After Google Memo Suit, How Should Companies Handle Digital Discussions on Diversity?

As more tech workers turn to internal chat apps and message boards to talk about social issues, companies face new legal risks and evidence challenges in litigation.

January 18, 2018 at 05:05 PM

6 minute read

SAN FRANCISCO — Software companies have led the way in using internal messaging apps like Slack and Google Hangouts to do business. But as workers increasingly turn to those platforms to vent about Silicon Valley's diversity woes, the same tools are presenting new legal risks to employers.

Ex-Google engineer James Damore's lawsuit against the search giant contains dozens of pages pulled from internal employee Google+ threads focused on diversity issues, all of which Damore's lawyer uses to argue that the company has created a workplace hostile to conservative, white men.

But even those who vehemently disagree with Damore's lawsuit—and his widely circulated memo about women in the tech industry—said that companies overall need to do a better job of moderating internal forums on diversity, and making clear to employees what the ground rules are.

Employment law attorneys also said companies need to be aware of the risk for things to turn ugly, how they might be held liable if that happens, and the fact that all of these chats might later turn into evidence.

“The challenge that these message boards can present is that [diversity] is a sensitive topic and I think sometimes employees, and people in general, using these online discussion forums may say things that they may not say face-to-face,” said Erin Connell, an employment law and litigation partner at Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe in San Francisco.

“You don't know who is reading it necessarily, or how it will be interpreted,” she added. “And it's in writing, so by definition, there is a written record of it.”

Last week Gizmodo, the popular Silicon Valley tech news website, reported about a separate memo claiming that a senior Google executive in 2015 had asked employees to “stop engaging” on a pro-diversity internal thread he thought was becoming too heated. The report offered a counterpoint to Damore's allegations that Google tolerates aggressive comments only when they fall on the liberal end of the political spectrum. But it also highlighted the challenge companies face in steering the discussion.

Google representatives did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Making Policies Known

Connell said she would not advise companies to prohibit the use of internal online forums to discuss workplace diversity, noting there are protections for concerted activity. But she said that employers need to make their workers aware that policies against harassment and discrimination apply in those channels the same way they would in an actual office.

Mark Konkel, an employment law partner at Kelley Drye & Warren in New York, agreed. Employers should be making sure that workers are confronted with those policies—and asked to agree to them—before logging on to internal forums, he said.

“The real key to reducing liability is not maintaining a static policy on a shelf somewhere, but actively engaging employees,” Konkel said.

He noted that while email and internal chats or message boards have similar traits—they're all fast, informal and electronic—chat tools have particular qualities that seem to lead employees to be more unfiltered.

“In other words, you have people thinking less and writing more than they otherwise would,” Konkel said. “I expect in the future to be trafficking in cases in which a lot of the damning evidence, if there is any, comes in that electronic form.”

From a legal perspective, employers could face claims for violating state or federal anti-discrimination laws if an employee offended by discriminatory comments on an internal channel can show the company knew or should have known about them, but failed to take action. Companies could also be directly liable if managers are the ones accused of making those comments.

'Vat of Evidence'

The lawsuit brought by Damore includes both kinds of allegations. Damore was fired after his memo—in which he argues that tech's gender gap is attributable to biological differences between men and women, not gender bias—was picked up by the tech press and went viral.

The class action suit argues Damore's punishment was reflective of a culture that permits harassment and discrimination against white men and political conservatives. Much, if not all, of the allegations are tied to statements made by employees and managers on internal Google+ message threads.

“What Google has done is create a huge vat of evidence of its selective discrimination against certain categories of people at the expense of others,” said Harmeet Dhillon of the Dhillon Law Group, who is representing Damore and co-plaintiff David Gudeman.

Dhillon said she obtained the threads from clients who did not want to be named. She rebutted any notion that the internal communications were private. “There's no privacy on your workplace server for 80,000 people,” she said.

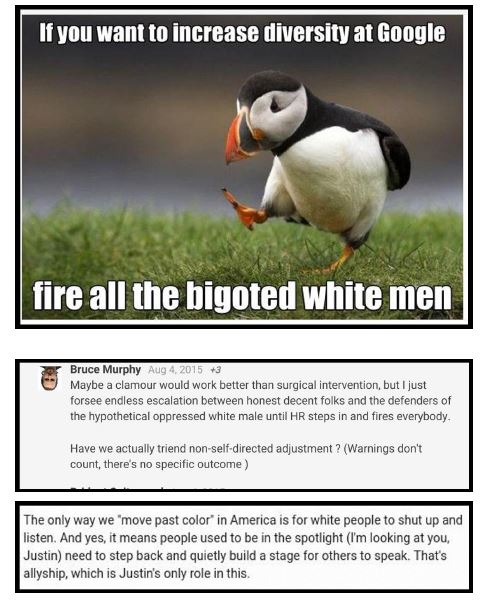

A page from Damore's legal complaint, from a section titled “Anti-Caucasian postings”

A page from Damore's legal complaint, from a section titled “Anti-Caucasian postings”Critics of Damore said Google was within its rights to fire him for expressing views disparaging of women. The company is almost certain to argue in court that he was terminated not because of his political convictions, but for violating workplace policies (which are generally permitted to be more stringent than federal or state anti-discrimination laws).

Dhillon argues those policies are selectively enforced at Google and made up on the spot. Damore, she said, was told he was being fired for “perpetuating gender stereotypes”—a policy she contends was not written down anywhere. “Where's the notice to people? That's completely arbitrary.”

Valerie Aurora, a former programmer in Silicon Valley who now consults tech companies on diversity and inclusion, said that companies do not have to—and should not—create channels where employees are permitted to express views that are sexist, racist or otherwise discriminatory. She also stressed that companies need to take a proactive role in establishing codes of conduct, making them visible in the channel, and enforcing them. “You actually have to moderate,” Aurora said.

The medium, she added, is not the problem. “I have bad news for you: they'll say it in person,” she said. “I don't think the online-ness versus the offline-ness really matters.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Dissenter Blasts 4th Circuit Majority Decision Upholding Meta's Section 230 Defense

5 minute read

DeepSeek Isn’t Yet Impacting Legal Tech Development. But That Could Soon Change.

6 minute read

Law Firms Look to Gen Z for AI Skills, as 'Data Becomes the Oil of Legal'

Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Parties’ Reservation of Rights Defeats Attempt to Enforce Settlement in Principle

- 2ACC CLO Survey Waves Warning Flags for Boards

- 3States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 4Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 5Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250