Are Layoffs Coming? And If So, Who Will Be Impacted?

Hugh A. Simons explores whether the legal industry will experience layoffs in the months ahead, using data to predict which attorney segments may be impacted and at what rates. Simons also explores how firms should handle cuts differently than they did in the Great Recession.

June 01, 2020 at 03:39 PM

11 minute read

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

Big Law experiences peaks and troughs in demand following the business cycle. But it also undergoes a more pronounced, and less discussed, cyclicality: chunky ups and downs in the number of lawyers it employs. It's an innate part of the business, and one with implications for what happens next in the COVID-19 recession. We'd do well to prepare ourselves.

Lessons from the recession of 2008-10

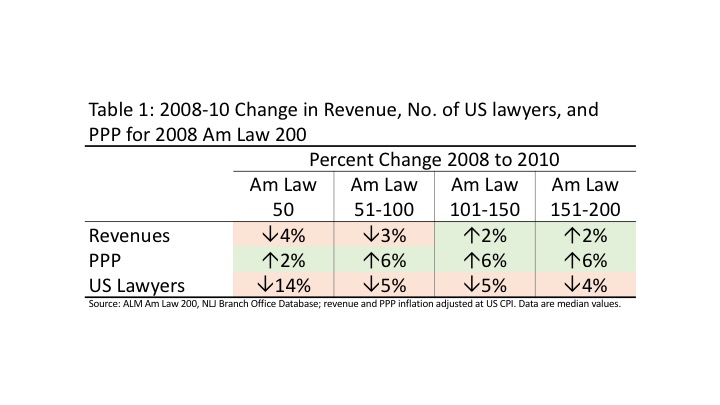

Let's start with some data. Table 1 shows the 2008-10 growth in revenues, number of U.S. lawyers and PPP (profit per equity partner) for the Am Law 50, second fifty, etc. These are median values (meaning half the firms in each cohort saw higher, and half lower, changes) and so are not distorted by mergers or dissolutions. A number of things stand out:

- The revenue drop was greatest for the Am Law 50. This is not surprising as their business models are both more hits driven (i.e. dependent on very large transactions or litigations) and more international.

- Am Law second hundred firms did not endure revenue declines, but rather had modest increases (even after inflation). Some of this is because of the nature of the work they do—routine work that had to get done more by outside firms as client companies laid off their in-house lawyers—and some because clients went to smaller firms in search of lower rates.

- All cohorts increased PPP, although the Am Law 50 increased less than the others.

- The number of U.S. lawyers declined across all cohorts, with the Am Law 50 declining markedly more than the others.

Two new associate classes arrived during the period. Thus, the reduction in number of lawyers shown underrepresents the number of lawyers that actually departed. We can use entry-level intake data from the National Association of Law Placement (NALP) to account for this. As shown in Table 2, total lawyer departures from 2008 to 2010 were 23% for very large firms (501+ lawyers, roughly Am Law 1-90) and 16% for large firms (251-500 lawyers, roughly Am Law 90-160). Given that voluntary attrition is essentially zero in a recession, these numbers indicate the scale of involuntary departures.

Why do departures on this scale happen? In a strong economy, firms experience high voluntary attrition—often of over 10% annually. At the same time, firms need to meet the demands of clients or risk losing their trust—nothing is worse for long-term relationship building than to tell a client "we don't have the capacity to serve you right now." So, summer and fall class sizes are increased; review standards are eased for those on the partner track; lateral recruiting from firms lower in prestige and profitability is ramped up; and, when it comes to time for crunchy decisions like making up equity partners, holding zones are created—people are moved into counsel and nonequity partner roles (and, because demand is strong, having people in these roles doesn't take work from on-track lawyers and hence doesn't deprive them of experience needed to develop).

But then the economy turns, demand eases, and the risk of having to turn down work evaporates. Another concern takes its place: if work is spread among too many lawyers, none acquire the experience necessary to keep progressing at the appropriate rate; having broadly-underexperienced cohorts of lawyers would cause client dissatisfaction and undermine relationships built through multiple years of relentlessly high-quality service. A streamlining of the partner-track ranks takes place so that the highest-potential associates are kept busy enough to grow at the appropriate pace; the holding zones created in the boom are vacated so they can be refilled during the next up-cycle.

The streamlining phenomenon is not unique to law; it happens in all high fixed-cost businesses (steel, chemicals, paper): the marginal capacity that's needed to meet peak demand is taken off line when the cycle turns. What is unique to law is that it's not explicitly acknowledged. It's distasteful to say out loud although, in fairness to the industry, it's implicit in paying twenty-somethings with no real experience a base salary of $190,000.

Overlaying the above cyclical dynamic is a profound secular trend: continuously raising the commercial prowess of the equity partner cohort. Equity partners at elite law firms have to be more than excellent lawyers; they've to be consummate relationship builders and adroit project managers. There are places for equity partners with $2-3M books of business billing 1,500 hours annually but they are no longer at elite firms. The work on raising the prowess of equity partners proceeds in earnest when the cycle turns—home-grown partners who have proven unable to evolve to the new standard, and laterals who have been so-so but not truly met expectations, are transitioned out. It's certainly harsh but, unlike young lawyers exited in the downturn, partners can't credibly say they got no warning—the changing nature of the industry is no secret.

Overlaying the above again is a secular trend toward widening of comp ranges within the equity partnership. Because a downturn squeezes the profit pool, it increases the attention given to how individual partners' distributions from the pool align with their contributions to the pool. At most firms there is less variation in distributions than in contributions, so the drift toward greater alignment of the two results in a widening of comp ranges.

Implications for the recession of 2020-22

There's an innocence to some of the commentary accompanying the ongoing round of salary reductions. They will transpire to be stop gap measures adopted by firms cognizant of the implausibility of firing someone over Zoom in the middle of a pandemic. While salary cuts shore up firms financially, the don't address the fundamental problem: more lawyers than can be kept busy enough to grow professionally at the required pace. Thus, we should expect layoffs as people return to their offices. We should also anticipate churning of the equity partner ranks and another round of widening of equity partner comp ranges.

Will the departures be on the same order-of-magnitude as 2008-10? There are a number of factors to consider. The recession of 2008 is characterized as having been unusually prolonged; in contrast, economists are talking of the COVID recession as short and V-shaped. This is encouraging. But we need to listen carefully to what's being said. Economists focus on the rate of growth of the economy; when it goes from negative to positive, they think of the recession as over. What matters to law firms is not the rate of growth but the absolute level of economic activity; for a law firm, the recession ends when the level of economic activity (not its growth rate) returns to pre-recession levels. The forecasts project growth in economic activity to turn positive in Q3 2020 and the level of economic activity to regain pre-recession levels in early 2022, nine quarters after the pre-recession peak. This is not significantly shorter than the ten quarters it took for economic activity to regain its Q2 2008 pre-recession high in 2008-09 recession.

There is a difference too in the sector incidence of the two recessions. The 2008 recession wiped out the mortgage backed securities business and the firms heavily dependent on it (Thacher Proffitt and WolfBlock dissolved; McKee Nelson merged staggeringly into Bingham McCutchen). The recession was hard too on banks generally and, banks being a stalwart client base, thus on law firms broadly. An emerging view is that the COVID-19 recession will be different: the industry segment being wiped out is travel and tourism, not a sector upon which law firms are especially reliant. On closer examination, however, this may not offer great comfort. Banks are not as immune as some perceive: while the Dow Jones US Travel & Leisure Index was down 28 percent for the first four months of 2020, the Dow Jones US Banks Index was down even more, 35 percent.

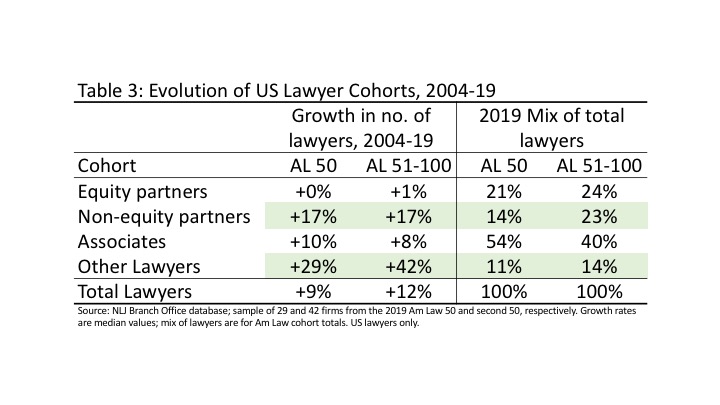

We saw a large increase in entry-level hiring going into the 2008 recession. The National Association for Lawyer Placement (NALP) tells us the arriving JD classes at very large firms (501+ lawyers) grew from 4,000 in 2006 to 4,700 and 5,200 in 2007 and 2008, respectively. This time, the increases have been more muted and to lower levels: from 4,200 in 2016 to 4,600 and 4,800 in 2017 and 2018, respectively. This portends less pressure on younger lawyer cohorts. However, we have seen significant build up in lawyer numbers in other cohorts. While the number of equity partners has been essentially flat at the median Am Law 100 firm, the number of nonequity partners as grown strongly, and those in 'other' categories (counsel, career attorneys) have grown more strongly still, see Table 3. These two cohorts have consistently recorded below-average hours at most firms and they are not small groups—as Table 3 also shows, these cohorts comprise 25 and 37 percent of total lawyers at Am Law 50 and second 50 firms, respectively.

We can expect to see lawyer reductions to be biased to these cohorts. That said, we should not expect pyramids to return to their decade-ago shape. An important response for law firms to adopt as market power shifts to clients is to make greater use of lawyers who are long-term in specialized roles and to avail of greater numbers of nonequity partners to help free up partner time for relationship development and high-level client counseling.

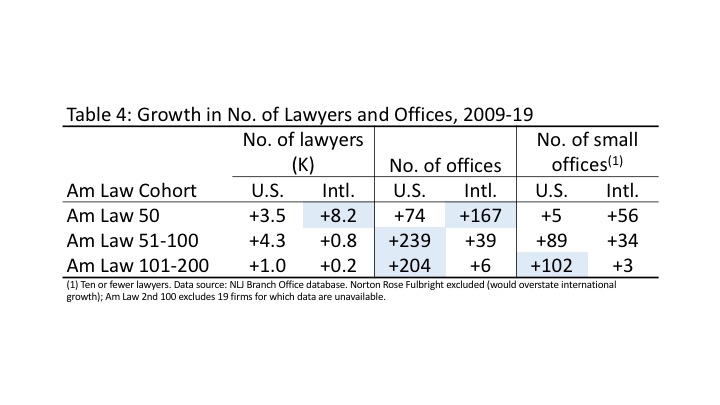

There are changes of the last decade that have weakened firms' ability to weather the coming downturn. For larger firms, it's been over expansion internationally—the Am Law 50 added over twice as many lawyers internationally as domestically and averaged over three new international offices each, see Table 4. We used to say the international markets were lower profit than the U.S. with the exception of London; given recent moves by Allen & Overy and Freshfields, this exception no longer applies. In addition, overseas lawyers are much harder to transition out (even as partners), so it takes longer to right size their numbers. The drain of transfer payments overseas, in combination with compensation systems biased toward global averages, will severely test the ability of firms to pay U.S.-based partners at the prevailing home-market rates.

For smaller firms the weakening change has been that, while they resisted the urge to grow overseas, they aggressively entered each other's domestic marketplaces. The Am Law second 50 added an average of almost five U.S. offices each; the Am Law second hundred added over 200 offices, half of which have 10 or fewer lawyers, again see Table 4. This has enhanced significantly the market power of clients, an edge that will be brought to bear in the form of intense pricing pressure in the months ahead.

So, what does this amount to in terms of pending job losses? Obviously, it varies significantly by firm. And we don't have a great handle on the aggregate effect. But, as an order of magnitude, if we repeated the same net 2008-10 contraction percent, and allowed for two new associate classes at smaller numbers than 2008-09, we'd be looking at a total of 20,000 departures—17,000 and 3,000 from the Am Law 100 and second hundred, respectively.

A closing thought: McKee Nelson were a powerhouse in structured finance and securitization. In 2007, as their markets melted down, they started shedding a lot of lawyers. To the surprise of Vault Law editors, the firm ranked number two in its 2008 'best to work for' associate survey. The editors went back to see if the survey pre-dated the cuts. It didn't. Rather, the McKee associates were commonly qualifying their survey responses with "in spite of the layoffs…" and would then go on to praise the partners, training, and culture. It's a salutary tale. We would do well to be like McKee in the months ahead.

Hugh A. Simons is formerly a senior partner and executive committee member at The Boston Consulting Group and chief operating officer and policy committee member at Ropes & Gray. Early retired, he now researches and writes about the business side of law firms and does some consulting for old friends. He encourages reader reactions at [email protected]

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Three Akin Sports Lawyers Jump to Employment Firm Littler Mendelson

Brownstein Adds Former Interior Secretary, Offering 'Strategic Counsel' During New Trump Term

2 minute read

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Pa. High Court: Concrete Proof Not Needed to Weigh Grounds for Preliminary Injunction Order

- 2'Something Else Is Coming': DOGE Established, but With Limited Scope

- 3Polsinelli Picks Up Corporate Health Care Partner From Greenberg Traurig in LA

- 4Kirkland Lands in Phila., but Rate Pressure May Limit the High-Flying Firm's Growth Prospects

- 5Davis Wright Tremaine Turns to Gen AI To Teach Its Associates Legal Writing

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250