Recognizing and Remediating Gender Pay Equity Issues in the Workplace: Part I

The #MeToo movement has compelled employers to take a harder look at their workplace policies and practices and to ensure appropriate workplace behavior among their employee ranks.

April 10, 2019 at 02:15 PM

6 minute read

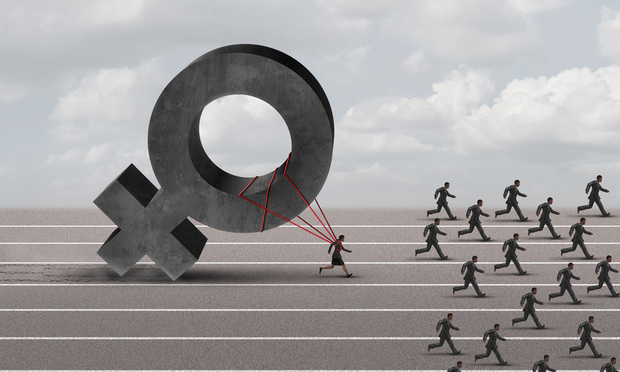

The #MeToo movement has compelled employers to take a harder look at their workplace policies and practices and to ensure appropriate workplace behavior among their employee ranks. While the specific issue of sexual harassment has garnered the bulk of the headlines, potential pay gaps between men and women are equally deserving of attention and remediation even when, as is often the case, it is simply an inadvertent consequence of a legitimate pay practice. In this three-part series, Brian Murphy and Jonathan Stoler will provide employers with the tools to identify gender inequities in compensation and offer strategies for resolving them prospectively. Part I will focus on the historical context and current legislative landscape informing employer approaches to pay equity concerns. Part II will introduce employers to pay equity audits as a tool for addressing compensation disparities. And Part III will offer employers tips for implementing remediation efforts and adjusting practices to ensure future compliance.

Part I: The Historical and Legislative Context Informing Pay Equity Efforts

Congress enacted the Equal Pay Act of 1963 as an amendment to the Fair Labor Standards Act for the specific purpose of “prohibiting discrimination on account of sex in the payment of wages by employers.” The EPA was enacted one year earlier than Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, perhaps highlighting the gravity with which Congress viewed the issue. Indeed, at the time of the EPA's enactment, Congress expressed that wage differentials depressed wages, prevented the maximum utilization of labor resources, contributed to labor disputes, burdened commerce, and constituted an unfair method of competition. Eradication of the wage gap was described as “a most worthy national policy.”

The EPA did not, of course, prohibit all pay differentials among members of the opposite sex. It prohibited differentials among men and women in an “establishment” for “equal work on jobs the performance of which requires equal skill, effort, and responsibility, and which are performed under similar working conditions.” It also allowed for pay differentials attributable to seniority systems, merits systems, quantity/quality of production systems, or “any other factor other than sex.”

The EPA has dramatically assisted in rectifying the issue. In 1979, the first year for which comparable earnings data is available, the earnings for female full-time wage and salary workers were 62 percent of those for men. As of 2017, the gap has lessened such that women earned 80.5 percent of that earned by men. The differentials vary from this mean from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, industry to industry, job classification to job classification, and across other demographic markers. On the whole, however, federal, state and local governments have resoundingly concluded that the disparity remains too great and legislative efforts have begun with renewed energy.

At the federal level, the Paycheck Fairness Act (PFA) is currently pending before Congress. As currently drafted, the bill would eliminate the allowance for wage differentials based on “any other factor other than sex,” and limit the exception to bona fide factors, such as education, training or experience. The bill would also impose greater prohibitions on retaliation and strengthen enforcement mechanisms, among other requirements. Various iterations of the PFA have been introduced, and tabled, in Congress since 1997 and given the current administration, there is mild optimism, at best, that it will be enacted into law. It did, however, pass the House on March 27, by a 242-187 vote largely along party lines.

State governments have thus increasingly joined the fray to bridge the gaps in federal legislation by resort to a variety of approaches. Some states have sought to strengthen their EPA analogues by adopting a similar approach to the PFA, limiting the potential defenses to pay equity claims. For example, some states have eliminated the concept of “equal work” in favor of “substantially similar” or “comparable” work, or relaxed the “same establishment” requirement to allow for comparisons across a broader swath of locations, such as a county or an entire state.

Other states have approached the matter from a different angle, proposing laws to promote pay transparency by banning discrimination or retaliation against employees who discuss their wages. These states believe that policies which shroud pay practices among a workforce allow pay differentials to perpetuate, if not proliferate. These laws do not go so far as the Gender Pay Reporting regulations in effect in Great Britain or the EEO-1 pay data reporting obligations applicable to certain federal contractors and large employers, but are generally borne from the same principle.

A number of states and local governments have attacked the issue by stemming the influence of historically inequitable pay decisions. These laws prohibit employers from using past salary information, or even inquiring about a new employee's past salary, for purposes of setting a new salary. This approach is premised on the theory that a prior compensation decision may have been infected by discrimination such that using it as a benchmark for future salary decisions perpetuates, even unintentionally, prior discrimination in wages.

Lastly, some states have provided employers with specialized defenses in litigation where they have themselves undertaken efforts to eliminate pay gaps and have made “reasonable progress” toward attaining that goal. These laws allow for an employer to defend against compensatory or punitive damages, for example, or allow for an affirmative defense to liability altogether, where employers have conducted audits designed to identify and resolve pay inequities among their workforces.

Employers, particularly those operating in multiple jurisdictions, are thus faced with navigating a quagmire of existing and potential hurdles. Importantly, these laws do not require that unlawful pay gaps be the result of intentional discrimination. Thus, rather than assuming a reactive posture, employers are best served to engage proactively and take the necessary steps to eliminate any existing pay inequities to effectively immunize themselves from these laws, whatever their form. Part II will examine the utility of pay audits as a tool for meeting this goal.

Brian D. Murphy and Jonathan Stoler are partners in the labor & employment practice group at Sheppard, Mullin, Richter & Hampton LLP in New York.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

AI Disclosures Under the Spotlight: SEC Expectations for Year-End Filings

5 minute read

A Blueprint for Targeted Enhancements to Corporate Compliance Programs

7 minute read

Three Legal Technology Trends That Can Maximize Legal Team Efficiency and Productivity

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250