Reversal of Bite-Mark Murder Conviction Mandates Hard Look at Forensic Evidence

Courts may not be able to foresee how science will change, but they can—and should—limit forensic experts from overstating the probative value of their opinions.

March 16, 2018 at 01:03 PM

4 minute read

On March 1, a Hartford judge officially dismissed a decades-old murder charge against Alfred Swinton. Swinton, who served 18 years of a 60-year sentence, was released last June after DNA testing exculpated him, and a forensic expert who testified at his trial recanted.

On March 1, a Hartford judge officially dismissed a decades-old murder charge against Alfred Swinton. Swinton, who served 18 years of a 60-year sentence, was released last June after DNA testing exculpated him, and a forensic expert who testified at his trial recanted.

But it was not until this month, when the state's attorney confirmed that her office would not retry Swinton, that the miscarriage of justice that claimed nearly two decades of a man's life was rectified. Swinton's story provides an opportunity for Connecticut to critically examine the ways in which forensic evidence can threaten the integrity of the criminal justice system—and how, in the process, we can look for answers.

At Swinton's 2001 murder trial, the most damning evidence came from Gus Karazulas, the chief forensic dentist for the Connecticut State Police. Karazulas, who claimed to be an expert in analyzing bite marks, testified that bite marks found on the murder victim's body had been made by Swinton. His opinion rejected any possibility of error; Karazulas testified, “I believe that with reasonable medical certainty without any reservation that these marks were created by [Swinton's] teeth.” That sentence was quoted by the Connecticut Supreme Court in upholding Swinton's conviction.

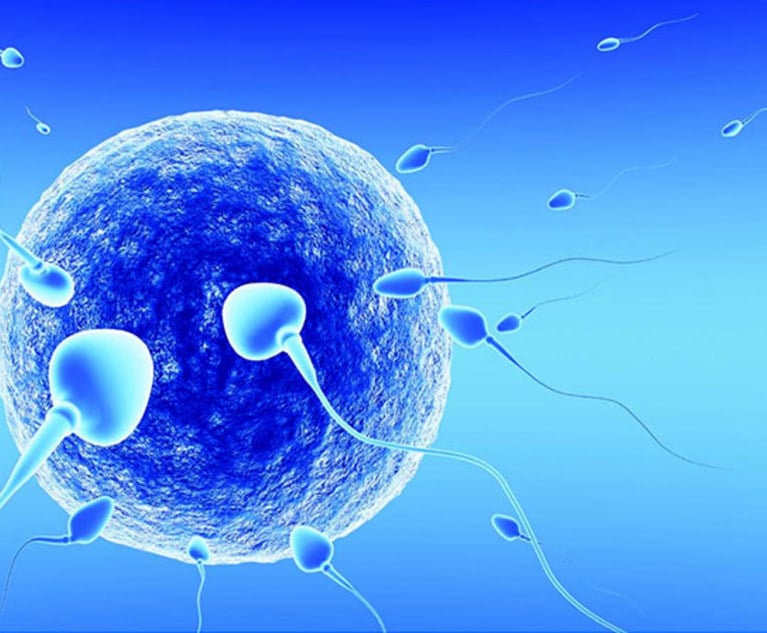

Bite-mark analysis relies on two premises: first, that human dentition, like DNA, is entirely unique; and second, that human skin can record a dental impression with enough sensitivity to be accurately matched to an individual. The problem is that neither premise has been proved. In the years since Swinton's conviction, bite-mark analysis has been almost entirely debunked.

In 2009, the National Academy of Sciences published a congressionally commissioned report on the state of forensic science in the courtroom. The report was critical of a wide range of forensic specialties, but it singled out bite-mark analysis as particularly dubious. It found “no evidence of an existing scientific basis for identifying an individual to the exclusion of all others.” In 2016, a report by the United States President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology affirmed this conclusion and went a step further, declaring that the odds of transforming bite-mark analysis into a scientifically valid method were nil.

Acting on these developments, Swinton's attorneys asked Karazulas to re-evaluate the state of forensic dentistry and his own opinions. To his credit, Karazulas did so wholeheartedly. He filed an affidavit on Swinton's behalf that discredited bite-mark analysis as a valid forensic method and retracted his opinion about Swinton. Approximately 30 other defendants across the country have been exonerated in similar circumstances, but many more remain incarcerated based on bite-mark testimony.

The judicial branch's role as gatekeeper when it comes to scientific evidence is inherently limited. It is only as good as the prevailing view in the scientific community at the time. When our Supreme Court affirmed Swinton's conviction in 2004, for example, it was able to marshal compelling evidence that bite-mark analysis was methodologically valid and employed in courtrooms nationwide. This raises a difficult but important question: how can courts protect the rights of criminal defendants when the reliability of a forensic method may shift radically over time?

One answer may lie in imposing stricter limits in criminal cases on how expert forensic opinions are given. According to the latest research, many forensic methods—even if generally reliable—carry meaningful error rates. And most, with the exception of DNA, are not able to identify a perpetrator to the exclusion of others. Yet across all fields, experts elide these critical limitations, overstating the probative value of their evidence and expressing a confidence level that far exceeds what the relevant science can justify.

Opinions rendered with empirically unfounded certainty are not a matter of expertise or professional judgment, they are scientifically invalid. And the consequences are alarming. A three-year study by the Department of Justice and the FBI of 3,000 criminal cases involving microscopic hair analysis revealed that FBI examiners had provided scientifically invalid testimony in more than 95 percent of cases in which testimony was used to convict a defendant.

Courts may not be able to foresee how science will change, but they can—and should—limit forensic experts from overstating the probative value of their opinions. The 2016 report from the President's Council provides concrete recommendations in this area, urging courts to preclude forensic experts from using a laundry list of common phrases that are scientifically indefensible. One of those phrases is “to a reasonable degree of scientific certainty,” almost precisely the language that helped convict Swinton.

Turning a critical eye to forensic science and seeking avenues for reform will not atone for what was done to Swinton, but it is an essential first step.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trump Administration Faces Legal Challenge Over EO Impacting Federal Workers

3 minute read

Settlement Allows Spouses of U.S. Citizens to Reopen Removal Proceedings

4 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Some Thoughts on What It Takes to Connect With Millennial Jurors

- 2Artificial Wisdom or Automated Folly? Practical Considerations for Arbitration Practitioners to Address the AI Conundrum

- 3The New Global M&A Kings All Have Something in Common

- 4Big Law Aims to Make DEI Less Divisive in Trump's Second Term

- 5Public Notices/Calendars

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250