(Photo: Shutterstock)

(Photo: Shutterstock)Is Litigation Financing the Next Big Thing for Legal Departments?

Law firms have warmed to the idea of litigation finance in recent years, but studies show that a majority of in-house lawyers still have not.

December 10, 2018 at 03:34 PM

8 minute read

When legal funders look at the corporate world, they see a vast, untapped market of potential clients. Over the last few years, funders have seen law firms climb aboard the increasingly powerful litigation finance train. Now, they want the in-house crowd to follow.

Litigation finance firms invest in litigation in exchange for a cut of the settlement or award. They can also enter the picture toward the end of a case and provide a cash infusion to help companies and law firms enforce judgments. They tout litigation financing as a way for firms and companies to hedge risks and control costs.

But a pair of recent studies this year suggest that many legal departments are hesitant.

Burford Capital, a top global player in the world of legal finance with offices in New York, Chicago, London, Singapore and Sydney, surveyed 177 in-house lawyers in the U.S., U.K. and Australia and found that only 5 percent said their organization had used litigation finance.

Another lit funder, Lake Whillans Litigation Finance LLC in New York, partnered with Above the Law, a legal news website, to carry out a similar study and discovered that 74 percent of the 276 in-house lawyers in 37 cities in the U.S. who responded said they had no firsthand experience working with a litigation finance firm.

More than 30 percent of those same lawyers said they wouldn't even consider using litigation finance. Among them, the most common reason given was “ethical reservations,” followed by a negative perception of lit finance based on what they'd heard from others.

Litigation finance has encountered opposition related, at least in part, to ethical concerns. Earlier this year, the New York City Bar Association released a formal opinion in which it held that litigation finance agreements violated the rule that prohibits lawyers from sharing fees with non-lawyers.

“Rightly or wrongly, the rule presupposes that when non-lawyers have a stake in legal fees from particular matters, they have an incentive or ability to improperly influence the lawyer,” the opinion stated.

The practice also has drawn fire from the defense bar and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which has called for a nationwide disclosure rule that would lift the veil on the details of litigation finance agreements and reveal the identities of the funders. But the effort has been unsuccessful so far.

Lisa Rickard, president of the U.S. Chamber Institute for Legal Reform, wrote in a June 2017 letter that not having a disclosure rule lets funders “continue to operate in the shadows, concealing from the court and other parties in each case the identity of what is effectively a real party in interest that may be steering a plaintiff's litigation strategy and settlement decisions.”

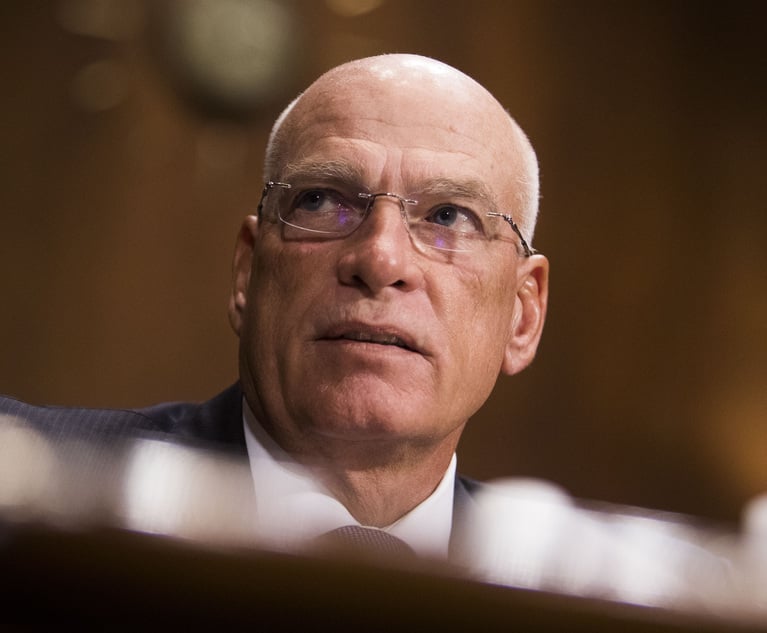

Boaz Weinstein

Boaz Weinstein

But Boaz Weinstein, a principal at Lake Whillans, said that “a long time ago lawyers [at law firms that have warmed to lit fin] would have cited some of the same issues.” He continued, “they [in-house counsel] don't understand this fully, so their knee-jerk reaction is that mixing money with litigation is bad. But what we've found is often people come in saying that they think they'd have ethical concerns and end up walking away very much turned around.”

|Concerns about control persist.

Weinstein believed that some in-house lawyers are leery of litigation financing because they fear that funders will try to steer the course of the litigation in which they have invested. But funders stress that this is a misperception and they typically do not control the litigation or its resolution.

“It would be a rarity for a litigation funder to have control over the outcome of a proceeding,” he said. “When we are financing a case it's the claim holder's case. They make the calls on strategy and settlement—all the tactical issues.”

Another potential factor behind its apparent failure to catch on with in-house lawyers is that companies tend to pay for their own litigation, according to Susan Hackett, CEO of law department consulting firm Legal Executive Leadership in Chevy Chase, Maryland.

Hackett said it's primarily law “firms that have an interest in litigation funding, especially when they're working on cases that are class actions or that otherwise require an investment by the firms in order to put together a case that will return their money.”

|Survey shows rising interest levels.

David Perla

David Perla

But David Perla, managing director at Burford, which struck a $45 million deal with British Telecom in 2016, sees the tide changing. He cited the aforementioned Burford study's finding that nearly half of in-house lawyers reported that they intended to use litigation financing in the next two years.

As more law firms have used litigation finance, they've begun to trumpet the benefits to legal departments, according to Perla and Weinstein. Funders sometimes join up with law firms when they pitch lit fin to legal departments. Funders also are using technology to court clients.

Burford's underwriting team uses an eight-point probability weighted financial model to help determine whether to invest in a case and at what price. It also uses software to comb through public databases to assess risks. But an investment committee ultimately makes the final decision, according to Perla.

“We use a host of technologies to help us identify cases that might be interested in funding. It helps our teams around the world determine which clients to talk to … slice and dice what he right types of claimants might be,” he said.

With funders ramping up outreach efforts, it's likely that legal departments are slowly becoming more aware of the pros of litigation finance, which can give companies the ability to shift litigation risks to third-party funders.

In the Lake Whillans/ATL survey, among those in-house lawyers who had used litigation funding in the past, 72 percent said they would do so again.

Lit funding also allows companies to move litigation costs off balance sheets and avoid immediate dings to the bottom line that could drag down profits.

“When you litigate, the cost of that is an ordinary expense and it hits your earnings immediately. And if and when you win the award, to the extent that you recover that money, it doesn't count as normal top line revenue. It falls below the line, which CFOs hate,” Perla said.

Weinstein agreed, saying that the bottom-line factor was a “huge driver, especially when you're talking about bigger corporations and publicly traded corporations.”

|Leaving behind millions of dollars.

Money is always a powerful motivator. And yet companies appear to be walking away from millions of dollars because they're unwilling to take on the cost and risk of litigation, Perla said.

According to Burford's survey, 68 percent of in-house respondents said they had walked away from a claim because they were concerned about hurting their company's bottom line. And 59 percent reported leaving on the table uncollected or unenforced judgments valued at $10 million or more.

“They're not spending the money to collect or enforce judgments,” Perla said. He added that the main factor in-house leaders should weigh when eyeing litigation finance is whether it's worth their while.

“The question for a GC or head of litigation is always whether this is the best use of her time,” he said. “Is her portfolio of litigation such that it's worth the investment or time to consider this? What were getting better at is finding the corporations that are more likely to consider it.”

Read more:

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

GC Pleads Guilty to Embezzling $7.4 Million From 3 Banks

GC With Deep GM Experience Takes Legal Reins of Power Management Giant

2 minute read

US Reviewer of Foreign Transactions Sees More Political, Policy Influence, Say Observers

'Unlawful Release'?: Judge Grants Preliminary Injunction in NASCAR Antitrust Lawsuit

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Hochul Vetoes 'Grieving Families' Bill, Faulting a Lack of Changes to Suit Her Concerns

- 2Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Customers: Developments on ‘Conquesting’ from the Ninth Circuit

- 3Biden commutes sentences for 37 of 40 federal death row inmates, including two convicted of California murders

- 4Avoiding Franchisor Failures: Be Cautious and Do Your Research

- 5De-Mystifying the Ethics of the Attorney Transition Process, Part 1

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250