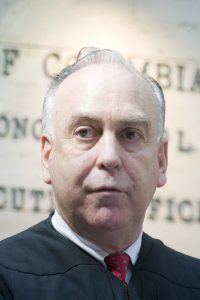

Viewpoint: Judge Ellis Is a Bully in a Black Robe

He has described himself as “Caesar in my own Rome,” and his bizarre behavior, thus far directed almost exclusively at the federal prosecutors, suggests he truly believes that self-description.

August 16, 2018 at 12:05 PM

5 minute read

T.S. Ellis, III, senior U.S. district judge for the Eastern District of Virginia. Photo by Diego M. Radzinschi/THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL.

T.S. Ellis, III, senior U.S. district judge for the Eastern District of Virginia. Photo by Diego M. Radzinschi/THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL.

The ongoing trial of Paul Manafort in federal court in Virginia for bank fraud and tax evasion is providing a stark example of a federal judge abusing his courtroom authority to the extent he may be jeopardizing the prosecution's ability to get a conviction, which the evidence suggests it should win. U.S. District Judge T.S. Ellis has been described in press coverage of the trial as presiding as an “activist judge”; in this case that is a euphemism for a bully in a black robe.

He has described himself as “Caesar in my own Rome,” and his bizarre behavior, thus far directed almost exclusively at the federal prosecutors, suggests he truly believes that self-description.

A comment the judge made during pretrial proceedings in the case probably foreshadowed what we are now witnessing. He expressed his belief then that the government was not really interested in Manafort; it was just using that indictment to pressure him to provide evidence against President Donald Trump. It has been downhill since then for the prosecution.

Ellis is unbridled in his willingness to disrupt the prosecution's questioning and make disparaging comments about the government evidence. He interrupted testimony about Manafort's lavish lifestyle to say “It is not a crime to be rich.” When the prosecutor was examining Rick Gates, Manafort's former partner and now the government's key witness, he again interrupted certain questioning of Gates, stating that it “didn't amount to a hill of beans.” When Gates testified that Manafort was well aware of the financial transgressions Gates was engaging in because they had been directed by Manafort and he “was watching everything closely,” Ellis interrupted: “Not that closely, because you were able to steal all that money from him.” After many more such prejudicial interruptions and denigrating characterizations, the frustrated prosecutor complained, but the judge dismissed his grievance with the comment that he would stand on the record. The prosecutor shot back that he would do the same, but the judge had the last word: “Then you would lose.”

But this judge does not limit his assaults to the government's evidence; he attacks and humiliates the prosecutors themselves. He has demanded that they “reign in your facial expressions,” not “furrow your brows” and “stop rolling your eyes as if to say 'why do we have to put up with this idiot judge.'” At one point the prosecutor had to question how he could be scolded for both not looking at the judge and rolling his eyes at the same time. In another particularly tense exchange, he scornfully accused the prosecutor of having tears in his eyes, and when the prosecutor objected and denied that was the case, the judge retorted: “Well, they are watery.”

His incessant scolding and criticism of the prosecution team assumes an even sharper point when contrasted with his obsequious behavior toward the jury. His clumsy charm offensive consisting of lame jokes and even lamer self-depreciating stories to the jury somehow makes his surliness and testiness directed at the prosecutors even more offensive.

Much, indeed most, of his abusive behavior takes place in the presence of the jury, and that is what is so disturbing. In any trial, the jury quickly realizes that the judge is the only player in the process without a stake in the outcome; the only neutral. Naturally, then, as they undertake their search for the truth, they afford great weight to the judge's comments. That is why good judges are scrupulous to avoid even the appearance of favoring one side or the other. After 31 years on the bench, it is inconceivable that Ellis does not know that, so one must conclude he simply does not care. That was evident in his telling remark during the trial: “Judges should be patient. They made a mistake when they confirmed me. I'm not very patient, so don't try my patience.” Mistake indeed.

This judge is not just devoid of sound judicial temperament; his unwillingness to control himself—apparently because Caesar has no such obligation—borders on the shameful, and it came to a climax at the end of the second week of trial. At the close of testimony that day, Ellis realized the government's expert witness had been sitting in the gallery during the testimony of Rick Gates, and he exploded at the prosecutors. He accused them of violating his clear order on sequestration of witnesses and warned them never to try that again.

The next day, the government filed a motion to correct the record, pointing out that prior discussions of that topic with the court had resulted in Ellis actually issuing exactly the opposite order. Because the jury had witnessed his tirade the previous day, he had to issue a curative instruction, but Cesar could not bring himself to apologize. The best he could do? “Put aside any criticism; I was probably wrong in that. This robe doesn't make me anything other than human.”

If only the Honorable T.S. Ellis really believed that.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

The Stormy Daniels 'Hush Money' Trial: Donald Trump Should Be Very Worried

7 minute read

Shining a Light on Opposing Hate: The Palestinian Protesters Who Defended New Haven's Menorah

6 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Is It Time for Large UK Law Firms to Begin Taking Private Equity Investment?

- 2Federal Judge Pauses Trump Funding Freeze as Democratic AGs Launch Defensive Measure

- 3Class Action Litigator Tapped to Lead Shook, Hardy & Bacon's Houston Office

- 4Arizona Supreme Court Presses Pause on KPMG's Bid to Deliver Legal Services

- 5Bill Would Consolidate Antitrust Enforcement Under DOJ

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250