What To Do About the First-Year Class of 2020?

Hugh A. Simons argues that the incoming first-year associate class for the fall of 2020 should be deferred. He offers historical perspectives from the Great Recession and guidance on when and how to implement these decisions.

April 16, 2020 at 03:01 PM

10 minute read

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

Yet more decisions between bad and worse are upon us. The class of 2020 is due to start arriving in less than six months. There's not going to be enough work for them; they should be deferred. But what should the new start date be? Should firms pay some kind of stipend? When and how should the changes be announced?

New start date

One factor influencing start dates is bar exam timing. New York called off its July exam and Massachusetts, Connecticut and Hawaii have already followed. In response, The National Conference of Bar Examiners has said it will offer exams on September 9 and 10 and also on September 30 and Oct. 1. With backup dates now established, more states are expected to cancel their July sittings.

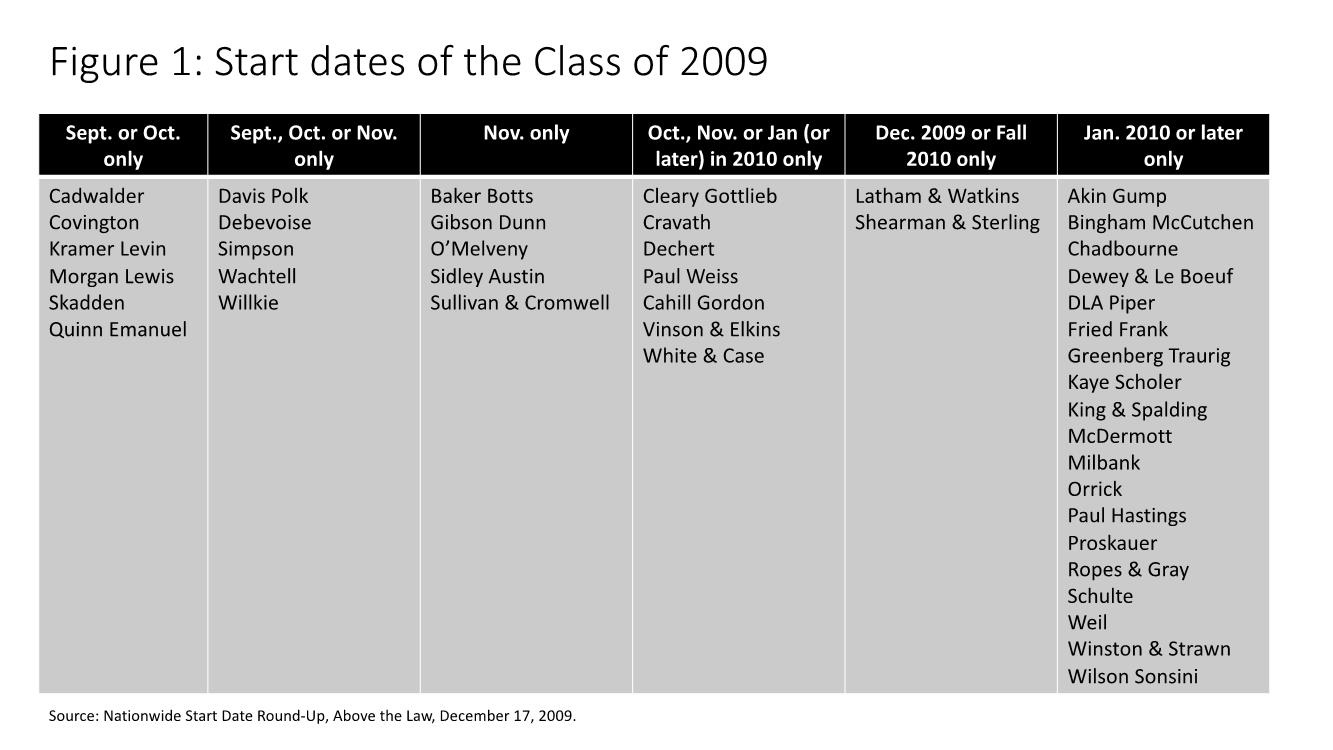

To allow the new associates time to recover from the exams, and yet not have them arrive as the holidays hit, deferring them to January 2021 is an option. There's precedent for January starts from the class of 2009. Figure 1 summarizes the start dates offered by the 42 of the 50 most profitable firms on the 2009 Am Law 100 for which information was reported in the law blog world.

As the figure shows, it was a mix with many firms offering multiple starts. Only six firms stuck with just September or October starts; a further five offered November as an option, and yet five more offered only November. In all, twenty-eight of the forty-four firms offered 2010 start dates, of which nineteen offered only starts in 2010.

If not a success, the deferrals were at least considered to have been the lesser of two evils. Indeed, many firms used deferrals again with the class of 2010. Students didn't love it but delays were so widespread firms weren't especially punished. Opprobrium was reserved for those who rescinded offers.

However, given the outlook for economic activity, having the class of 2020 arrive in early 2021 would probably be to have them join too soon. Economic forecasting is to be approached with great humility at a time like this, but, if things transpired as Goldman Sachs projected in their latest revision, then in Q1 of 2021 the level of U.S. economic activity would be the same as that of early 2018, i.e. the level of two years ago; it is not until late 2021 that the economy is projected to regain its late 2019 levels.

Infographic credit: Tim Schafer

The Goldman Sachs forecast is one of the less optimistic ones out there. But even if the economy recovers more quickly, there is a case for a deferral to late 2021:

- While it has yet to show up in the HR reports, voluntary attrition has stopped. Current associates won't be going anywhere under their own steam until fall of 2021 at the earliest. Layoffs are more reputationally damaging than deferrals.

- Industrywide, the class of 2020 portends to be a huge class, surpassing even the historic peak of 2008-09. According to the National Association for Law Placement (NALP), the average 2019 summer class was the same size as that of 2008 but the 2019 offer and acceptance rates were significantly higher than those of 2008 (97.6% vs. 89.9% for receiving offers, and 87.5% vs. 79.7% for accepting offers). The class would be a challenge to get busy under normal business conditions.

- Having junior associates be busy is essential to their amassing the requisite experience to become the truly-effective mid-level associates that clients love. Having too many associates on board spreads the work too thin for appropriate growth, seeding a quality problem for the medium term.

- If fresh associates are needed sooner then we know from last time, then associates can be brought on (selectively by practice or office) prior to the date to which they were originally deferred. Obviously, this has to be done within some constraints, e.g. you wouldn't want to pull an associate from a clerkship and risk vexing a judge.

All this is to say that firms should seriously consider pushing the arrival of the class of 2020 past January 2021 and out to fall 2021 or even January 2022. It can be done selectively, e.g. excluding restructuring, labor and employment, life sciences regulatory or litigation groups that have landed a whale.

Financial support

The precedent on offering financial support to incoming associates is broadly misunderstood. There were industry-wide deferrals of the classes of both 2009 and 2010. The former garnered the lion's share of attention, and stick in the memory, because they took people by surprise; the latter may be more instructive in the present situation.

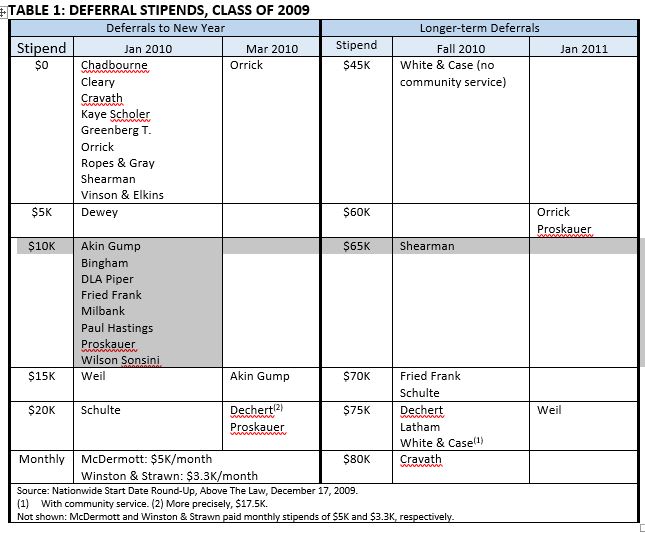

For the class of 2009, the law blog world tracked the deferral dates and stipends with vigor. As Table 1 shows, for deferrals to early 2010, firms were roughly evenly split between offering no stipend and a stipend of about $10,000. McDermott, Will & Emery and Winston & Strawn took an approach that may be apt for the present uncertainty—they paid a stipend on a monthly basis. For the longer-term deferrals, those to fall 2010 and early 2011, stipends were a standard part of the arrangement and ranged from $45,000 to $80,000. The longer-term deferrals had linkages to taking positions at not-for-profits that were generally pretty loose. What was really happening is that firms were leveraging their pro bono client relationships to gin up opportunities that they hoped would induce incoming associates to voluntarily delay their arrival by a year. Pro bono coordinators had never been so busy.

However, for the class of 2010, things changed. The law blog world took deferrals in stride, reducing the quantity of coverage and toning down the snark. While some firms went again with stipends for those deferred to January (e.g. Sidley Austin, Milbank), Skadden, Arps, Slate Meagher & Flom changed things up. It offered a salary advance rather than a stipend—$15,000, comprising $5,000 in April 2010 and $10,000 upon receipt of final law school transcript, to be repaid out of first year salary. They weren't lambasted on the blogs. Indeed, Above the Law quipped in March 2010: "Sorry, 3Ls, money for doing nothing is so 2009" and "Last year was a different ballgame with deferrals taking incoming associates by surprise. This year, offering salary advances instead of stipends might not be unreasonable."

The financial arrangements for year-long deferrals were similarly modulated. For example, Cravath, Swaine & Moore had offered an $80,000 stipend to associates to voluntarily delay their arrival from fall 2009 to fall 2010, but when they mandatorily deferred the full-time arrival of the summer class of 2009 from the fall of 2010 to that of 2011, they provided a deferral stipend of just $65,000.

The implication is that salary advances (rather than stipends) will probably be 'market' for deferrals to January 2021 and that $65,000 stipends will probably be 'market' for one-year deferrals.

Timing of announcement

Law firms are reticent to announce delayed start dates. It's perceived as connoting financial weakness. There is some basis for this in history, but it's misleading unless unpacked a little.

Back in 2008, Thelen, Thacher, Heller Ehrman and Powell Goldstein pushed the start dates for their classes of 2008 to January 2009. By January of 2009, the first three of these firms had dissolved and Powell Goldstein had combined with Bryan Cave. With some justification, this may be what begat the notion that deferring start dates is a sign of weakness.

However, 2009 was a different story. It started with some prestigious names announcing 'delayed starts' from traditional September dates to later in the fall, evolved to include 'deferrals' to December 2009 and January 2010, and ultimately incorporated optional deferrals to the fall of 2010 and January 2011. Here is how it went:

- January (2009): September starts delayed to later in fall at Clifford Chance, Milbank and Morrison & Foerster.

- February: longer delays announced by Hogan & Hartson (to November 30), Latham & Watkins (to mid-December or fall 2010), and Nixon & Peabody (to January 2010).

- Early March: deferrals to January 2010 announced by O'Melveny & Myers, Chadbourne & Parke, Venable and White & Case (for most).

- March 10th: Cravath announced it too was deferring arrivals and offering start dates of October, November or January.

- Late March and early April: By April 6th over 30 firms had announced push backs.

I don't believe that firms who announce incoming class deferrals now risk being perceived as dangerously weakened. Partly this has to do with the different profiles of the 2008 and current recessions. In 2008, the economy went into a slow quarter-by-quarter decline causing firms with less financial wherewithal to publicly evidence stress sooner than those of greater financial strength. In contrast, the comparative nose dive of the current recession negates serial exposure of firms of differing financial strength.

Infographic credit: Tim Schafer

Given this difference, nothing can be read into how quickly firms react. Further, firms who now announce deferrals of arriving associates can't be considered the especially-financially-pressured movers. Those who could be viewed as akin to the first movers in 2008 (Thelen, etc.) are among those who made significant moves in the last 2-3 weeks. There's a long list of such firms that includes Baker Donelson, Brown Rudnick, Cadwalader, Curtis, Loeb & Loeb; Norton Rose Fulbright, Reed Smith, and Womble Bond Dickinson.

The implication? There's no abnormal reputational risk in announcing deferrals now. It would be well received by current associates who'll recognize it avoids increasing the competition for what work is available.

Closing thought

It's tempting for firms to delay announcing decisions about the arrival of the class of 2020 as we await greater clarity. However, we are already past the time in 2009 by which most firms had announced. There's also an important benefit to incoming associates from moving soon: delay weakens their prospects of securing prestigious paid public interest work and entry into elite LL.M. programs.

Hugh A. Simons is formerly a senior partner and executive committee member at The Boston Consulting Group and chief operating officer and policy committee member at Ropes & Gray. Early retired, he now researches and writes about the business side of law firms and does some consulting for old friends. He welcomes reader reactions at [email protected].

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Paul Hastings, Recruiting From Davis Polk, Adds Capital Markets Attorney

3 minute read

Kirkland Is Entering a New Market. Will Its Rates Get a Warm Welcome?

5 minute read

Goodwin Procter Relocates to Renewable-Powered Office in San Francisco’s Financial District

Law Firms Mentioned

- McDermott Will & Emery

- Ropes Gray

- Hogan Lovells

- Cravath, Swaine & Moore

- Nixon Peabody

- Loeb & Loeb

- White & Case

- Latham & Watkins

- Brown Rudnick LLP

- Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner

- O'Melveny & Myers

- Clifford Chance

- Morrison & Foerster LLP

- Sidley Austin

- Venable

- Baker, Donelson, Bearman, Caldwell & Berkowitz, PC

- Reed Smith

- Norton Rose Fulbright

- Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP

- Womble Bond Dickinson

- Winston & Strawn LLP

Trending Stories

- 1A Judge Is Raising Questions About Docket Rotation

- 2Eleven Attorneys General Say No to 'Unconstitutional' Hijacking of State, Local Law Enforcement

- 3Optimizing Legal Services: The Shift Toward Digital Document Centers

- 4Charlie Javice Fraud Trial Delayed as Judge Denies Motion to Sever

- 5Holland & Knight Hires Former Davis Wright Tremaine Managing Partner in Seattle

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250