The Paradox of Collaboration: In Law Firms, Individual Risk Is Key

Individual risk-taking, rather than collective goodwill, is the key to enhanced collaboration and law firm success.

December 12, 2019 at 12:28 PM

7 minute read

Catch a partner at a weak moment—say, in the bar after dinner—and ask them why collaboration at their firm is so hard. You'll hear something like what I heard recently: "My client is my livelihood. I can't risk having them like another partner more than they like me. I can't risk having another partner steal my client."

This is a sentiment that is as widespread as it is ill-founded. If clients didn't like you, they would already have found someone they do like. After all, clients are constantly being marketed to by partners from other firms. The real risk to one's practice is partners at other firms, not one's colleagues. Despite this logic, and for whatever set of reasons, partners perceive collaborating as entailing risk to themselves personally. Working this linkage in reverse begets the paradox of collaboration: the key to greater collaboration is for partners to take greater individual risk.

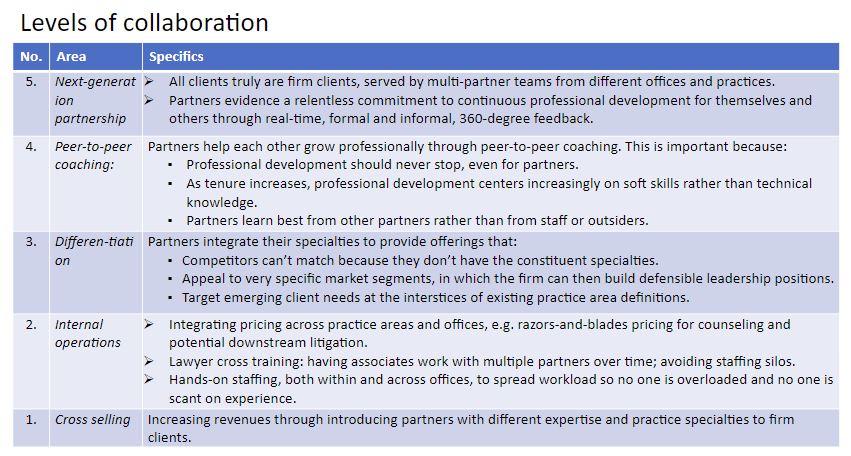

Levels of Collaboration

Before describing what this means for how to enhance collaboration, it's useful to step back and be specific about what we mean by collaboration. It's best thought of in levels, as shown below.

Most firms have progressed beyond thinking of collaboration as cross-selling (Level 1). They recognize the importance of collaboration to attorney development and pricing (Level 2) and, especially, to developing differentiated offerings (Level 3). Level 4 entails partners engaging in peer-to-peer coaching to constantly improve the performance of all partners and Level 5 encompasses all partners treating all clients as clients of the firm. Levels 4 and 5 represent collaboration as it is practiced at elite consulting firms; I know of no law firm functioning effectively at this level today. The first law firms to reach this level will distance themselves rapidly from their erstwhile peers.

Collaboration Isn't Pretty

In looking to enhance collaboration, it's important too to discard some naïve notions of what collaboration practice actually looks like in practice. Trading hearty greetings as partners pass one another's offices in the morning may reflect collegiality, but it doesn't evidence collaboration. Collaboration inherently entails conflict. Indeed, a zero-tension environment evidences partners engaging in parallel play, each in their own silo, rather than collaboration. When partners truly work together, risks are taken, people feel exposed, and tensions are inevitable.

There are a couple of classic cases of these tensions. One is the "coming of age" moment: A younger partner seeks to grow a client relationship and to do so has to take up more space with the client by, for example, having calls and meetings to discuss the client's needs without a senior partner, who has long been the face of the relationship, being present. Senior partners routinely struggle with the notion of their proteges being ready for such roles; less-tenured partners struggle with the notion that big-name senior partners don't move on to focus on opening new client relationships, arguably their highest, best use.

A second case is the "inertial incumbent" bottleneck: One partner has had a long-standing, steady stream of work from a client; another partner becomes involved with the client tangentially and, with new ideas and initiative, sets out to expand the relationship by having meetings, offering CLEs, and dining with client executives. The original partner feels usurped; the arriving partner feels shackled by the original partner's reticence.

The essence of collaboration is working through these kinds of tensions as grown-ups. It often requires the engagement of third parties, typically firm leaders, as facilitators of a dialogue between the discordant principals. This is a vital responsibility of leaders, one that few enjoy, and one that too many sidestep to the detriment of enhanced collaboration. Effective collaboration requires an acceptance and the development of a cultural norm, that no partner can passively exercise a veto by demurring on going along with what others determine is the best course of action for the firm.

Opportunities for Action

The action item here for leadership teams is to structure a dialogue among partners that allows them to deepen their understanding of collaboration. They should come to recognize that the key to better collaboration is not some action by leadership or some collective movement; rather, it's that they individually take more risk. It's helpful for partners to have a common language about things like the varying levels of collaboration, and an appreciation that, even though they may collaborate well today by historical standards, there are heights yet to be climbed. Similarly, it's useful for all to internalize that tensions are in inherent part of collaboration; rather than being avoided, they're to be worked through as adults.

For collaboration to improve at a firm, these observations have to be translated into goals that individual partners might set themselves. As an indication of what these might look like, below are some examples. They are grouped under three headings: client-focused, communications, and personal professional development.

Client-Focused

- I will look to work with partner X on expanding our firm's relationship at client Y, where I have a leading role.

- I will approach partner Y about how I could help her develop and expand the firm's relationship with client Z, where she has a leading role.

- I will reach out to partner P about working together to gain a foothold at organization Q, where our firm does not yet have a presence.

- On my next new matter, I will staff it using an associate team from outside my home office.

- I will find partners in practice area X to work with me on developing a cross-practice service offering that will help differentiate our firm's positioning and take it to clients A, B and C.

Communications

- I will orchestrate more communications (monthly conference calls, email distribution lists) for my fellow partners with interests in: a particular client or prospective client; a subspecialty within my practice area; or an emerging offering area that requires a combination of the specialties of partners from both my practice areas and others.

- I will ensure that calls I coordinate stay focused on action; accordingly, I will end calls by asking, "Who will do what by when?"

- I will invite a partner in my home office that I don't know well to lunch at least monthly.

- I will have coffee or lunch with a partner I don't know well every time I visit another office.

Personal Professional Development

- I will set goals for actions I will take to promote greater collaboration at my firm. I will memorialize these for myself by writing them down.

- I will ask a fellow partner I respect and trust to give me their reaction to these goals; I will invite them to check back in with me intermittently on how I am progressing on achieving them.

- After each significant milestone on a matter, I will ask for feedback from others, including associates; say thank you or offer commendation to others; and ask others if I can offer some thoughts related to things that went well and things that could have gone better on the matter.

A Closing Thought

Collaborating is not an innate ability of many lawyers; rather, it is a skill to be learned. Such learning is hard and can be exasperating. It's natural to feel occasionally that others aren't inviting you in to collaborate as they should. However, if you are experiencing this sentiment not just occasionally but frequently, you would do well to be open to the possibility that the problem lies not with others.

Hugh A. Simons is formerly a senior partner and executive committee member at The Boston Consulting Group and chief operating officer at Ropes & Gray. He writes and teaches about business aspects of law firms. Contact him at [email protected].

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Sullivan & Cromwell Signals 5-Day RTO Expectation as Law Firms Remain Split on Optimal Attendance

Eversheds Sutherland Adds Hunton Andrews Energy Lawyer With Cross-Border Experience

3 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Fulton DA Seeks to Overturn Her Disqualification From Trump Georgia Election Case

- 2The FTC’s Noncompete Rule Is Likely Dead

- 3COVID-19 Vaccine Suit Against United Airlines Hangs on Right-to-Sue Letter Date

- 4People in the News—Jan. 10, 2025—Lamb McErlane, Saxton & Stump

- 5How I Made Partner: 'Be Open With Partners About Your Strengths,' Says Ha Jin Lee of Sullivan & Cromwell

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250