How a Wilson Sonsini Partner Died From Drug Use and No One Saw It Coming

"It's hard to imagine addressing lawyer mental health and wellness without addressing the operational model of billable hours—to expect someone to not be depressed billing every six minutes," said Eilene Zimmerman, author of the new book "Smacked."

February 11, 2020 at 11:30 AM

9 minute read

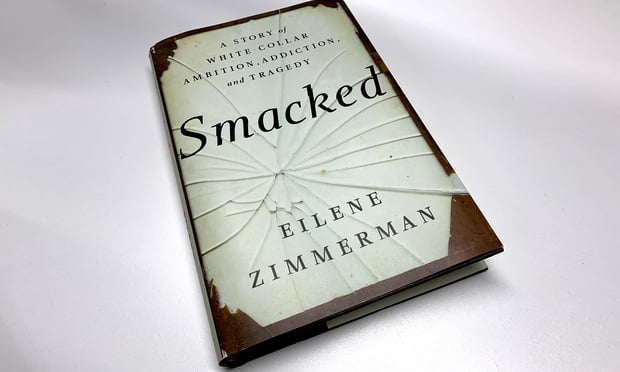

"Smacked," by Eilene Zimmerman.

"Smacked," by Eilene Zimmerman.

All of the signs were there. But none of the right conclusions were drawn. And it may not have mattered if they were.

All of the signs were there. But none of the right conclusions were drawn. And it may not have mattered if they were.

Weight loss, quick temper, constant illness, late-night trips to the convenience store that lasted for hours, frequent absences, missed deadlines, sleeping the weekend away, even tourniquets mailed to the office.

Those closest to the man, a partner in the intellectual property practice in the San Diego office of Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati, saw different pieces of the puzzle in the year or two leading up to his death in July 2015. But they all chalked it up to his being depressed or perhaps struggling with the thyroid condition he said he had. And he always blamed it on work. Client demands. The price of being a Big Law partner.

So when his ex-wife, Eilene Zimmerman, drove to his house one Saturday after their two kids said their dad was sick and acting strange the night before, she was expecting to find him sleeping and was ready to force him to get to the doctor.

Instead, Zimmerman found him unresponsive, lying on the bathroom floor. When she attempted CPR at the 911 dispatcher's advice, Zimmerman couldn't move his arm that covered his chest. He had died hours before.

In the chaos of those minutes after finding his body, Zimmerman didn't notice the drug paraphernalia around the room. It wasn't until the medical examiner said he likely died from a drug overdose that the idea of addiction occurred to Zimmerman. (It was ultimately determined he died from a heart infection obtained from IV drug use.) A toxicology report along with drugs tucked away throughout his house showed that he was using crystal meth, benzodiazepines, Adderall, cocaine and other drugs.

"By the time I realized what was happening, he had already died," Zimmerman said. She outlines that frantic day, and the confusing years before and after, in her new book "Smacked: A Story of White-Collar Ambition, Addiction and Tragedy." (In the book and in interviews, Zimmerman refers to her late ex-husband only as "Peter," to protect the privacy of her children, who share his last name.)

Zimmerman, a journalist who now has a social work degree, spent a lot of time over the past few years researching her ex-husband's trajectory and that of other lawyers who suffer from addiction, as well. The reporter in her had to know how this could happen to a prominent attorney. The wife in her—ex or not—had to know if she could have done anything to stop it.

"There were a ton of signs. I just didn't know they were signs, because I didn't think that was on the table for someone like Peter," Zimmerman said of his drug use. He was a well-educated, successful partner at a prestigious law firm.

After years of talking with lawyers, psychologists, academicians and others about white-collar addiction and life in Big Law, Zimmerman doesn't blame Wilson Sonsini or law firms in general, but she does think they need to change.

"I don't know what the answer is," said Zimmerman, adding that the culture inside law firms in general plays a role because "it's impermissible to talk about weakness."

Peter did a great job of hiding his addiction, or at least of convincing those around him it was anything but that. Despite absences and missed filings, he was dedicated to his work. When Zimmerman checked his phone, the last call he made before his death was dialing into a conference call.

The head of Wilson Sonsini's San Diego office, Jeff Guise, showed up at Peter's house within 20 minutes of the EMTs arriving and was there while Zimmerman and her two children spoke with grief counselors, the ME and police. After she confronted him, saying that the job killed her ex-husband, the office leader told Zimmerman that he had been missing work and that they encouraged him to see a doctor.

"I wish instead of not talking about it, I wish Wilson would have had an all-hands meeting and said, 'OK, we need to talk about our culture here' and say, 'OK, why was this guy afraid to ask for help," Zimmerman said.

Zimmerman and her ex-husband met in their 20s, and she said he was never an extremely happy guy, but he was "never as unhappy as when he was in law school and then after law school." She notes studies that say law schools teach students how to be negative, how to always look for problems. When their daughter was born while he was in law school, Zimmerman recalls Peter telling the doctor they'd be lucky if she wasn't pregnant and a drug addict by 15.

Along with the negativity and constant need to appease clients and those who would decide whether he'd become partner, Peter grew increasingly focused on financial status. He needed a bigger house, a better car, his kids had to go to private school.

"My friends would say, 'He's still working [so many hours] and he's a partner?" Zimmerman noted. "It felt like he just finished a marathon and got to the last mile and they said, 'Oh, there's 26 more miles to go.' There's always more money to be made. Why was a man making almost $1.5 million a year having to borrow against his draw?"

After he was partner, Peter ultimately had an affair with a law school classmate, and he and Zimmerman divorced.

"There are a lot of divorced attorneys," she said. "It's so hard because they are not present for the rest of their lives. And it pays such a lot, it's hard to walk away. He was always absent or working or sleeping."

Zimmerman begged him to go in-house, but he saw it as a step down. She said it is odd to her that none of his colleagues he worked with for 10 years pulled him into a conference room and asked him what was going on.

"Maybe in law you're never really friends because you are always competing for business," she wondered, acknowledging, however, that Peter likely would have lied. Leaders of several lawyer assistance programs told her that colleagues are so overwhelmed themselves that they often don't get involved.

Wilson Sonsini, the West Coast and Billable Hours

On the day of Peter's funeral, Wilson Sonsini provided a shuttle bus from the office to the funeral home, and several colleagues attended. Zimmerman hadn't yet told anyone how her ex-husband died. For all they knew, she said, it was the job that killed him. But when a young colleague was holding back tears during a eulogy, Zimmerman looked back to see several of the lawyers on their phones, working, Zimmerman assumed.

In writing her book, the firm would only allow the general counsel to speak with Zimmerman. But she says the firm has been supportive in many ways. It was the first to buy the book—70 copies, in fact—and is sponsoring a Feb. 12 book signing in San Diego where Zimmerman will speak about issues of addiction in the law.

"Substance abuse and wellness are issues that Wilson Sonsini takes very seriously," firm spokeswoman Alicia Towler White said in an emailed statement. "We applaud the strength, bravery, and fortitude that Eilene has demonstrated by telling her and Peter's important story, and we hope her efforts will be the impetus for law firms and other organizations to take meaningful and effective action."

The firm has since encouraged employees to use its employee assistance program called Health Advocate, and it has signed the American Bar Association pledge regarding mental health and substance abuse, along with supporting other programs.

Zimmerman says firms are genuinely trying, and the biggest hurdle will be overcoming lawyers' distrust of the programs.

"If I was a partner with that much at stake, would I call the EAP line?" she said.

Zimmerman said Peter chose a West Coast firm over a New York offer because he thought it would be more relaxed. And in some ways it was. He didn't have to wear a tie.

"In the end, it was just as intense in terms of billable hours as any white shoe firm in the Northeast," Zimmerman said. "When he became a partner, I remember thinking, 'OK, that's over,' and then he said, 'No, it's just the beginning of another ladder. Now I have to get clients.'"

Firms need to be more authentic in their dialogue and start to buy into the concept that healthy lawyers equate to healthy profits. But the biggest question is whether this issue can be fixed under the existing business model of most firms.

"It's hard to imagine addressing lawyer mental health and wellness without addressing the operational model of billable hours—to expect someone to not be depressed billing every six minutes," she said. "When he died, it was written on so many lists—time, time, do time."

"The more we talk about it, eventually I hope it will be OK to admit that you are not OK," Zimmerman said.

Read more – Minds Over Matters: An Examination of Mental Health in the Legal Profession

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

KPMG's Bid to Practice Law in U.S. on Indefinite Hold, as Arizona Justices Exercise Caution

Orrick Hires Longtime Weil Partner as New Head of Antitrust Litigation

Sidley Adds Ex-DOJ Criminal Division Deputy Leader, Paul Hastings Adds REIT Partner, in Latest DC Hiring

3 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1US Supreme Court Considers Further Narrowing of Federal Fraud Statutes

- 2Rudy Giuliani's Story Arc in the Southern District of New York

- 3Don’t Blow It: 10 Lessons From 10 Years of Nonprofit Whistleblower Policies

- 4AIAs: A Look At the Future of AI-Related Contracts

- 5Litigators of the Week: A $630M Antitrust Settlement for Automotive Software Vendors—$140M More Than Alleged Overcharges

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250