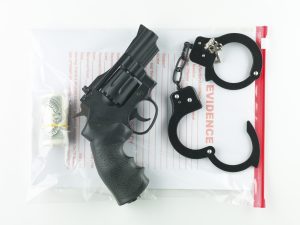

Viewpoint: Connecticut's Gun Seizure Law Can Serve as National Model

Connecticut was the first state in the nation to pass a law to allow police to obtain a court order to seize guns from anyone who presents an imminent risk of harming himself or someone else.

April 27, 2018 at 03:57 PM

5 minute read

Two Connecticut lawmakers who don't often agree are urging the adoption of gun seizure laws throughout the country modeled on Connecticut's 1999 statute, CGS §29-38c, also known as the state's Gun Seizure Law.

State Rep. Arthur O'Neill (R) is contacting legislative leaders in the 46 states that don't have similar legislation. He is urging them to consider adoption of a gun seizure statute, also called a risk warrant, in each of their states, modeled on the Connecticut law.

In the meantime, U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D) announced he will propose federal legislation also modeled after Connecticut's Gun Seizure Law.

Connecticut was the first state in the nation to pass a law to allow police to obtain a court order to seize guns from anyone who presents an imminent risk of harming himself or someone else. This statute was passed in response to the 1998 Connecticut Lottery shooting rampage, in which a disgruntled employee shot and killed the president of the lottery and three employees before killing himself.

Under the provisions of Connecticut's Gun Seizure Law, police, after investigating and determining probable cause, may apply for a warrant to seize an individual's firearms. Following the entry of a seizure order, the court must hold a hearing within 14 days and, after the hearing, may order the retention of the weapon or weapons for as long as one year.

A 2008 report by the Office of Legislative Research (OLR 2008-R-0280) determined that, by 2008, police had applied for 222 warrants and seized 1,713 guns. The report pointed out a great variance in the use of the seizure law among Connecticut towns. Only 54 towns used it, with West Hartford the most frequent user at 23 times. The large cities of Hartford and Bridgeport reported no use of the law.

The OLR report did not present any reasons why the towns and cities would vary in their use of the Gun Seizure Law. Of the 222 applications, only two were denied (one for lack of probable cause and the other because the guns had already been seized).

The information collected for the report indicated further that the most frequent reason for the use of the statute was the threat of suicide (40 percent of cases). This is consistent with the fact that the majority of gun deaths in America are by suicide. The next most common reasons were threat of murder (14 percent), mental illness (12 percent), violence (12 percent), threat of murder/suicide (9 percent), reckless gun use (4 percent) and other (9 percent).

When the seizure law was being considered by the Legislature, its opponents called it the “turn in your neighbor law,” claiming it would be used by disgruntled neighbors to get even. This clearly hasn't been the case. The report pointed out that while the statistics on complainants was not comprehensive, their data suggests 32 percent of the cases were initiated by spouses, 15 percent by relatives other than spouses, 14 percent by law enforcement (including probation and parole officers), and 10 percent by health care professionals.

The report indicated that in 95 percent of the cases where the police had a seizure order, they were actually able to seize weapons. Also, the courts kept seizure orders in place after hearings in 81 percent of the cases. In the majority of cases, police were ordered to hold the weapons for up to a year. In some cases, the guns were ordered transferred to someone else, destroyed or sold.

A more recent report, prepared jointly in 2014 by Duke University, Yale University and the University of Connecticut, indicated the Gun Seizure Law had been used to seize guns from Connecticut residents in 764 cases since its passage in 1999. In addition, data confirmed that use of the law increased following the December 2012 mass shooting in Newtown.

While it is impossible to tell how many lives have been saved by this law, we can tell from the OLR report that the law has been used effectively to seize guns in dangerous circumstances. In very serious cases, the seizure law has successfully focused on removing guns from the hands of high-risk individuals. Connecticut is safer because of the passage of this statute.

Seizing guns from individuals who lawfully obtained them is a serious action and the Legislature should be vigilant to be certain that such a law is not misused. Initially, the OLR did a good job of reporting on the use of the law. It issued reports in 2002, 2006 and 2008. But it has been 10 years since the last report was issued. We continue to need to know about the use and effectiveness of the Gun Seizure Law.

In 2014 this editorial board expressed its support for the Gun Seizure Law and suggested the Legislature take a closer look at its uneven use by some towns, and an explanation as to why it is not used at all in other towns. Also, we noted the importance of having the Legislature require the OLR to issue future reports on a regular, periodic basis. Now that 46 other states and the federal government may be considering adoption of laws modeled on Connecticut's, it is time we review what is working and what could be improved.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

The Stormy Daniels 'Hush Money' Trial: Donald Trump Should Be Very Worried

7 minute read

Shining a Light on Opposing Hate: The Palestinian Protesters Who Defended New Haven's Menorah

6 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250