How GCs Struggle (And Succeed) After Retirement

“People treat it like they don't want to talk about it, like it doesn't happen,” said one retired GC. “If you're not thinking about this, you should be.”

August 27, 2018 at 01:18 PM

7 minute read

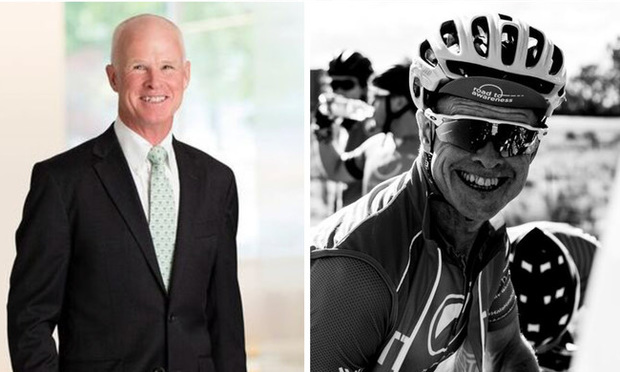

Ed Ryan, former GC of Marriott, before and after retirement. Courtesy photos

Ed Ryan, former GC of Marriott, before and after retirement. Courtesy photos

Jetting along in high-powered positions, top in-house lawyers can make the mistake of failing to prepare for the day when their landing gear drops for the last time. But what happens after that final flight? What is it like when the phone goes silent and the constant flow of emails slows to a trickle?

“It almost feels like it's a plane that has hit the runway and the thrusters are on and you come to a complete stop on that front of your life. Everything just stops,” said Ed Ryan, who retired last year as general counsel and executive vice president of Marriott International Inc. “When you leave a corporation, the door shuts pretty quickly behind you. Everything pretty much goes away. A lot of people are surprised by it.”

Retirement shock is due, at least in part, to a cultural tendency among GCs to ignore the Exit sign in the legal department as if it were a speck hovering far off on the horizon, more easily ignored than confronted, according to Ryan.

“People treat it like they don't want to talk about it, like it doesn't happen,” he said. “If you're not thinking about this, you should be.”

Former in-house leaders have certainly struggled to navigate through retirement. But in the process, they've also found some fulfilling—and in some cases very creative—ways to spend their time and even give back.

'No longer part of the money train'

Ryan, who spent 21 years in-house at Marriott, said that GCs who are standing on the precipice of retirement should prepare for their “work tribe” to essentially vanish. “You'll still have friends from work,” he said. “But that social circle, it's not around you anymore. And the people who are working, they're busy and you're not part of that.”

Marla Persky, who retired in 2013 as senior VP, GC and corporate secretary for pharmaceutical company Boehringer Ingelheim, said she knew it was time to stop when she realized she “no longer had the fire in the belly.” She was 58.

Other GCs lose their drive without knowing it and one day they get left behind as the company keeps flying forward—a fate that Persky was keen to sidestep: “I never wanted to be one of those people,” she said. “I was very lucky. I got to leave at my own time on my own terms.”

Perksy left, but she didn't slow down. She now works as a senior adviser at the consulting and recruitment firm BarkerGilmore and is CEO and president of WOMN LLC, which she co-founded in 2014 with the aim of helping women lawyers advance into executive roles and join the C-suite. The company offers mentorship and consulting services.

She said one piece of advice she'd give to retiring GCs who plan to go into business is to not “naively assume” that the outside law firms they'd worked with will morph into clients for their next venture. She'd thought that the “firms to which I'd given millions and millions of dollars of business during my career as a general counsel would reciprocate and hire me to help their women partners succeed.”

“But those firms that I gave the most business to didn't really have any use for me after I was no longer part of the money train,” she said.

Like many retired GCs, Persky also serves on nonprofit and for-profit boards. And she discovered a way to combine her love of food, travel and business by becoming the founder and CEO of Epicurean Travel, which puts together food-centric vacations for small groups seeking to “be immersed in the historical, cultural distinctiveness, and culinary delights of locations around the world.”

'I wasn't ready for retirement'

Having a “mosaic” of interests to pursue post retirement is key, said Ben Heineman, who spent 16 years as General Electric's senior VP and GC before he retired in 2005. Now, he teaches, writes and serves on several nonprofit boards.

“To me the biggest thing was freedom,” Heineman said. “I've been involved in big government, big law and big business for my whole career and I very much did not want to have clients calling me, CEOs calling me, meetings to go to. I wanted to be free.”

Freedom for Mike Dillon, who retired in July from his position as Adobe's top lawyer, the fourth GC post he'd held, meant baking sourdough bread, a lot of it—he said he made two loaves a day for the first three weeks after he left Adobe. Then Dillon turned to another passion: cycling. He'd already written a book about riding his bike across the country. Seeking a new adventure, he and his youngest son, a recent college grad, set off Aug. 8 to ride gravel bikes along a 2,768 mile trail that follows the Continental Divide between Canada and New Mexico.

Dillon also was part of a team behind a documentary film about climate change and the decline of sea ice.

“Just enjoy life. You really need to have a demarcation, a way of decompressing from decades in corporate culture,” he advised. At the same time, he cautioned, “Before you make that decision [to retire] put together a list of everything in the world you'd like to do so you're not just watching daytime TV and eating too much.”

Michael Callahan, who left his role at LinkedIn earlier this year, agreed. The former GC, who now runs Stanford Law School's Rock Center for Corporate Governance, said GCs who are considering retirement or a career change should “take the time and be intentional about the work” they want to do and talk with people who are doing that work.

“I wasn't ready for retirement,” said Callahan. The 50-year-old had been a GC for about 15 years, first at Yahoo and then at Auction.com, now Ten-X.com, before joining LinkedIn about four years ago. “I certainly thought about the transition for some time and felt like throwing myself into a new challenge, which has been rewarding.”

'Certain amount of impostor syndrome'

For some GCs, including Mark LeHocky, who served as the head lawyer for Ross Stores, Inc. and Dreyer's Grand Ice Cream, Inc., walking away from the legal department was relatively easy. LeHocky had been doing pro bono mediation work on the side for years before he retired and became a full-time mediator. He's also teaching at UC Berkeley's Haas School of Business.

“It was seamless,” LeHocky said of leaving the GC life.

But he might be an exception. Jay Mitchell, the former chief corporate counsel at Levi Strauss & Co. and now a professor at Stanford Law School, said he was both “thrilled and terrified” when he left the in-house world. And he described the first couple of years as being “pretty rough.”

“There was a certain amount of impostor syndrome,” he said of entering academia. But he added, “In many ways, people who work in-house, and particularly general counsel, bring a lot of value to teaching inside a law school. You've seen things from a broader perspective than one gets at a law firm.”

While Ryan, the retired Marriott GC, has seen colleagues struggle in retirement, he said he's not had much difficulty adjusting.

“It's daunting if you define yourself by what you're doing with your work or your title,” Ryan said. “I was fortunate because I never really defined myself that way. But I think there's a natural tendency to do that.”

Like Dillon, the ex-Adobe GC, Ryan is a longtime cyclist. He said he'd been biking “off and on” while he was a GC—but in retirement, he was able to go all in. He recently spent a week riding in South Africa. Before that he was cycling in Spain. And now he's planning to bike from Pittsburgh to Washington, D.C.

“The decision you've got to make is, 'Am I really going to retire?'” he said. “Make that decision and don't go half-ass on it.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Exits Leave American Airlines, SiriusXM, Spotify Searching for New Legal Chiefs

2 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250