Eric Holder, Evercore Litigation Chief Urge 'Hope Over Cynicism' on Diversity in Law

The former attorney general and Brogiin Keeton discussed progress, obstacles and paths forward for the industry.

February 25, 2020 at 05:13 PM

9 minute read

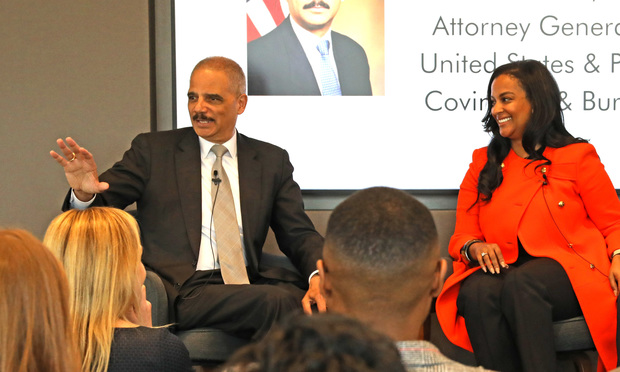

Eric Holder of Covington & Burling and Brogiin Keeton, head of litigation at Evercore (Photo: Evercore)

Eric Holder of Covington & Burling and Brogiin Keeton, head of litigation at Evercore (Photo: Evercore)

A morning meeting between lawyers at a Manhattan investment bank may not be everyone's idea of a "fireside chat." But that's how global independent bank Evercore billed a discussion it hosted last week between its in-house litigation head, Brogiin Keeton, and Covington & Burling partner Eric Holder.

The topic of the meeting, timed to celebrate Black History Month, was diversity. And while the internal meeting was closed to outsiders, Keeton and the former U.S. attorney general caught up with ALM afterward to talk about diversity and inclusion in the legal industry—and about their experience moving up the ranks as black attorneys.

Holder, the country's first black attorney general under its first black president, has been outspoken on diversity issues, and he had made them part of his practice at Covington. In 2018, he led Uber's internal investigation into the tech company's workplace harassment and discrimination, and last year the American Institute of Architects tapped him to review its rewards and honors process, according to Architectural Digest.

Keeton, a former Sidley Austin associate, joined Evercore as head of litigation in 2015. She is also a leader of the firm's diversity and inclusion initiatives.

The conversation has been edited for clarity and style.

As two prominent black attorneys, do you think real progress has been made in regards to diversity and inclusion in the legal industry?

Holder: Look at [Covington's] last partnership class. We had 14 new partners in our last class, nine of whom were women and six people were of a diverse background. Twenty-four percent of our equity partners are women, and three-eights of our management committee is female. These are all positive markers, and I think it shows that Covington is in a fundamentally different place than it was 20 years or so ago. I think you can find other markers within the profession that show it is changing. And yet, we're not where we need to be if you look at the number of judges, partners at law firms and general counsel who are women or people of color. There are still barriers women and people of color have to deal with, but the fact that Evercore had this conversation today is a marker of progress, even though we've not yet gotten to the place were we can honestly say we've achieved all that we should.

Keeton: The idea that I, as a woman of color, get to sit in the seat that I'm in—head of litigation at a public, premiere investment bank—that says something. It says something about the company I work for, but also about the work people like Eric and others have put in to allowing talented people to thrive, regardless of their background.

What are the main barriers people of color and diverse attorneys are still facing in the legal industry?

Keeton: There have been a lot of times when I have walked into a room and people's assumption was that I must be the assistant or that I must be the most junior member of the team. I don't think that comes from a place of malice—I think it comes from a place of expectations. When you see "head of litigation," you probably expect someone who is male, of a certain age, and probably somebody who isn't black. But the more people like me who exist, just existing can change people's mindsets and expectations.

Holder: This notion of "barriers"—things like [Keeton's] grandparents faced and like my parent's faced—those are not really things that, by and large, we're dealing with now. But there are still different kinds of impediments, if not barriers. They are impediments of expectations: the surprise that the head of litigation is a competent, African-American woman. That's a different society than the one that existed years ago where you didn't want a person of color or woman of color in that position and assumed all kinds of negative things about them. I think that's a marker of success, but still an indication we're not yet where we need to be.

We have to get to a point where when [Keeton] walks into a room, there's not an assumption made about who she is or a degree of surprise expressed at finding out what her position is.

Many clients have moved beyond general demands for "diverse" legal teams to require specifics from outside counsel—for example, the first chair should be a woman or a certain percentage of the group should be racially diverse. What are your thoughts on these specific benchmarks clients are asking of law firms?

Keeton: I understand the impetus behind this intense focus on exactly how matters should be staffed, but I don't pursue that. For me, the promotion of diversity and inclusion is really a long conversation and a long partnership [between me and my law firms]. If you're in partnership with your law firm, then you don't make demands and micromanage in a way that often misses the point, which is that I want to make sure people from all backgrounds really have opportunities on my cases, and that the diversity of my firms reflect my and Evercore's own values. Because of pipeline issues, that might not happen in a way that is ideal on every single case, and if I'm penalizing my law firms each time they don't [meet a diversity benchmark], I think that has a little bit of shortsightedness.

It's not enough to just include a woman of color on your team to be diverse. Are you training that person? Is this person right for this matter? That's why I think it's dangerous to micromanage as opposed to having a conversation. The result of my conversations is that I end up with very diversely staffed matters, but I'm also able to building relationships with most of the attorneys.

Holder: From the law firm perspective, if we're going out to pitch for an assignment, we keep in our minds at Covington that we want to present a diverse group of people who have the capacity to do the task we're seeking to be involved with. But as I'm putting together a diverse team, I'm not sacrificing excellence when I put that team together. There's not a tension between diversity and professional excellence.

Do you find that most law firms are genuine when it comes to their diversity and inclusion efforts, or can you tell when it's just lip service?

Keeton: Time tells a lot. If you show up to the first meeting and I see a diverse bench, but I give you [more work] and I stop seeing that, I kind of know what the deal is. I do think because people have been so vocal, that law firms have listened. If we have an investigation, you can't have people approaching a problem all from the same perspective. If it's all one homogeneous group, you might miss out on talking to the right person in a way that resonates with them, because nine times out of 10, the person raising their hand saying they have a problem is not a part of the majority.

Holder: There was a recent statement by the client base where a lot of general counsel said they wanted more diverse teams. I think that's been inculcated at Covington and at other firms as well. It's almost now as you're forming up a team, on a subconscious, unconscious bias, you put together teams that look diverse. This is not only in response to what clients say they want to see, but also because when you're looking for what's going to be the best team, you want people with different backgrounds, experiences and worldviews. That's going to be the team that's going to come up with the best solutions for the client.

Where do we go from here?

Keeton: The idea of hope over cynicism is critical. I think when you sometimes stop and you think of all the things you want to change and want to do, it can be easy to be overwhelmed and not always be optimistic. But for me, I get to wake up everyday, go to a place and do a job have a lot of fun at. And in doing that, I hope that I give other people permission to live their best lives and work on policies that push forward that sense of identity and inclusion. That doesn't happen if you're not hopeful or optimistic.

Holder: At the end of the day, I'm optimistic about this. I've lived long enough to see changes, the likes of which I could not have anticipated as a young man. I served in the administration of a black president. If you told 15-year-old Eric that in his lifetime there would be a black president, I would have thought that was impossible. A young, skinny black kid from Queens is going to be attorney general of the United States? Yeah right. And yet, it happened. We're not yet where we need to be, but I'm actually optimistic we can actually get to that place.

Read More:

170 GCs Pen Open Letter to Law Firms: Improve on Diversity or Lose Our Business

One Year Later: Has the General Counsel Open Letter on Diversity Had an Impact?

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Covington, Steptoe Form New Groups Amid Demand in Regulatory, Enforcement Space

4 minute read

Consumer Finance Law Enforcer Takes Private Practice Job at Morgan Lewis

With 'Fractional' C-Suite Advisers, Midsize Firms Balance Expertise With Expense

4 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1'It's Not Going to Be Pretty': PayPal, Capital One Face Novel Class Actions Over 'Poaching' Commissions Owed Influencers

- 211th Circuit Rejects Trump's Emergency Request as DOJ Prepares to Release Special Counsel's Final Report

- 3Supreme Court Takes Up Challenge to ACA Task Force

- 4'Tragedy of Unspeakable Proportions:' Could Edison, DWP, Face Lawsuits Over LA Wildfires?

- 5Meta Pulls Plug on DEI Programs

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250