Shut Out: SCOTUS Law Clerks Still Mostly White and Male

According to a National Law Journal study, the U.S. Supreme Court's clerk ranks are less diverse than law school graduates or law firm associates—and the justices aren't doing much to change that.

December 22, 2017 at 08:13 AM

15 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

A year as a U.S. Supreme Court law clerk is a priceless ticket to the upper echelons of the legal profession. Former clerks have their pick of top-tier job offers and can command $350,000 hiring bonuses at law firms.

Four current justices were formerly clerks at the court—a record number—and three U.S. senators are former clerks. The general counsels of both Apple and Facebook once clerked at the high court. For aspiring appellate litigators and academics, a Supreme Court clerkship opens the creakiest doors.

But amid the luster of being a law clerk, there's an uncomfortable reality: It is an elite club still dominated by white men. While some variables are outside the court's control, few justices seem to be going out of their way to boost diversity.

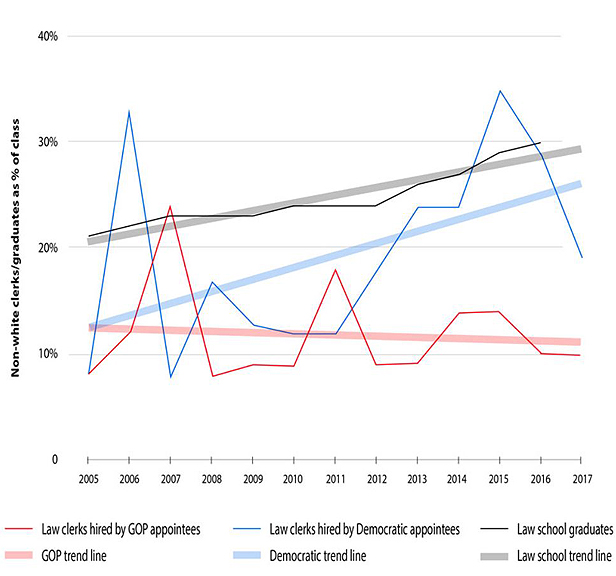

Research conducted by The National Law Journal found that since 2005—when the Roberts court began—85 percent of all law clerks have been white. Only 20 of the 487 clerks hired by justices were African-American, and nine were Hispanic. Twice as many men as women gain entry, even though as of last year, more than half of all law students are female.

The numbers show near-glacial progress since 1998, when USA Today and this reporter undertook the first-ever demographic study of Supreme Court clerks, revealing that fewer than 1.8 percent of the clerks hired by the then-members of the court were African-American (now it is 4 percent,) and 1 percent were Hispanic (now the figure hovers at roughly 1.5 percent). The percentage of clerks who are of Asian descent has doubled from 4.5 percent then to nearly 9 percent since 2005. Then, women comprised one-fourth of the clerks; now they make up roughly a third.

Of the 36 clerks hired by sitting justices this term, one is African-American, two are Hispanic, and three are Asian-Americans, based on the NLJ research.

The ranks of Supreme Court clerks are less diverse and more male than law firm associates, while the stakes for society are certainly higher. Clerks play a crucial role in helping justices pick which cases to grant, and in writing opinions. In both of those roles, the lack of diversity among clerks means the court's handling of race and immigration cases, among others, continues to be shaped by players who have little personal experience to inform the discussion.

Former law clerks as well as the so-called “feeder” judges and law professors who fill the pipeline with potential clerks point to numerous factors that contribute to the dearth. Among them: intense competition to hire top law students at the appeals court level and the range of other opportunities that top minority law students have.

And yet, most justices appear to be taking a passive approach to diversity rather than actively seeking minority clerks or pushing their networks to identify more diverse candidates. “I've never had that precise conversation with any justice,” said Harvard Law School professor Richard Lazarus, a comment echoed by several other clerk-recommenders interviewed for this story. And note this about the feeder judges the justices seek clerks from: The top 19 feeder judges—whose former clerks make up more than two-thirds of all Supreme Court clerks—are white males, according to the NLJ's research.

➤➤ SCOTUS Clerks: Who Gets the Golden Ticket? Join reporter Tony Mauro and Hogan Lovells partner Neal Katyal on Thursday, Dec. 14 for a conference call about clerk hiring and diversity. Click here for more details.

At a 2010 budget hearing, Justice Clarence Thomas seemed to confirm the court's passivity when asked about minority hiring. “I don't think it's up to us to change other federal judges' hiring practices.” He added, “The reality is that Hispanic and blacks do not show up in any great numbers” in the ranks of candidates recommended by the feeder judges.

Georgetown University Law Center professor Sheryll Cashin, a former Thurgood Marshall clerk, said the justices need to be more proactive. “If diversity were a priority,” said Cashin, who's African-American and expert on civil rights issues, “it would not be hard to find qualified people of color even in the elite universe that some of the justices are used to.”

In fact, two of the justices—Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer—have hired roughly equal numbers of men and women—suggesting a proactive approach pays off.

As with the 1998 survey, the NLJ research on clerks was accomplished through scrutiny of available public information, as well as phone calls and emails directed at former clerks and others—not all of whom responded. Unlike other tribunals, including lower federal courts, the Supreme Court does not maintain or release any demographic data about clerks, according to spokeswoman Kathy Arberg.

The National Law Journal asked all nine justices to help verify our data, and all nine declined, Arberg said. All nine justices also declined to be interviewed about the diversity issue generally.

Among the NLJ's key findings:

• Since Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. joined the court in 2005, just 8 percent of the law clerks he's hired have been racial or ethnic minorities.

• At the other end of the spectrum, more than 30 percent of Justice Sonia Sotomayor's clerks have been non-white, making her chambers the most diverse among those justices who have been on the court for more than a year. (Justice Neil Gorsuch has hired seven clerks so far over two terms, three of whom are non-white, for a total of 43 percent.)

• Low numbers span the court's ideological spectrum. Only 12 percent of the clerks hired by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Justice Clarence Thomas since 2005 were minorities. Ginsburg has hired only one African-American clerk since she joined the high court in 1993, and the same goes for Justice Samuel Alito Jr., who became a justice in 2006.

• While Ginsburg and Breyer have hired men and women in equal numbers, other chambers continue to be male-dominated. The court's swing vote, Anthony Kennedy, has hired six times as many men as women law clerks since 2005. Gorsuch, in his second term, has hired just one female law clerk.

• Harvard and Yale law schools have tightened their grip on the clerk “market,” providing half of the court's law clerks since 2005, compared to 40 percent in 1998.

WHY IT MATTERS

The lack of diversity among clerks is important not just because it leaves minorities off the fast track to high-paying jobs. It harms law firms as well as they seek to build diverse practices, said Neal Katyal of Hogan Lovells: “The Hispanic and African-American numbers in particular are things that have long-term consequences for appellate practices.”

Crystal Nix-Hines, a partner at Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan and a former clerk to Marshall and Justice Sandra Day O'Connor said, “The credential stays with you throughout your life.” Nix-Hines said she has had “an eclectic career” that has taken her to journalism, Hollywood and an ambassadorship. Through it all, she said, “I've always been able to kind of re-access the legal profession in part because of my credentials.”

The lack of diversity also has consequences for the court. Though the justices and their law clerks usually downplay clerks' importance, it's undeniable that they wield considerable influence. One study published in the Marquette Law Review found that justices follow the recommendation of clerks 75 percent of the time when granting certiorari.

Justices have said the storytelling of the late Marshall enriched their internal debates, and a more varied cohort of law clerks might do the same. One example: Though the high court routinely takes up cases important to Native American tribes—more than a dozen petitions are currently pending certiorari—the court has never had a clerk known to be Native American.

“This is an institution that is deciding things for everyone,” said Georgetown's Cashin. “Having a range of perspectives and experiences among the law clerks would be useful. There is an elitism and we need to acknowledge it.”

WHY SO FEW MINORITIES?

Theories abound for explaining the low number of minorities clerking at the highest court in the country. One can be summarized as the “Obama trajectory”—top minority law students like Barack Obama (first black editor of the Harvard Law Review in 1990) turning down clerkship opportunities in favor of other career paths. For the future president, heading into politics instead of clerking worked out well.

Judge Edith Jones of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit said attractive options are luring other minorities away too. “Top corporate counsel and top law firms are demanding diversity. The clients want it too,” said Jones, who has sent seven of her clerks to the Supreme Court since 2005. She added, “It may be that not all minority candidates want to become litigators or professors.”

Others point to the dysfunctional system by which federal appeal court judges hire law clerks. An orderly hiring plan that asked judges not to interview first- or second-year law students died in 2014 when more and more judges ignored it. “It's a chaotic process” now, said Judge Margaret McKeown of the Ninth Circuit.

The resulting fierce competition has led some judges to hire clerks based on their first-year grades at law school, which Yale Law School Dean Heather Gerken said “has had a dramatic effect on our pedagogy. It makes the first year more important than it should be. Some students need a longer runway. The late bloomers don't get a fair shot.”

The system also compels some justices to “over-book” clerks who are committed to work for them but then are asked to wait a year or more until there's an opening. For that and other reasons, more and more candidates have multiple clerkships before working at the Supreme Court, where they're paid $79,720.

“To be sure, former clerks are bonus babies,” said Artemus Ward, author of several books about Supreme Court clerks. “But clerking for two years in order to wait for the windfall, particularly after accruing large debts in college and law school, may seem too much to ask.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trump Administration Faces Legal Challenge Over EO Impacting Federal Workers

3 minute read

DOJ, 10 State AGs File Amended Antitrust Complaint Against RealPage and Big Landlords

4 minute read

Judge Slashes $2M in Punitive Damages in Sober-Living Harassment Case

A Look Back at High-Profile Hires in Big Law From Federal Government

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1The Public-Private Dichotomy in State-Created Insurance Entities

- 2How I Made Practice Group Chair: 'It’s a Job About People, First and Foremost,' Says Alexander Lees of Milbank

- 3Morris Nichols Names New Chief Financial Officer

- 4People in the News—Jan. 24, 2025—Klehr Harrison, Willig Williams

- 5Best Practices for Conducting Workplace Investigations: A Legal and HR Perspective

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250