Fake News: RGB Papers 100-Year Restriction 'Not True,' Supreme Court Says

The restrictions that justices put on their Supreme Court papers after they are no longer on the bench have generated considerable controversy over the years.

April 11, 2019 at 06:06 PM

5 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

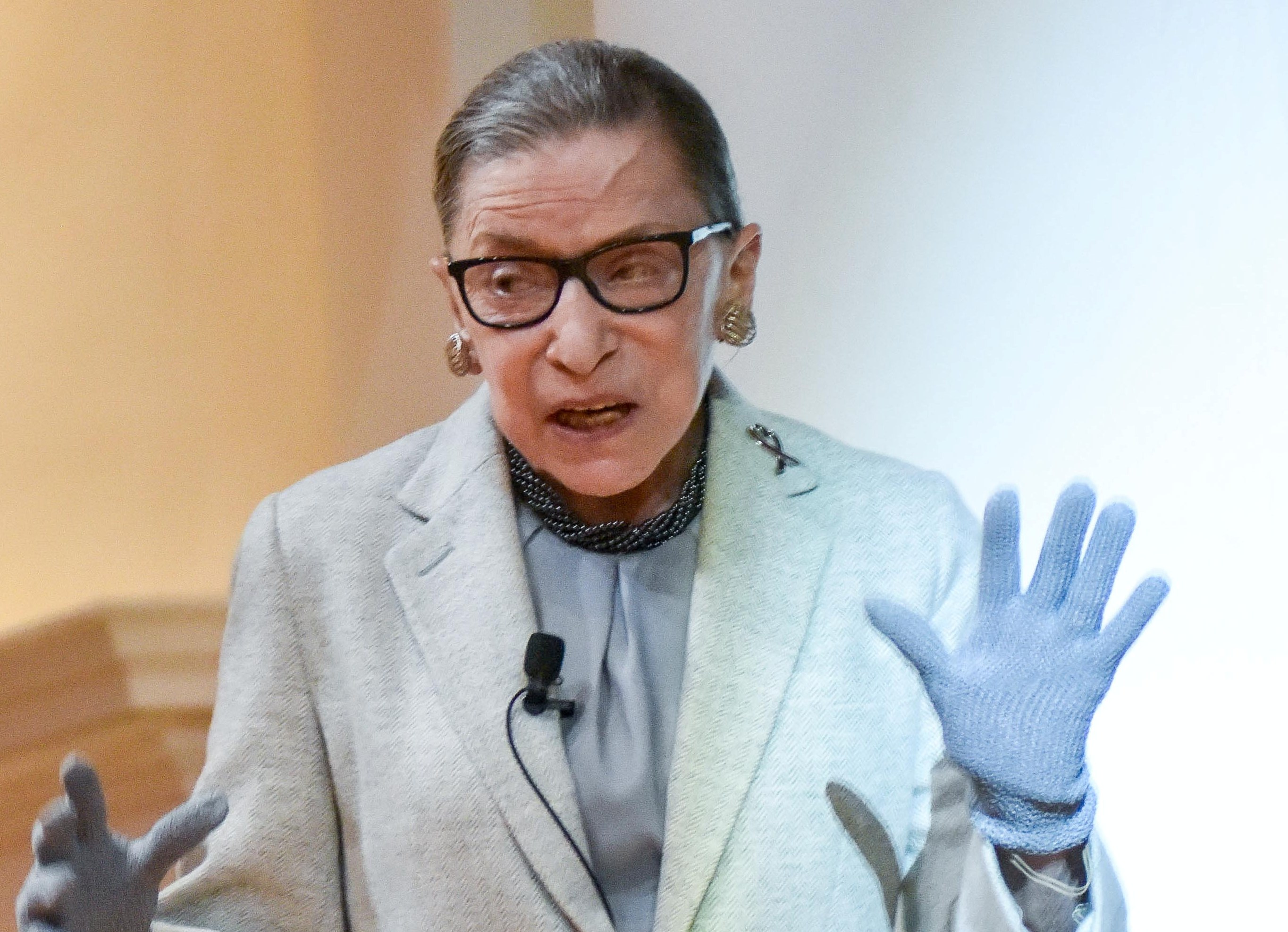

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

A book author's claim that Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg has imposed a 100-year restriction on access to her U.S. Supreme Court papers after she leaves the bench triggered a swirl of criticism and concern this week among historians, journalists and law professors.

But it turns out the 100-year restriction as stated in the new book “Ruth Bader Ginsburg: A Life,” wasn't accurate.

“The arrangements mentioned in the book are not true,” Kathy Arberg, head of public information at the Supreme Court, told The National Law Journal. “The justice has not announced her plans for her Supreme Court papers and would never impose such a restriction.”

The restrictions that justices put on their high court papers after they are no longer on the bench have generated considerable controversy over the years, particularly when access to the papers is barred until many years after every justice with whom the departed justice has served is no longer living.

The recent controversy followed a tweet posted by Lynda Dodd, a professor of legal studies and political science at the City University of New York. Dodd highlighted part of the bibliography of Jane Sherron De Hart's new book about Ginsburg.

The bibliography excerpt said: “Papers from her tenure as associate justice of the Supreme Court (1993—) will not be available to researchers until a hundred years after the last justice with whom she has served is no longer alive.”

The 100-year restriction seemed out of character for a justice who has been one of the most transparent and accessible justices in modern times.

De Hart told The National Law Journal in an email: “My information is based on the guide to the RBG papers in the manuscripts division of the Library of Congress. It is not a matter that I have ever discussed with the justice.”

Janice Ruth, acting chief of the manuscript division of the Library of Congress, which houses Ginsburg's pre-judicial and court of appeals files, said Ginsburg “has been very receptive to requests by researchers.”

The Library of Congress does not have any of Ginsburg's Supreme Court papers, Ruth said. The draft guide to Ginsburg's papers, Ruth said, does not contain a 100-year restriction. Files that include specific cases from Ginsburg's years on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit are restricted so long as any judge who participated in that case is alive, Ruth said.

Unlike rules governing the preservation of presidential papers, no law controls the fate of justices' papers, a fact that has resulted in a wide range of arrangements made by justices and their heirs. Justices typically do not disclose their preservation plans before their death, so the future homes of papers of current justices are unknown.

“Justices own their own papers, and unfortunately, they are under no legal obligation to preserve them,” said Kathryn Watts, a University of Washington School of Law professor who has written about justices' papers.

Justice Hugo Black burned some of his papers. Justice David Souter, who retired in 2009, has specified that his papers, donated to the New Hampshire Historical Society, would not be made public until 50 years after his death.

At the other end of the spectrum, Justice Thurgood Marshall caused a posthumous controversy by deciding that his papers would be released as soon as he died. There was no way of predicting when that would happen, but he died in 1993, less than two years after he retired, so some of the files revealed very recent material to the public.

Chief Justice William Rehnquist angrily wrote to the Library of Congress, “I speak for a majority of the active Justices of the Court when I say that we are both surprised and disappointed by the library's decision to give unrestricted public access to Justice Thurgood Marshall's papers.”

Justice Antonin Scalia (2010). Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL

Justice Antonin Scalia (2010). Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNALThe late justice Antonin Scalia's family struck a middle approach with his papers, which will be housed at the Harvard Law School Library. Papers from his tenure as a judge on the U.S Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit from 1982 to 1986 and as a Supreme Court justice from 1986 to 2016 will begin to be released in 2020, or roughly four years after his death.

But files about specific cases “will not be opened during the lifetime of other justices or judges who participated in the case,” Harvard said.

Since some of his recent colleagues were relatively young, that means Scalia's files on blockbuster cases such as same-sex marriage and the Affordable Care Act won't likely be made public for decades.

Read more:

How Merrick Garland Landed a Supreme Court Clerkship With Brennan

Scalia's Papers, Including Emails, Donated to Harvard Law School

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trump Fires EEOC Commissioners, Kneecapping Democrat-Controlled Civil Rights Agency

Trump Administration Faces Legal Challenge Over EO Impacting Federal Workers

3 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250