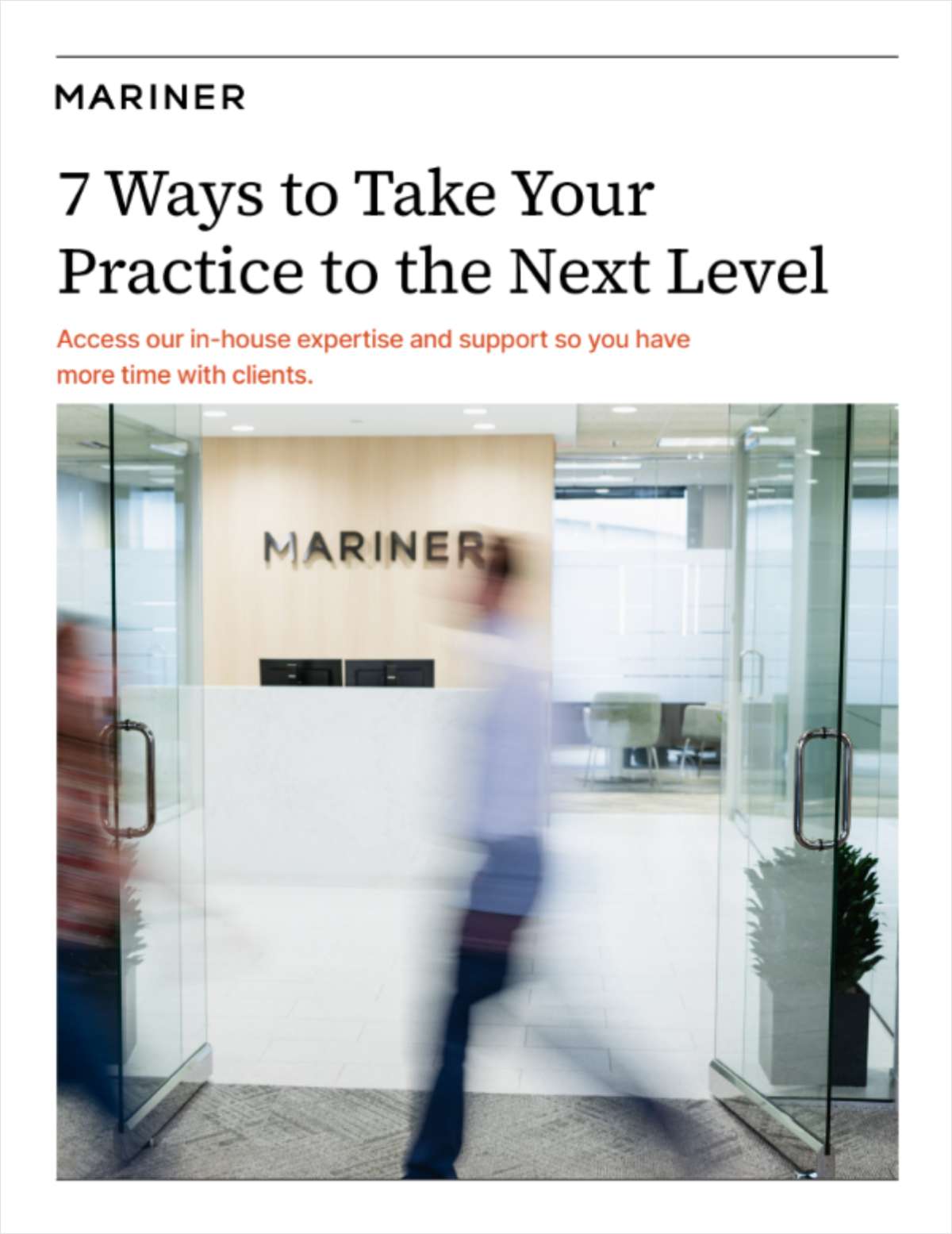

Connecticut Gov. John G. Rowland, right, swears in Judge Francis M. McDonald as chief justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court in 1999. Photo: Bob Child/AP

Connecticut Gov. John G. Rowland, right, swears in Judge Francis M. McDonald as chief justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court in 1999. Photo: Bob Child/APA Conservative Chief Justice With a Libertarian Streak: Francis McDonald Remembered

Francis McDonald was a justice and chief justice on the Connecticut Supreme Court for a short period of time, but he had a strong impact on the institution, many believe.

October 12, 2018 at 06:02 PM

5 minute read

Known in the state's legal circles as an outspoken, witty and compassionate jurist who tilted right but had a libertarian streak, former Connecticut Chief Justice Francis McDonald died Oct. 8 in Waterbury. He was 87 years old and passed away due to complications from pneumonia.

A former FBI agent, prosecutor and Superior Court judge, McDonald joined the state's high court as associate justice in 1996. He became chief justice in September 1999 and stayed in that post until January 2001, when he reached the mandatory retirement age for judges of 70.

Although he was on the Supreme Court for less than five years, including 16 months as chief justice, the Waterbury native and Yale graduate was never a sure vote for either side of the political aisle, many said. Although he was considered a conservative, he often sided with Justice Robert Berdon, then the court”s most liberal justice.

“I considered him a more libertarian type, but it was often the case where McDonald and Berdon were the court's two dissenters,” said Wesley Horton, a partner with Hartford's Horton, Dowd, Bartschi & Levesque. Horton, who has appeared before the state's high court about 130 times, including about 20 in front of McDonald, said of McDonald and Berdon: “There you had the right wing of the court meet the left wing of the court and be opposed to where the center of the court was.”

One example of McDonald's libertarian streak was his dissent in the 2000 ruling of Seymour v. State Elections Enforcement Commission, said William Dunlap, a professor of law at Quinnipiac University School of Law.

“He had a reputation as a frequent dissenter and a libertarian. Seymour was one dissent, particularly, where those two merged,” said Dunlap, who also teaches constitutional and criminal law. McDonald, along with Justice William Sullivan, who would succeed McDonald as chief justice, were in the 3-2 dissent, which McDonald wrote.

The Seymour case involved a candidate for local office who did not have big campaign coffers, who wrote a press release on her computer and faxed it to a local newspaper. Election laws at the time required that any time any money was spent on that type of publicity, the publicity had to have the phrase “paid for by” and the name of whomever financed it. The commission held that the candidate violated the law and that was upheld by the state Supreme Court.

“He issued a passionate First Amendment defense arguing that the law simply should not apply to people who engage in this kind of campaigning from their homes. He wanted to prevent the government and established political parties from making it more difficult for individuals to break into the political system,” Dunlap said Friday.

Horton, who authored “The History of the Connecticut Supreme Court,” said McDonald “was interesting as a justice in oral arguments. His questions were unpredictable. You could prepare and prepare and prepare, but he'd come up with a question you just had not thought of and that happened time and time again.”

The unpredictability was echoed by Patrick Tomasiewicz, a partner with Hartford's Fazzano & Tomasiewicz, who knew McDonald off the bench.

“He was a fun, smart, witty and an unpredictable judge,” said Tomasiewicz, who is also an adjunct paralegal studies professor at the University of Hartford. “I agree he was somewhat a libertarian. He was also a man who had great respect for his position as judge and who wore the robe with honor and dignity.”

Tomasiewicz recalled one time that McDonald, then a Superior Court judge, almost found him in contempt.

“The case was about prejudgment remedy in a real estate matter and he ruled in my favor,” Tomasiewicz said Friday. “During the hearing, I was advocating for a position quite forcefully, and I think I got a little bit out of line,” he said. Tomasiewicz was told to approach the bench, where McDonald asked, “Do you want to go to the can?”

“I said absolutely not. He then told me to tone it down, and I did just that,” Tomasiewicz said.

While McDonald was known as an outspoken, strong and sometimes complicated jurist, those who knew him said you definitely knew he was a New Englander. ”He went to Yale and was a Yankee through and through,” Tomasiewicz added. “He also had a wonderful and wry sense of humor.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Connecticut Movers: New Hires at SkiberLaw, Verrill and Silver Golub & Teitell

3 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Arnold & Porter Matches Market Year-End Bonus, Requires Billable Threshold for Special Bonuses

- 2Advising 'Capital-Intensive Spaces' Fuels Corporate Practice Growth For Haynes and Boone

- 3Big Law’s Year—as Told in Commentaries

- 4Pa. Hospital Agrees to $16M Settlement Following High Schooler's Improper Discharge

- 5Connecticut Movers: Year-End Promotions, Hires and an Office Opening

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250