FCPA Corporate Enforcement Slowdown in the Current Administration? What Slowdown?

The tea-leaf readers and wishful thinkers have been predicting an FCPA corporate enforcement slowdown for years. Prior to 2015, sentiment was, in effect, that FCPA enforcement had enjoyed a long run, but all “good” things must come to an end.

February 01, 2019 at 03:45 PM

6 minute read

The tea-leaf readers and wishful thinkers have been predicting an FCPA corporate enforcement slowdown for years. Prior to 2015, sentiment was, in effect, that FCPA enforcement had enjoyed a long run, but all “good” things must come to an end. In 2015, when there were relatively few corporate investigations, pundits were convinced that the slowdown was upon us—until 2016's record year of enforcement actions (DOJ and SEC). Then, with the possibility of a more business-friendly U.S. administration in 2017, we heard the familiar refrain of a slowdown. Those views were seemingly reinforced in the early months of the new administration, when FCPA enforcement started slowly. Then, the FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy (the policy) was instituted, offering a presumption of declination for companies who meet the Policy's requirements. With companies obtaining declinations, and DOJ resources being consumed (by the increased emphasis in the prosecution of individual FCPA violators, who are generally more likely to challenge the government's case in court and tie up FCPA unit resources) as well as shifted to other administration focuses, the view was that these factors likely equated with less pressure on companies regarding anti-corruption compliance.

Unfortunately, the continued anticipation of the demise of FCPA enforcement has been and remains premature. The prosecutors and leadership at the fraud section and the FCPA unit are not politically appointed, and they have made clear at numerous conferences that they are very hard at work building cases, including cases against companies.

Even under the policy, the argument for easing up on anti-corruption compliance falls flat. In order to qualify for a declination, companies must first self-report—which means they have to detect the violation before the DOJ learns about it from a variety of other sources, including: generally increasing FCPA whistleblower reports, the increasing detection capabilities resulting from the substantially increased resources of the FBI international corruption squads, and tips from foreign law enforcement, who are increasingly active in the anti-corruption space (more on that below) and—in many instances—developing stronger relations with U.S. law enforcement.

Moreover, companies able to secure declinations must still engage in a properly scoped internal investigation, provide full cooperation and thoroughly remediate, the costs of which are often quite substantial. Companies receiving declinations also face mandatory disgorgement of any profits, along with potential SEC enforcement action and the increasing risk of one or more foreign enforcement actions, making a declination, at times, somewhat of a pyrrhic victory. Thus, prevention, even more than mere detection, is arguably as important as ever. All this translates into a continued need to invest in an effective compliance program.

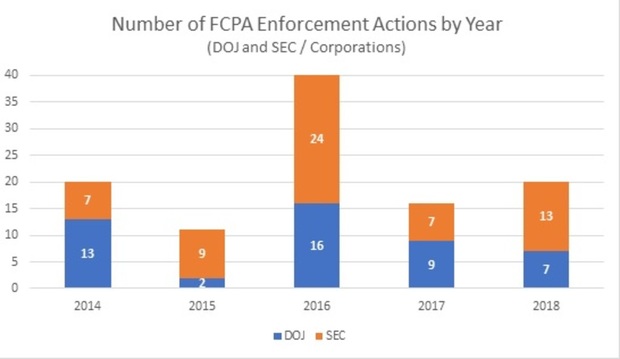

Almost two years into this administration, the numbers bear out our theory. Recognizing 2016 as an outlier, if you average out 2015 and 2016, the total number of corporations facing FCPA enforcement actions remains relatively consistent over the last five years.

Figure 1: Number of FCPA Corporate Enforcement Actions by year (DOJ and SEC).

Sources: Stanford Law School FCPA Clearinghouse Statistics and Analytics; SEC Enforcement Actions: FCPA Cases; and US DOJ Fraud Section-FCPA Related Enforcement Actions

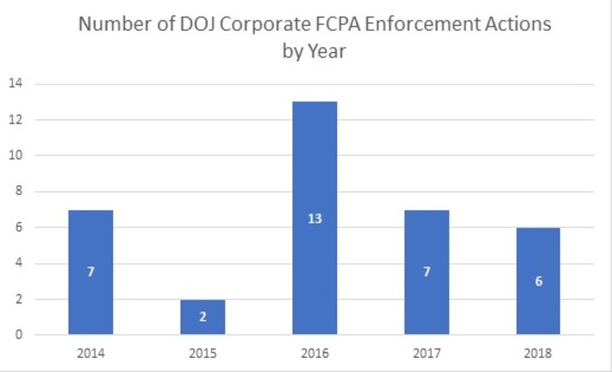

Furthermore, these numbers are—in some ways—misleading, because a DOJ enforcement action against a parent and multiple subsidiaries are treated in these figures as multiple enforcement actions against separate companies. But when a multinational considers the risk of an FCPA enforcement action, arguably a single resolution or multiple resolutions within the same corporate enterprise reflects the same risk—the risk that the DOJ (or SEC) turns its attention to your company. When one treats such multiple actions as a single, consolidated enforcement action, and you average 2015 and 2016 across the two years, it is evident that the DOJ corporate enforcement has been relatively consistent over the past five years.

Figure 2: Number of DOJ FCPA Corporate Enforcement Actions by year—consolidating multiple enforcement actions against separate companies within one parent company as a single action against said parent.

Sources: Stanford Law School FCPA Clearinghouse Statistics and Analytics; US DOJ Fraud Section-FCPA Related Enforcement Actions.

Furthermore, when one also factors in declinations and cases closed without action, it becomes clear that any theory that the DOJ is less active—even against corporations—falls apart. See Figure 3. Since the start of the pilot program in 2016, the total number of cases where the DOJ closed the case or declined under the pilot program or the policy has increased substantially, from seven, to nine, to 17 in 2018. While those companies escaped a DOJ enforcement action, they all faced the substantial costs and pressure associated with being under DOJ investigation. Combining these figures (enforcement actions, declinations, and closings without action), the total number of multinationals facing and resolving DOJ or SEC investigations for FCPA violations has not decreased in the past few years.

Figure 3: DOJ declinations versus closed investigations  Sources: US DOJ Fraud Section–Declinations; www.fcpatracker.com

Sources: US DOJ Fraud Section–Declinations; www.fcpatracker.com

Lastly, one must also factor in the increased risk of foreign law enforcement scrutiny. According to Trace International's 2017 Global Enforcement Report, and perhaps for the first time, the number of active foreign bribery investigations outside the United States is greater than the number of investigations by the United States.

In fact, in 2017, European law enforcement alone had more investigations (118) than the United States (114), at least of the 261 investigations reported. And these figures do not include the corresponding investigations into domestic corruption by foreign companies, which is why active enforcers such as Brazil are not listed in the Trace Report. Factoring in to the calculation the substantial increase of anti-corruption investigations by foreign authorities, the case for continued vigilance becomes clearer.

Conclusion

When one objectively considers the total DOJ, SEC and foreign law enforcement activity in the foreign bribery space, it is clear that the risk that companies find themselves under scrutiny for such violations has not diminished. When one also considers the requirements for securing a declination under the policy, the benefits to a robust compliance program remain as important as ever.

Matt Queler is a Deloitte risk and financial advisory principal in Deloitte Financial Advisory Services, where he assists law firms and companies with internal investigations, the FCPA, fraud, and other white collar matters before the DOJ, SEC and foreign authorities. He also helps clients improve their compliance programs, conduct pre-M&A and third-party due diligence, and tackle post-deal integration.

Michael Won is a Deloitte risk and financial advisory manager where he assists clients with their compliance needs related to regulatory healthcare and anti-corruption anti-bribery (i.e., FCPA) matters using technology solutions and providing risk and compliance assessments and assistance with internal investigations.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

AI Disclosures Under the Spotlight: SEC Expectations for Year-End Filings

5 minute read

A Blueprint for Targeted Enhancements to Corporate Compliance Programs

7 minute read

Three Legal Technology Trends That Can Maximize Legal Team Efficiency and Productivity

Trending Stories

- 1New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 2No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 3Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 4Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

- 5Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250