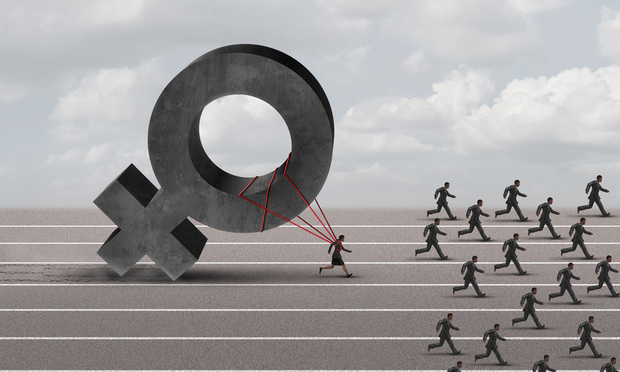

Pay Equity Audits as a Risk Identification Tool: Part II

Employers faced with navigating the wave of new and potential legislation directed at remediating pay equity issues would be wise to proactively to address the issue.

April 11, 2019 at 11:09 AM

5 minute read

Pay-Equity

Pay-EquityEmployers faced with navigating the wave of new and potential legislation directed at remediating pay equity issues would be wise to proactively to address the issue. While it may seem obvious, none of the applicable laws prohibit pay differentials outright; instead, all laws prohibit pay differentials only when they are attributable to impermissible factors. A properly structured pay equity audit can serve to identify only those differentials that are potentially unlawful, and tacitly approve of those differentials that are permissible.

Each employer may have different goals for an audit, different ideas concerning the appropriate focus of the audit, and different resources to be contributed to the audit, all of which prevent a “one size fits all” approach to describing an audit. Nevertheless, five features will be integral across all efforts.

First, and perhaps most critical, is a planning and strategy session during which the employer and inside or outside legal counsel can map the audit. It will be critical for the auditor to gain an understanding of the employer's business as a general matter, and as a specific matter, any unique considerations relevant to the employer's compensation systems, practices and philosophies. Are advanced degrees, for instance, prioritized over length of service? Does the employer favor a lockstep compensation approach over a merit-based system? Answers to these questions will be necessary to identify pay differentials that deviate from expected results and which may, therefore, be areas of concern.

In addition to these contextual and ideological matters, the planning session will allow the employer and the auditor to set the scope of the audit, whether it be companywide, a division thereof, or a lone job title. The planning session will also serve to identify points of contact at the employer organization who will partner with the auditor, and allow the parties to set a budget, timeline, and schedule for updates. The meeting will also allow for a discussion of how best to conduct the audit under the protection of the attorney-client privilege.

Second, is gathering the data. An effective audit that accounts both for compensation differentials as well as controls and other potential explanations for any inequities requires both “hard” and “soft” data. Hard data will consist of the specific compensation data that will allow the auditor to capture the total earnings of a given employee over a predetermined timeframe. Thus, the hourly wages, overtime wages, and hours worked, in the case of nonexempt employees, and base salary, in the case of exempt employees or salaried nonexempt employees, will be necessary. Discretionary and non-discretionary bonuses, equity awards, grants, and dividends and other forms of supplemental compensation will be necessary as well. “Soft” data will consist of information that will paint the picture of each employee. Age, years of service, business unit or department, functional and corporate titles, location, and, of course, gender or other demographic to be analyzed as part of the audit. The integrity of this process is paramount as the adage “garbage in, garbage out” applies firmly.

Third, is the preliminary analysis of the compensation data among properly comparable groups. Identification of the right persons for comparison will be informed by both logical considerations as well as the legal requirements for the jurisdiction within which the audit is performed. As to the former, in a law firm for example, little purpose would be served in evaluating the compensation of paralegals versus attorneys. Instead, the comparison must be among persons doing similar work based on skill effort or accountability. As to the latter, federal law suggests that the comparison be limited to workers in a single establishment, whereas some states, like California, require consideration of workers (performing functionally similar roles) across the entire state. Whatever grouping the employer and auditor determine is appropriate, the goal of the analysis at this stage is the same: identification of any pay gaps that are not random and are statistically significant under generally accepted statistical models such that further investigation is warranted.

Fourth, as to these “hot spots,” the employer and auditor must work together to identify any objective, nongender-based (or other demographic) factors that legitimately account for the identified pay differentials. Length of service may be fully explanatory for one employer, whereas another, such as a software development company that has a particularly young workforce, may not consider it all such that it does not account for the differential. Other potential explanatory factors, but by no means exhaustive, include location, education, years of experience, production targets, performance evaluations, or grade. Interviews with supervisors may also be necessary to understand nuances between the roles of two employees who work in the same location and share the same duties who are, otherwise, ostensibly comparable.

These efforts should narrow the number of employees (or job functions) for which pay disparities exist that are not explainable by nongender-based criteria. These remaining groups will likely warrant remediation measures, the fifth and final feature of a pay equity audit, which will be discussed in Part III of this series.

Brian D. Murphy and Jonathan Stoler are partners in the labor & employment practice group at Sheppard, Mullin, Richter & Hampton LLP in New York.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

AI Disclosures Under the Spotlight: SEC Expectations for Year-End Filings

5 minute read

A Blueprint for Targeted Enhancements to Corporate Compliance Programs

7 minute read

Three Legal Technology Trends That Can Maximize Legal Team Efficiency and Productivity

Trending Stories

- 1Arguing Class Actions: With Friends Like These...

- 2How Some Elite Law Firms Are Growing Equity Partner Ranks Faster Than Others

- 3Fried Frank Partner Leaves for Paul Hastings to Start Tech Transactions Practice

- 4Stradley Ronon Welcomes Insurance Team From Mintz

- 5Weil Adds Acting Director of SEC Enforcement, Continuing Government Hiring Streak

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250