Changes Coming For Access to Justice?

I listened to an interesting podcast on Slate’s “Amicus” site the other day. The title was “Lawyers, Who Needs Them?” Dahlia Lithwick was…

August 21, 2019 at 12:16 AM

5 minute read

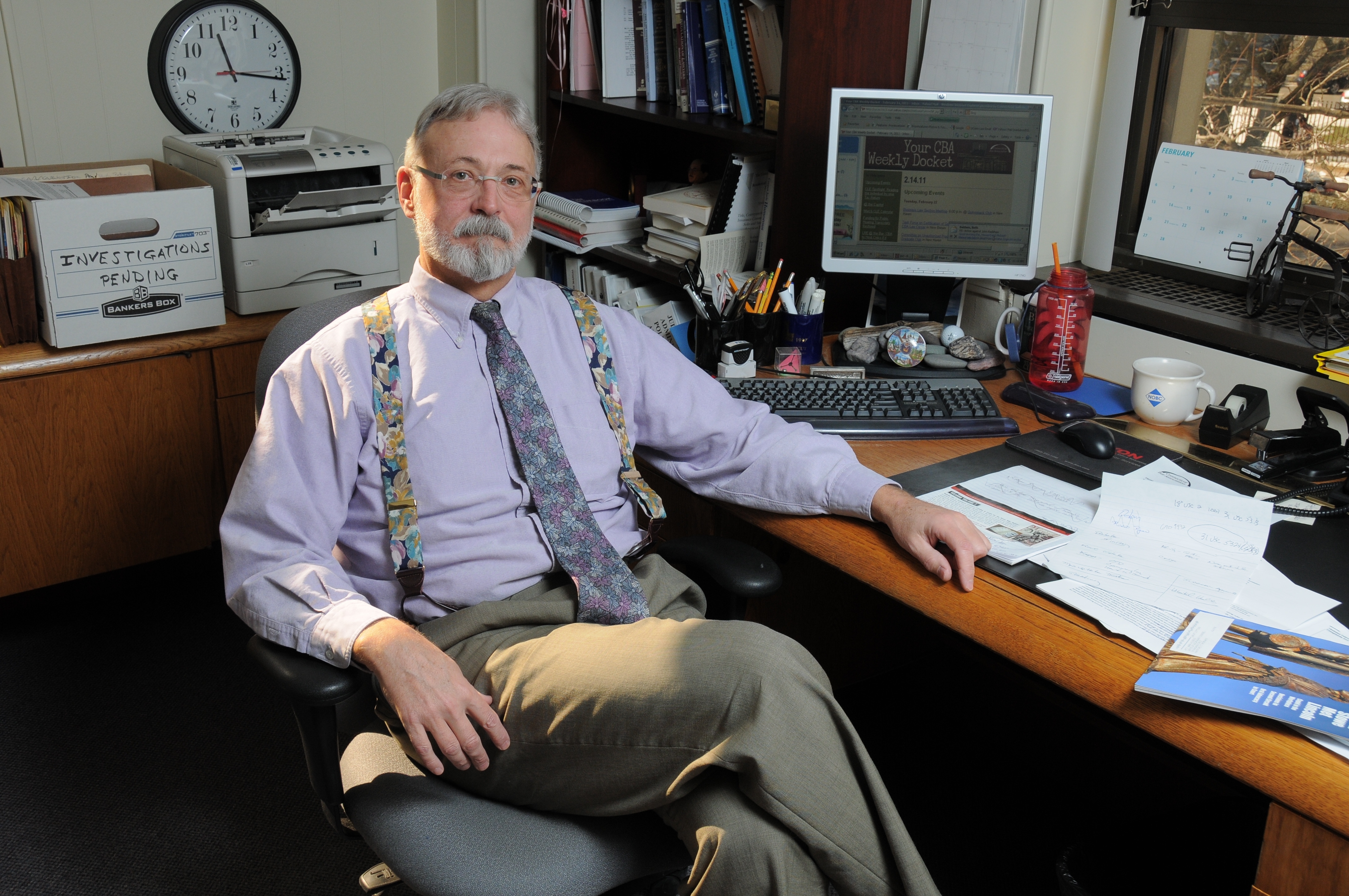

Mark Dubois

Mark Dubois

I listened to an interesting podcast on Slate’s “Amicus” site the other day. The title was “Lawyers, Who Needs Them?” Dahlia Lithwick was interviewing Rebecca Sandefur, whose Wiki bio describes her as “an American sociologist who won a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship in 2018 for ‘promoting a new, evidence-based approach to increasing access to civil justice for low-income communities.’

If the last sentence doesn’t cause you to pause or mutter “WTF?,” read it again. Yes, this professor got money to study whether the world might be better off if there were places other than law offices where folks could get quick and easy access to legal information. I have to admit she might have a point though.

As we all know, much of what we do every day is explain the law to folks lost in the legal or regulatory forest. Smart folks call it knowledge asymmetry. Studies, including one by the American Bar Foundation which I wrote about some time ago, tell us that many people don’t perceive legal problems or issues the way we do. (I’m talking about non-criminal stuff here. Anyone who has been arrested understands they have a legal problem. If they don’t, their free lawyer will explain it.)

Sandefur repeated a statistic I’ve seen elsewhere, that 85 percent of most cases these days involve one party without a lawyer. When these folks find themselves in the soup because of a debt, eviction, divorce, lawsuit or some injury or insult, real or perceived, many just shrug, assuming their problem is either the result of bad luck or God’s will. They figure that either they understand enough to get by on their own or that whatever the result is, they don’t have too much hope of being able to change it, so they just go with the flow.

Sandefur doesn’t quibble with the idea that many would have a better result with a lawyer by their side; there are studies that prove this pretty conclusively. But defining the problem as something that requires them to hire legal talent seems to be the problem. Getting them to pay a lawyer to tell them they need to hire her is a real stretch.

Sandefur recommends de-coupling legal information from legal representation. Apparently this is happening already in England, and the “legal information for profit” sector is booming. On this side of the Atlantic, such ideas run up against the bar and our definition of the practice of law. Because I used to be Connecticut’s chief unauthorized practice of law enforcer and have handled literally hundreds of these cases, it’s a subject I know pretty well. The rub is in the difference between information, which everyone has a First Amendment to give or sell and “specific, individualized legal advice” which is our exclusive province. The penalty for crossing the line is a felony.

Funny thing, that felony law. I worked with the bar for more than 10 years to get unauthorized practice raised to a felony. A guy I was after a decade ago just got arrested for felony unauthorized practice. But by the time we got the law changed, folks in the “access to justice” sector were beginning to discuss the same things as Sandefur. Now many are not so sure that we have the fence is in the right place.

I sat for an interview a few weeks ago with a law student studying in an Access to Justice class at UConn Law who wanted to understand all of this from a regulator’s viewpoint. (I guess I am a primary source now. Age has some privileges.) I explained that I didn’t think the bar would be too upset with an industry that helped people understand why they needed to hire a lawyer, but that my experience had been that the real problem was with making sure that the information was correct. My rhetorical question has always been “what is the standard of care for a non-lawyer who wants to practice law?” Think about that for a few minutes. It’s not easy.

Fred Ury told me the other day that he was just back from a hearing on California’s proposal to let non-lawyers into our fold, either as direct service providers or investors/partners in law firms. He thinks the idea has legs, driven by the access to justice issue. And he thinks if California does it, New York will follow for competitive reasons.

Some states already allow direct service by paralegals. D.C. allows non-lawyer partners in law firms, primarily, to allow former politicians to lobby as part of law firms and share in the wealth. Neither of these has caused too much change in how law is practiced by most of us. But if California and New York rewrite the rule book, they’ll change the equation for us all. Electrons don’t respect state boundaries, and the Internet is in every home. We’ll either have to change our rules to mirror theirs or become irrelevant.

This is either a great opportunity or a great threat. If you want to read more, the Winter 2019 issue of Daedalus, available for free, has 24 essays on this topic.

Mark Dubois was Connecticut’s first Chief Disciplinary Counsel. He’s on a leave from Geraghty & Bonnano of New London. He can be reached at [email protected].

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

ADVANCE Act Offers Conn. Opportunity to Enhance Carbon-Free Energy and Improve Reliability With Advanced Nuclear Technologies

Trending Stories

- 1Rejuvenation of a Sharp Employer Non-Compete Tool: Delaware Supreme Court Reinvigorates the Employee Choice Doctrine

- 2Mastering Litigation in New York’s Commercial Division Part V, Leave It to the Experts: Expert Discovery in the New York Commercial Division

- 3GOP-Led SEC Tightens Control Over Enforcement Investigations, Lawyers Say

- 4Transgender Care Fight Targets More Adults as Georgia, Other States Weigh Laws

- 5Roundup Special Master's Report Recommends Lead Counsel Get $0 in Common Benefit Fees

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250