Becoming A Business Leader

For general counsel, legal risks aren't the only factor. Gaining a seat at the table means learning the business and bringing solutions rather than a blanket 'no.'

April 30, 2019 at 12:00 PM

9 minute read

(photo: Shutterstock.com)

(photo: Shutterstock.com)

The general counsel role is increasingly not just a legal one.

In 2019, it's a business one, too. As legal departments grow, implement legal operations teams and stick to strict budgets, general counsel are expected to bring an economic edge to the top lawyer spot.

That's not exactly a skill taught in law school. But Corporate Counsel spoke with eight former company general counsel to find out how in-house hopefuls can develop the skills they need for success, as part of a Law.com podcast series, “GC Speak.”

➤ RELATED PODCAST: Here's What It Really Takes to Make It as a GC

One general counsel, the former top lawyer at Apple and Oracle, Dan Cooperman, managed to gain some business acumen before his leap in-house. During law school, Cooperman earned a Master of Business Administration alongside his juris doctor.

“You had to make budget, you had to do personnel reviews … you need to be able to communicate well up the ladder [and] down the ladder. All these things were really the skills one would learn about in an MBA program,” Cooperman said. “So I felt that was very, very helpful.”

Paul Williams, the former general counsel of Cardinal Health, said not earning an MBA before moving in-house is “one of the few regrets” of his in-house career.

Most general counsel didn't get an educational head start on business skills. They learned on the job—or at least on a job. Both Marla Persky, the former general counsel of pharmaceutical company Boehringer Ingelheim, and Stasia Kelly, who led the legal team at Sears, Fannie Mae and American International Group, worked at corporations in nonlegal roles before law schools. Neither entered their corporate jobs with the intention of using it to build in-house experience. But for Persky, at least, her time working in Colgate-Palmolive's marketing department helped her gain cred later as a company lawyer.

“Because I walked in their shoes, I understood how complicated it is to do those roles when you're part of a very large organization,” Persky said.

She built on those skills during her time in-house at both Boehringer Ingelheim and Baxter International Inc., her first legal department role. During her time at Baxter, Persky joined groups that had nothing to do with legal but, because she was hardworking and understood the business, company leaders found she still added value “beyond being 'just' the lawyer.” At one point, Persky even took on a nonlegal leadership role, managing a recently acquired Baxter subsidiary.

Daniel Cooperman, DLA Piper partner

Daniel Cooperman, DLA Piper partnerOther general counsel moved in-house with no experience at a company, legal department or otherwise, joining from the Department of Justice after years at a firm. They still found success in the general counsel seat, with some business lessons learned along the way.

Doug Melamed, the former general counsel of Intel Corp., said he spoke with board members and executives to learn about the company prior to the role, an attempt to get as far up the “steep learning curve” for his in-house transition. Even with that extra effort, he said he learned the most about being a business partner and in-house lawyer on the job.

One of those lessons: Don't worry about knowing every aspect of the law—but learn every aspect of the business. While in-house, Melamed found that offering legal advice that was too risk-averse or didn't provide an alternate solution was a quick way to be discredited. It's a lesson he drilled into all Intel lawyers.

“The word 'no' should be part of the active vocabulary of every Intel lawyer. But then I went on to say that it's easy to say no, you read the law, you say, 'Gee, there's a legal risk here, don't do it.' What you really want to do is say, 'No, but …'” Melamed said. “You want to say, 'No, you really can't do it that way, but here's a way that is 80 percent or 90 percent of what you want as a business matter with significantly reduced legal risk.'”

Stasia Kelly, Managing Partner (Americas) with DLA Piper in Washington, D.C. February 26, 2019.

Stasia Kelly, Managing Partner (Americas) with DLA Piper in Washington, D.C. February 26, 2019.It's a sentiment echoed by Kelly and former Allstate Corp. general counsel Michele Coleman Mayes, who said offering solution-based answers helped them gain a seat at the business decisions table. Which, Kelly noted, is a good place for lawyers to be.

If general counsel are trusted “shape stuff from the very beginning,” she said it's less likely they'll have to deliver that uncomfortable “no” to an unreceptive audience after a product or service is more fleshed out—think “compliance by design.” But the invite to a product-building table isn't a given, Kelly said. During her time in-house, she had to earn her status as a business partner by proposing strong ideas and, again, finding solutions.

Mayes noted that can be an initial challenge for in-house counsel. Their status as both a lawyer, with a background of risk-aversion, and a businessperson can cause “tension.” At the start of her in-house career, Mayes said she often leaned on her legal degree, shutting down risky ideas and focusing more on her status as a lawyer.

While that legal background is key, Mayes said general counsel who “pull rank” when it comes to business decisions that involve risk, relying on their law degree without incorporating business acumen, will find themselves kicked out of the room.

“If the system sees you as a foreign object, it's like any system—it will try to reject you. And you don't want to be excluded from meetings or someone they try to work around, because that defeats the whole purpose of you having the opportunity to participate and have your voice heard, if they're going to avoid you at all costs,” Mayes said.

In-house leaders who have found success as a business partner at one company, or even in one project at the same department, will have to recalibrate with each new role or challenge, lawyers said. Williams, who was general counsel of small tech startup Information Dimensions and in-house at Borden Inc. before joining Cardinal Health, said every company has different legal needs and risk appetites.

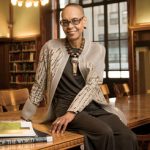

Michele Coleman Mayes, general counsel at the New York Public Library

Michele Coleman Mayes, general counsel at the New York Public LibrarySmall tech startups' general counsel need to take more risks than established corporations—they're entering new markets with innovative ideas that might not yet have regulatory clarity, he said. Applying that same framework to a large company in a tightly regulated industry might not go so well.

“What I learned was that each business requires its own legal calibration,” Williams said. So general counsel looking to reach business partner status need to be solutions-focused and industry- and company-specific. Their advice also need to be timely, Cooperman said.

He and Melamed noted the change in pace when they moved in-house, as well as culture. When Cooperman moved in-house to Oracle from a managing partner role at then-McCutchen Doyle Brown & Enersen, he said it felt as if “metronome is beating twice as fast.” Companies, especially tech companies move fast—and they need lawyers who can provide answers at the same speed.

Lawyers who can't do that could find themselves cut out of the decision-making process, leading to compliance complications down the road.

“You're either at the table and able to provide an answer when the question comes up, or when the moment comes up when the advice is needed, or you're not there,” Cooperman said. “And if you're not there with an answer, your turn has passed. And they move on, without you and without the legal advice that you might have provided.”

Sometimes, general counsel have done everything right: checked for solutions, entered the meeting prepared with an on-time answer. But, the problem is, that answer is 'no.' The lawyers said most, if not all, general counsel will have to draw a hard no in their career, when a proposal or situation cannot feasibly be done within legal bounds.

Professor Douglas Melamed, of Stanford Law School, speaking during a panel discussion at the Federalist Society's 2018 National Lawyers Convention, held at The Mayflower Hotel in Washington, D.C., on Thursday, November 15, 2018.

Professor Douglas Melamed, of Stanford Law School, speaking during a panel discussion at the Federalist Society's 2018 National Lawyers Convention, held at The Mayflower Hotel in Washington, D.C., on Thursday, November 15, 2018.Cooperman said that, when this happens, he would offer his legal advice and allow other executives to draw their own conclusion that the plan wouldn't work. Others said choosing battles wisely allowed them to say no when it counted most; other executives knew they wouldn't shut down a proposal if another option existed.

When general counsel have credibility with other executives and a strong reason to say 'no,' the decision can empower the legal department. Former Starbucks general counsel Paula Boggs said there was only one time in her decade with the company she needed to take a hard stand. A senior executive had exposed the company to tremendous liability. He was also someone with strong relationships and business ties—making her role, as the GC who had to take action, more difficult. She stood her ground, took action, and “it enhanced even more the reputation of law and corporate affairs.”

Being too inflexible can hurt a GC's reputation as a business partner. But not saying no when it's needed can hurt a GC's reputation as a lawyer. It's a hard line to walk, and one that requires lawyers pick their battles. No one said being a GC was easy.

“If you wanted to be someone's best friend, you shouldn't have gone to law school and certainly not become a leader within the business setting,” Mayes said. “You have to be able to call it … like you see it.”

Caroline Spiezio covers the intersection of tech and law for Corporate Counsel. She's based in San Francisco. Find her on Twitter @CarolineSpiezio.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Google Fails to Secure Long-Term Stay of Order Requiring It to Open App Store to Rivals

'Am I Spending Time in the Right Place?' SPX Technologies CLO Cherée Johnson on Living and Leading With Intent

9 minute read

'It Was the Next Graduation': How an In-House Lawyer Became a Serial Entrepreneur

9 minute read

Renee Meisel, GC of UnitedLex, on Understanding and Growing the Business

6 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250