Why More Firms Should Cut Salaries Sooner Rather Than Later

As we approach the end of April, firms are running out of time to materially reduce 2020 costs, Hugh A. Simons writes. Salary cuts have appeal not just because compensation comprises about two-thirds of total cost, but also because they deliver immediate savings.

April 27, 2020 at 03:36 PM

6 minute read

(Photo: Andrey_Popov/Shutterstock.com)

(Photo: Andrey_Popov/Shutterstock.com)

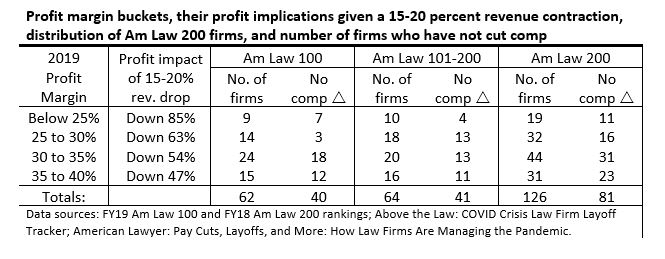

The consensus estimate for 2020 revenue is a decline of 15 to 20 percent from last year. And yet, as of April 26, less than a quarter of the Am Law 200 have reduced salaries or laid off personnel. This feels like a sluggish response given what the partner profit implications might be. A simple analysis supports this intuition.

There are 126 Am Law 200 firms who face declines in profit of a half or more under such a revenue contraction (with costs contained at last year's level). There has been no reported action to reduce comp, law firms' dominant cost item, at 81 of these firms. Even allowing for noise in the numbers, there are a lot of commercially-strong partners who are being expected to endure eye-catching drops in compensation. Some will be lured away to firms that are performing more strongly either because of practice mix or faster movement on cost reduction. Partner departure numbers, low at first, will snowball at some firms. A quick back-of-the-envelope calculation indicates we can expect to see 10 to 15 firms fold.

Analysis

The analysis looks at the effect of revenue decline on profitability through the lens of profit margin, that is: profits as a percent of revenue. It works as follows: if last year a firm had a profit margin of 50 percent and this year revenue falls by 10 percent then, with costs held at last year's level, profits would fall to 40 percent of prior year revenue—a 20 percent drop (from 50 to 40 percent of last year's revenue).

The table below applies this framework to the Am Law 200. Each row corresponds to a particular range, or 'bucket', of 2019 profit margin. The second column shows the change in profitability from 2019 to 2020 for firms in each bucket if revenues fall by the consensus estimate of 15 to 20 percent (and costs held flat). For firms in the 35 to 40 percent bucket, profits would fall by 47 percent from their 2019 level, i.e. they'd essentially be halved; firms in the lower buckets would see greater, and some stunning, declines.

The surprise here is not the scale of profit contraction; law is, after all, a largely fixed cost business. Rather, the surprise is the number of firms who have not moved to cut compensation. As the rightmost two columns of the table show, there are 126 Am Law 200 firms with 2019 profit margins in the 35-to-40 percent bucket and below; of these, 81 firms have not had salary reductions or layoffs. This dynamic applies equally to Am Law 100 and 'second hundred' firms. As the middle columns of the table show: 62 and 64 Am Law 100 and second hundred firms, respectively, face profit declines of a half and more, of which 40 and 41, respectively, have not reduced comp.

An aside on cost: law firms often describe their cost cutting as reductions from budgeted levels. The reason for this is that there's a momentum to cost growth—associates move up a year in salary, staff get annual 'merit' increases, rents have escalation clauses, medical insurance costs rise, last-year's hires now incur full-year costs. To improve the profit outlook scenarios above, costs have to go below 2019 levels. This is particularly a challenge because momentum growth is exacerbated by voluntary attrition having basically stopped. As we approach the end of April, firms are running out of time to materially reduce 2020 costs. Salary cuts have appeal not just because comp comprises about two-thirds of total cost (and of the remaining third, more than half is rent and depreciation) but also because they deliver immediate savings (unlike layoffs which entail severance payments).

Implications

How can it be that so many at-risk firms have not moved to cut compensation? First, a couple of caveats on the analysis: some firms' compensation cuts may have gone unreported; for others, their particular business mix may objectively support a stronger revenue outlook. It could also be that firm leaders are articulating greater revenue declines than they truly anticipate. Even allowing for these moderations, it has to be that the lack of movement on compensation at many firms is because partners have said they're prepared to take the hit.

It's unclear that partners will stick to these avowals. As the shock of the pandemic's onset recedes in memory, the prevailing soft demand environment will come to be accepted as a sort of normal. Partners at struggling firms will watch peers at rivals doing significantly better (due to business mix or earlier compensation cuts). Competitors will start calling commercially-strong partners, enticing them to move. Partners won't leave because their firm is having a bad year in the midst of the pandemic; it'll be reframed in their minds: they're leaving because of loss of confidence in leadership, concern about capital accounts, or desire to be part of a winning team. They'll see partners at other firms, and then at their own, move laterally; they won't want to be left behind. It's not the profit drop that imperils firms, it's the partner departures its prospect precipitates.

I don't see how all 81 of the low-margin, no-comp-cut, firms can survive. Let's say either the data are wrong, or the revenue outlook is stronger, for a half of these firms. That would mean 40 firms come under partner departure pressure. If departures take hold at, say, just a third of these firms then, in round numbers, ten to fifteen firms will go under.

Absent significant movement, and soon, this will not end well.

Hugh A. Simons is formerly a senior partner and executive committee member at The Boston Consulting Group and chief operating officer and policy committee member at Ropes & Gray. Early retired, he now researches and writes about the business side of law firms and does some consulting for old friends. He welcomes reader reactions at [email protected].

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Three Akin Sports Lawyers Jump to Employment Firm Littler Mendelson

Brownstein Adds Former Interior Secretary, Offering 'Strategic Counsel' During New Trump Term

2 minute read

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1How ‘Bilateral Tapping’ Can Help with Stress and Anxiety

- 2How Law Firms Can Make Business Services a Performance Champion

- 3'Digital Mindset': Hogan Lovells' New Global Managing Partner for Digitalization

- 4Silk Road Founder Ross Ulbricht Has New York Sentence Pardoned by Trump

- 5Settlement Allows Spouses of U.S. Citizens to Reopen Removal Proceedings

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250