a well-being speaker is a question about whether the firm is trying to squeeze more out of us, the underlying issue may be that the firm is not engaging us in our work.

Engagement is almost the complete opposite of burnout. Where burnout is cynical, exhausted and overwhelmed, engagement is energetic, dedicated and absorbed. Engaged lawyers have a sense of pride in their work and their organization, and puff out their chests a little when they say where they work. They say good things about the organization to colleagues and outsiders, they stay at the firm even if they have offers to leave, and they strive to go the extra mile to help the organization and their colleagues be successful.

Businesses that increase employee engagement have experienced increased sales, better customer service and customer satisfaction, increased revenue and profits, better individual job performance, increased retention and reduced turnover.

It's pretty straightforward, actually. When we are engaged in, and engaged by our work, we'll "say, stay and strive." If not, we'll burn out and leave, and we may ruin a few client and work relationships along the way.

Instead of an Upton Sinclair novel where owners try to squeeze the last drop of sweat for your fungible brow, a smart employer will want you to feel more engaged so that you willingly and happily bring more of your energy to work. That helps both you and your organization.

So how do we help you to feel more engaged?

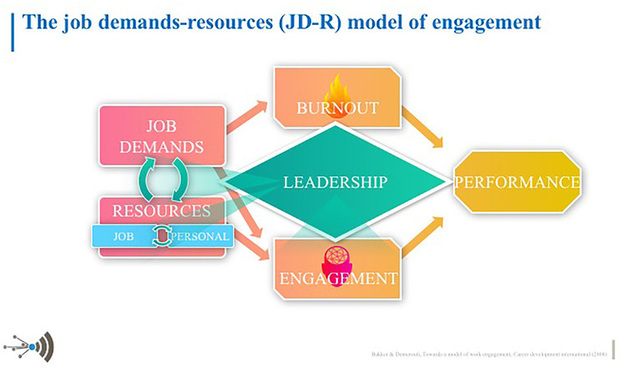

At its core, engagement results from a positive relationship between an individual and an employer. And like any other relationship, it's a two-way street that requires mutual communication, mutual recognition and mutual regard. Psychologists have been studying engagement for decades, and what has emerged is the Job Demands-Resources Model, which looks like this:

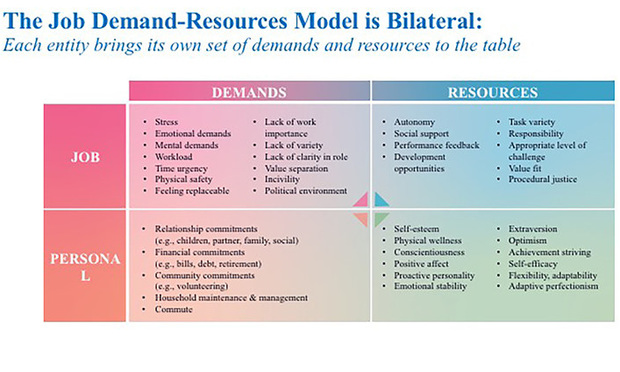

Your job can be divided into resources and demands. Resources are aspects of your job that give you energy and strength, like the satisfaction you get from being part of a really supportive team, or the happiness you get from writing a great brief, or helping a valued client think through a tricky legal problem. Demands are things that can help your energy, like the feeling of triumph you get when you win after a grueling trial, or sap your energy, like excess workloads or an environment where people are condescending. (A list of job demands and resources are set forth in the diagram below.)

If your job resources outweigh your job demands, you'll tend to be more engaged, and that energy will help you perform better. If the demands outweigh the resources, you'll lack the energy to do well, you'll tend towards burnout, and your performance is likely to suffer.

But the demands on our time and the resources we need to thrive at work are not entirely organizational. A lot of our energy comes from within: our attitude, our skills and our style of work, as well as whatever else is going on in our lives outside of work. Examples of these personal resources and demands are also set forth below.

At the end of the day, both the employee and the organization have a responsibility to try to maximize the resources and minimize the demands. The organization does this by communicating to its employees, listening to their concerns, and working to provide resources and reduce demands where it can. Employees do this by explaining what their challenges are, and by doing things outside of work that help them walk in to work with enthusiasm and energy.

Engagement won't occur without mutual communication and effort. As an attorney, you need to come to work prepared to do your job. But if there are things that either of us can control that will help you do that, we should talk about them.

If you feel you aren't getting enough clarity about your role, or there is training that you think will enhance your ability to succeed in that role, let's talk about that. If that training is expensive and takes you out of the office for extended periods of time, how can we best manage that? Are you having back problems that affect your ability to work? OK, we'll supply the standing desk and you commit to physical therapy. Are you unhappy with the actions of a colleague? Let's discuss appropriate ways to approach that conflict that will maximize the likelihood of a positive resolution and a shared sense of community, whatever the result. Are you having a major curveball in your personal life? Tell me what you're comfortable telling me, and let's see how we can help you during this limited period of challenge without damaging our responsibilities to our clients.

When we think about engagement as a two-way street, it changes the nature of the conversation. Managers should be aware that certain people and certain personality types are more prone to see things in a negative and cynical light. These people will need a little more patience and persistence in seeing the positive things that the organization is doing. On the other hand, these people can and should be working on improving their social networks within the firm by extending themselves to assist their colleagues.

Doing so will make the provision of support in times of high work or personal stress much more rapid, efficient and effective.

Read more – Minds Over Matters: An Examination of Mental Health in the Legal Profession

John F. Hollway is associate dean at University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School and executive director of the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice. He is also a member of Law.com's Minds Over Matters advisory board.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Letter From London: 5 Predictions for Big Law in 2025, Plus 5 More Risky Ones

6 minute readTrending Stories

- 1'It's Not Going to Be Pretty': PayPal, Capital One Face Novel Class Actions Over 'Poaching' Commissions Owed Influencers

- 211th Circuit Rejects Trump's Emergency Request as DOJ Prepares to Release Special Counsel's Final Report

- 3Supreme Court Takes Up Challenge to ACA Task Force

- 4'Tragedy of Unspeakable Proportions:' Could Edison, DWP, Face Lawsuits Over LA Wildfires?

- 5Meta Pulls Plug on DEI Programs

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250