Down 15% Is the New Flat

How the Q2 economic dip may be followed by a structural shift in demand away from traditional firms—and how partners should prepare for it.

June 14, 2020 at 07:41 PM

8 minute read

Credit: Vintage Tone/Shutterstock.com

Credit: Vintage Tone/Shutterstock.com

Just as with the global financial crisis from a decade ago, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic will have two effects on law firm demand: a near-in contraction in response to slowed economic activity and a longer-term structural shift away from traditional outside counsel. The former will precipitate a Q1 to Q2 2020 drop in hours of 10 to 15 percent; the latter will delay Big Law regaining its pre-COVID level of demand until 2026; Mid Law may never fully recover. Partners who believe the requisite response to the ongoing recession is simply to ride it out should reevaluate: a new view of what it means to be a partner at an elite firm is required.

Near-in drop in demand

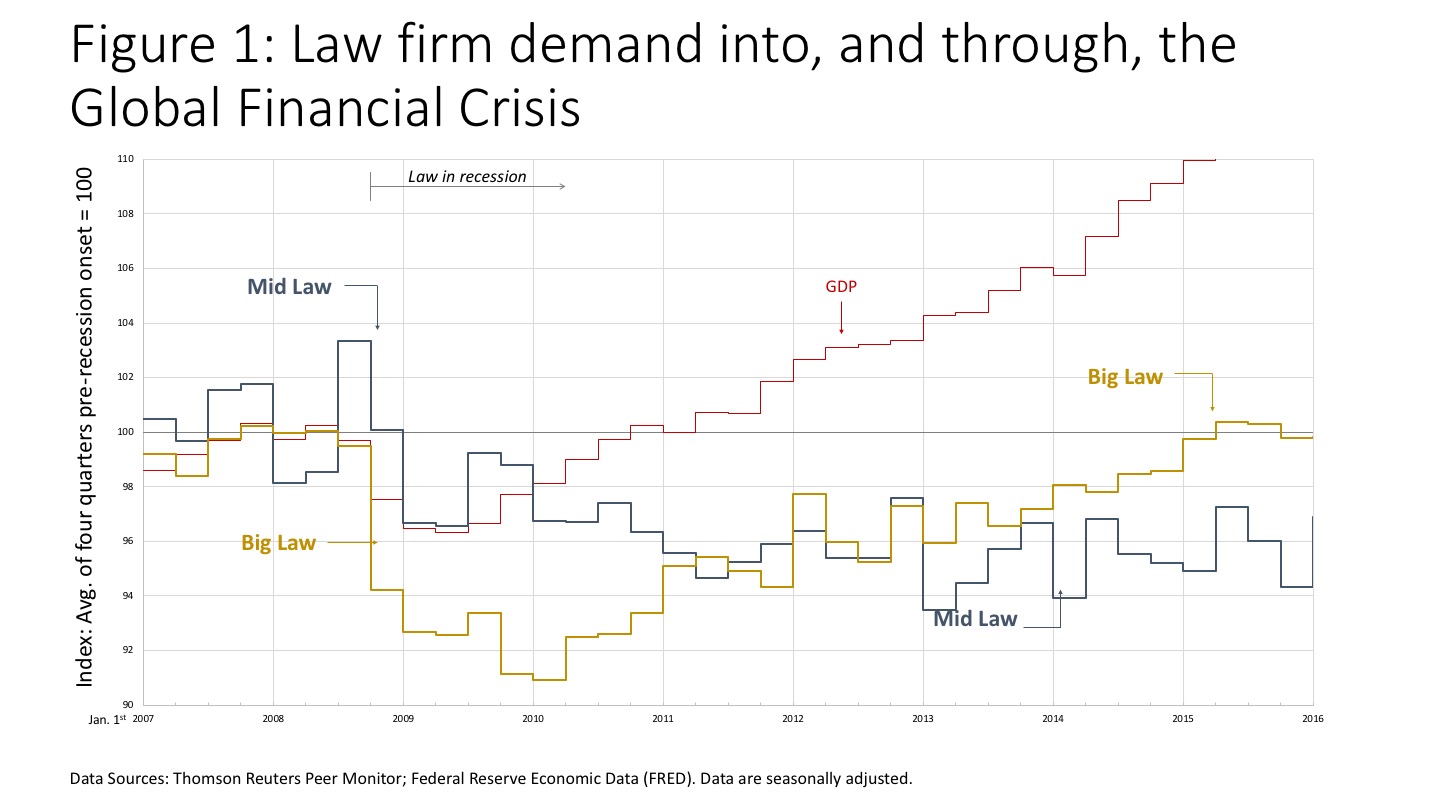

Let's start with a review of what happened to law firm demand at the onset of the global financial crisis. Figure 1 shows quarterly total hours for firms of two different sizes. The data are from Thomson Reuters Peer Monitor. The Big Law numbers are an average of a consistently-defined group of 33 Am Law 100 firms; the Mid Law numbers are for a consistent group of 34 Am Law Second Hundred and mid-sized firms. The level of broad economic activity is indicated by quarterly GDP.

GDP dropped markedly in Q4 of 2008 (following the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September) and continued to contract until mid-2009 with the trough being 4 percent below pre-drop levels. The timing of the near-in drop in Big Law demand mirrored that of GDP but the scale of the drop was 8 percent, twice that of GDP. In contrast, the near-in change in Mid Law demand fluctuated around the drop in GDP, with the scale of the contraction being the same as the 4 percent drop GDP. This difference reflects that the large transactions that make up a greater share of Big Law workflow dry up quickly on a recession's onset and, contrarily, that practices which grow at a recession's onset (labor and employment, renegotiation of contracts) comprise a greater share of Mid Law work.

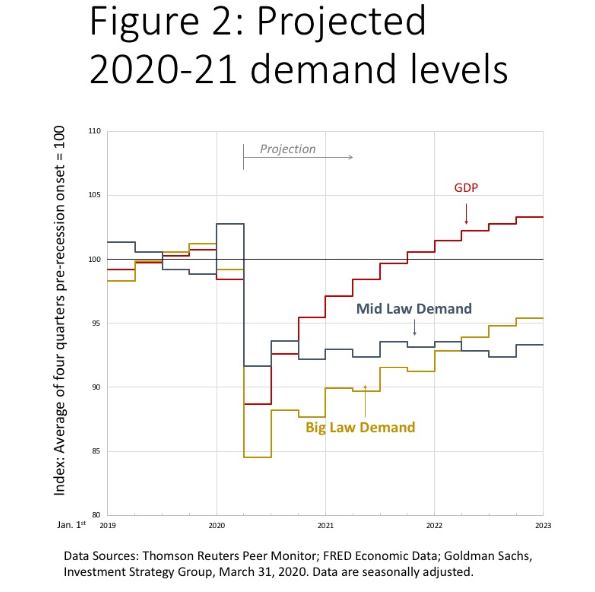

Figure 2 models what would happen to demand from Q2 2020 onward if the 2008-09 relationships between demand and economic activity were repeated. It starts with a recent Goldman Sachs forecast of GDP—a sharp drop in Q2 2020 followed by a gradual rebound. Big Law demand contracts by more than the contraction of GDP but returns to growth with a lag relative to the broader economy as it did in 2010-2016; Mid Law demand contracts to the same degree as GDP, fluctuates markedly, and (as in 2010-16) fails to regain its pre-drop level.

For the current quarter (Q2 2020), the model projects Mid Law and Big Law demand to be down from Q1 by 8 and 15 percent, respectively. These declines are sharper than many firms are expecting. A part of the disconnect is that there's wide variability across firms reflecting different practice mixes. Another reason is how the situation is evolving within the current quarter: Q1 momentum moderated the drop in economic activity in April, but May and June are each likely to be softer than the month prior. At law firms, we see this in the runoffs of ongoing matters. An analogous delay happens in the broader economy as is evident in the Atlanta Fed's GDPNow running estimate of Q2 GDP: on May 1st, Q2 GDP was projected to decline from Q1 at a 12 percent annual rate; by June 1st, the projected decline had increased to 53 percent. (Aside: by convention, GDP changes are quoted at an annual rate; actual quarter-to-quarter changes are one-fourth (compounded) of these percentages).

An 8 to 15 percent drop in demand from Q1 to Q2 is a sobering prospect. Its misery is mitigated by the widespread expectation of a rebound in Q3. But a note of caution here: while economists consider the end of a recession to be when growth rates change from negative to positive, for law firms the end is when the level of economic activity returns to its pre-recession level. This is not anticipated to be until late 2021.

Longer-term structural change

The history of the global financial crisis warns us not to presume law firm demand will simply follow the economy back to pre-recession levels. As Figure 1 shows, the economy started to recover in mid-2009 and regained its pre-recession level in the last quarter of 2010. Law firm demand, however, did not recover in parallel with the economy. It was not until early 2015, some four years behind the broader economy, that Big Law demand regained its pre-recession level; Mid Law has yet to regain its 2008 level.

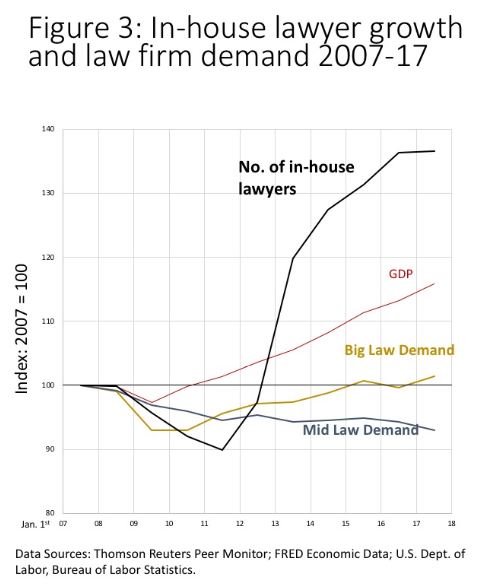

The driver of the disconnect between the level of economic activity and law firm demand was a structural change, precipitated by the recession, in how clients met their legal service needs. As Figure 3 shows, while law firm demand stalled, the number of in-house lawyers grew, indicating that clients took work away from outside counsel and did it in-house. Years of robust, compounding, billing rate increases had stoked law firm profits but had opened up an unsustainable gap between the cost of in-house lawyers and outside counsel.

Might we see some similar structural change in the wake of the current recession? On balance, you'd have to incline to yes. The options available to clients for a broad swath of their legal needs have grown significantly in the last decade—not just in number of providers (ALSPs, LPOs, the legacy accounting firms) but also in the reliability of such providers' services—many are now proven field-ready. This growth in number and prowess has shifted bargaining power in favor of clients and away from traditional law firms. Clients were uninclined to exercise their bargaining power during the economic froth of the last couple of years—they were focused on simply getting stuff done. The recession's arrival has spurred an urgency about cost reduction at a time when in-house lawyers have share-of-mind to dedicate to the task and the bargaining power to achieve it.

Structural changes come in waves with variations from wave to wave. We shouldn't expect the next wave in law to be a repeat of the growth of in-house counsel. As the viable service provider options for in-house legal departments have grown, their role will increasingly become that of traffic cops: triaging the needs of the business and channeling the work as appropriate to in-house lawyers, outside new-generation legal services providers, low-cost law firms, and traditional outside counsel. It's hard to see this as driving other than a decline in share for traditional firms.

Implications for partners

There are three dimensions to the law firm response. The first is the tried-and-true changes to the operating model: shed lawyers, raise rates, and increase leverage. This only works to a degree—it was, after all, persistence with the 'raise rates' portion that begat the ongoing structural changes.

Hence a second dimension: portfolio rationalization. It will be increasingly difficult for firms to operate profitably in market segments where they are not seen by clients as offering something compellingly different from that of other firms. Thus, it's not aggregate firm size that will determine sustainability and success, but depth in market segments and subsegments. Accordingly, firms should cut off their flailing growth initiatives and unremarkable flanker practices, and instead double down on where they're seen as truly distinct.

The third dimension is the most powerful: evolving to a higher-performance partnership.

Despite much progress, most partnerships today underachieve relative to their potential. Getting a partnership to perform to its fullest requires all partners to behave in ways that will be new to some: taking personal responsibility for their practices; acting as prime movers—not waiting for others to tell them what to do; being dogged, determined, and showing grit in the face of setbacks; being commercially driven; and, learning continuously through soliciting feedback from others. A new covenant needs to be forged among partners: we deliver relentlessly-excellent service for our clients; we are savvy about our firm as a business; and we are a mutually-committed elite team: we will go anywhere, do anything, at any time, to help a colleague of a client of the firm.

Joe Blackwood is a Senior Analyst at Thomson Reuters where he focuses on thought leadership analytics using Peer Monitor and other sources, to provide insight on the dynamics of the legal industry. He is contactable at [email protected]

Hugh A. Simons researches and writes about the business side of law firms. He is formerly a senior partner at The Boston Consulting Group and chief operating officer at Ropes & Gray. He welcomes reactions at [email protected]

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Law Firms Look to Gen Z for AI Skills, as 'Data Becomes the Oil of Legal'

Law Firms Expand Scope of Immigration Expertise Amid Blitz of Trump Orders

6 minute read

Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

5 minute read

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250