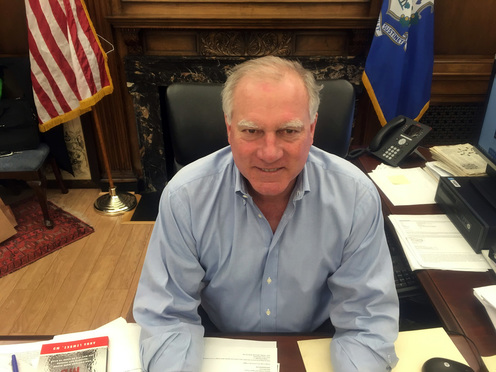

Outgoing AG Jepsen Discusses Accomplishments, Future

Outgoing Connecticut Attorney General George Jepsen recently had a wide-ranging interview with the Connecticut Law Tribune on topics ranging from the environment to opioid abuse and his future.

March 12, 2018 at 03:39 PM

8 minute read

As the state's 24th attorney general prepares to step down in November after seven years on the job, George Jepsen reflected Friday on his accomplishments, his legacy and the many lawsuits and amicus briefs his office has filed during that time.

While Jepsen might be known for his opposition to numerous Trump administration policies—having joined in more than 30 lawsuits and or amicus brief against the administration—the soft-spoken West Hartford resident said he'd like his legacy to be working with attorneys general on both sides of the political aisle. From representing Connecticut and working with attorneys general from both parties on such issues as the recent Equifax breach to fighting Big Pharma in the opioid crisis to investigating Volkswagen for marketing and selling vehicles to circumvent emission standards, Jepsen said his office has plenty to be proud of.

As candidates from both parties wasted no time in lining up to be the state's next attorney general after Jepsen announced in November 2017 he wouldn't seek a third four-year term, the 63-year-old former legislator and Democratic state party chairman sat down for 30 minutes in his Hartford offices with the Connecticut Law Tribune Friday for a look back—and a look ahead.

Connecticut Law Tribune: In your seven years as attorney general, what is the one case your office pursued that you were most proud of and why?

George Jepsen: There are two cases for me. Connecticut uniquely has uncovered systematic price-fixing in the generic drug market and we are far from a conclusion on it. But I'm incredibly proud of the fact that we've built a 47-state bipartisan coalition to root out what is a massive national fraud on the public. We are still very early in that.

In terms of a case that is completed, Connecticut was the lead state in a roughly 20-state coalition, plus the Justice Department, in suing, respectively, Standard & Poor's and Moody's for mislabeling mortgage-backed securities as triple A when, in fact, they were junk, which was the heart of the financial collapse in 2008.

While I can't take credit for finding the legal theory [to prevail in the cases], it was lawyers from this office under my predecessor [Richard Blumenthal] who came up with a novel legal theory to bring these kinds of lawsuits. Standard & Poor's and Moody's had both survived more than two dozen lawsuits. Lawyers from this office came up with a novel theory that pegged it as an unfair trade practice.

We formed this 20-plus state coalition and Standard & Poor's settled first for $1.375 billion and we settled later with Moody's for a little under $870 million. We brought some justice to those who were looted and forced these wrongdoers to pay for what they had done.

CLT: After you announced in November 2017 that you wouldn't seek a third term, you also said you were looking forward to the next chapter in your life. Can you elaborate on what your next career move might be.

GJ: I'm not looking at this time. Over the years I've had not specific jobs offers, but different kinds of entities, have reached out to see if I was interested in being considered for a job from academia to financial services to large law firms.

I believe there will be a market for me and I don't want to have talks with anybody that would put me in a position to be conflicted. So, I am waiting until November.

CLT: Your office has signed on to more than 30 lawsuits and amicus briefs against policies taken by the Trump administration. Why is that and what do you say to those who might argue those suits and briefs are strictly political?

GJ: They are not political. We don't strictly sign on to every opportunity to take a shot at the Trump administration. Some of these letters are signed on, on a bipartisan basis. Republicans have signed on—not a lot—but a number of them have. I've cautioned within the family of Democratic attorneys generals that if we bring frivolous lawsuits, we hand the Trump administration cheap and easy victories.

So, I try to be careful to review any action before we sign on. We already have won some legal actions, like the transgender in the military issue and some of the Clean Air Act suits that we've filed. It's not commonly understood, with respect to resources, that most of the work is handled by separate states.

There are actually only two cases where Connecticut is shouldering the burden of bringing legal action. One is Brunner Island, which long predates the Trump administration. [That case claims the Environmental Protection Agency failed to act on a petition involving emissions from Brunner in Pennsylvania.] It's Connecticut and New York working together. The issue was taken up in 2015 under the Obama EPA, so it's a continuation.

The second case is on the gaming casino and the proposed amendments to the compacts that would allow a slots parlor to be erected in East Windsor. We are doing what we are supposed to do, which is defend the laws of the state of Connecticut. We are representing the [Gov. Dannel] Malloy administration and have joined the tribes in terms of challenging the Bureau of Indian Affairs failure to say—one way or another, up or down—on [acting on amendments within 45 days] of the proposed compact amendments.

CLT: Many of the legal actions your office has signed off on deal with the environment. Are these legal actions, lawsuits and amicus briefs having a direct effect on changing policy in Washington, D.C.? And, if so, how?

GJ: We are often in disagreement with [EPA Administrator] Scott Pruitt and the EPA. There is not a lot in where we agree with him and we can get specifics on where our legal interventions have had a direct impact.

The jury is out as legal actions take months and, some of them, take years. We have yet to see what the impact [of legal filings] will be.

The environmental issues stand out for two reasons: One is state attorneys general are deputized to enforce the protection of the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act. And, second, Connecticut is downwind from just about every spot in the union. Our air quality is directly impacted by activities in other states and so to protect our citizens we need to go to court on issues like Brunner Island to make other states stop polluting.

There is a good-neighbor provision in the Clean Air Act where a downwind state is doing everything it can, like Connecticut, but is being adversely affected by the failure of these other states to take appropriate measures. Under the good-neighbor provision of the act, we can go to the court to get the EPA to do its job, which is to adopt regulations that protect not just their citizens but Connecticut's citizens as well. We have an obligation to protect our residents and we are going to do it.

CLT: The opioid epidemic in the state is on the rise. In October, your office was one of 41 in the country that announced it was issuing subpoenas to several pharmaceutical drug manufacturers for information about how the companies market opioids. What came of those subpoenas and what more can and/or is your office doing to address the crisis?

GJ: I'm proud of the leadership role Connecticut has taken on this extremely important issue. As of June, the opioid multistate [litigation] was focused on a single manufacturer and Connecticut led the charge to expand the multistate to include other manufacturers. Now, the 41 states are collectively going after the six largest manufacturers.

We also successfully drove a decision to investigate the distributors. There are three primary distributors. Those are the folks that buy from the manufacturers and then distribute them to local pharmacies. The three control almost 90 percent of the market.

We've persuaded the distributors and manufacturers that this is an issue in which they know we aren't going away. There are also face-to-face negotiations with the manufacturers and distributors prospectively about what the shape of a global settlement will take.

From our prospective, our priorities are to conduct change; that is to say what are the rules down the road in which you will manufacture and distribute so that we don't get the same horrific morass we are in right now. The second priority is treatment of existing addictions and prevention and education policies that can be undertaken to lessen the likelihood of anybody else getting addicted.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

How I Made Partner: 'Work With as Many People as Possible,' Says Kyle Dorso of Brown Rudnick

A Conversation with NLJ Lifetime Achievement Award Winner Jeh Johnson

Trending Stories

- 1States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 2Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 3Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

- 4Trump's DOJ Delays Releasing Jan. 6 FBI Agents List Under Consent Order

- 5Securities Report Says That 2024 Settlements Passed a Total of $5.2B

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250