Minneapolis Miracle: What We Can Learn from 'State of Nice' About Building Affordable Housing

Minneapolis is upfront about its land use pattern of racial segregation and has forcefully traced its origins back to the express racial discrimination embodied in racially restrictive covenants supported by zoning and public infrastructure decisions.

October 17, 2019 at 04:07 PM

6 minute read

Lessons for Connecticut were on display recently in Minneapolis.

Lessons for Connecticut were on display recently in Minneapolis.

They call it "Minnesota Nice" with varied explanations, mostly positive. Minnesotans are proud of their much-deserved reputation. I was there on Oct. 11, meeting with Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey, talking with him about Minneapolis 2040, the bold plan to break the back of the city's deeply rooted racial segregation.

We in the "Land of Steady Habits" can learn a great lesson from the dramatic and truly unprecedented action taken by Minneapolis in its plan recently approved by the Metro Council.

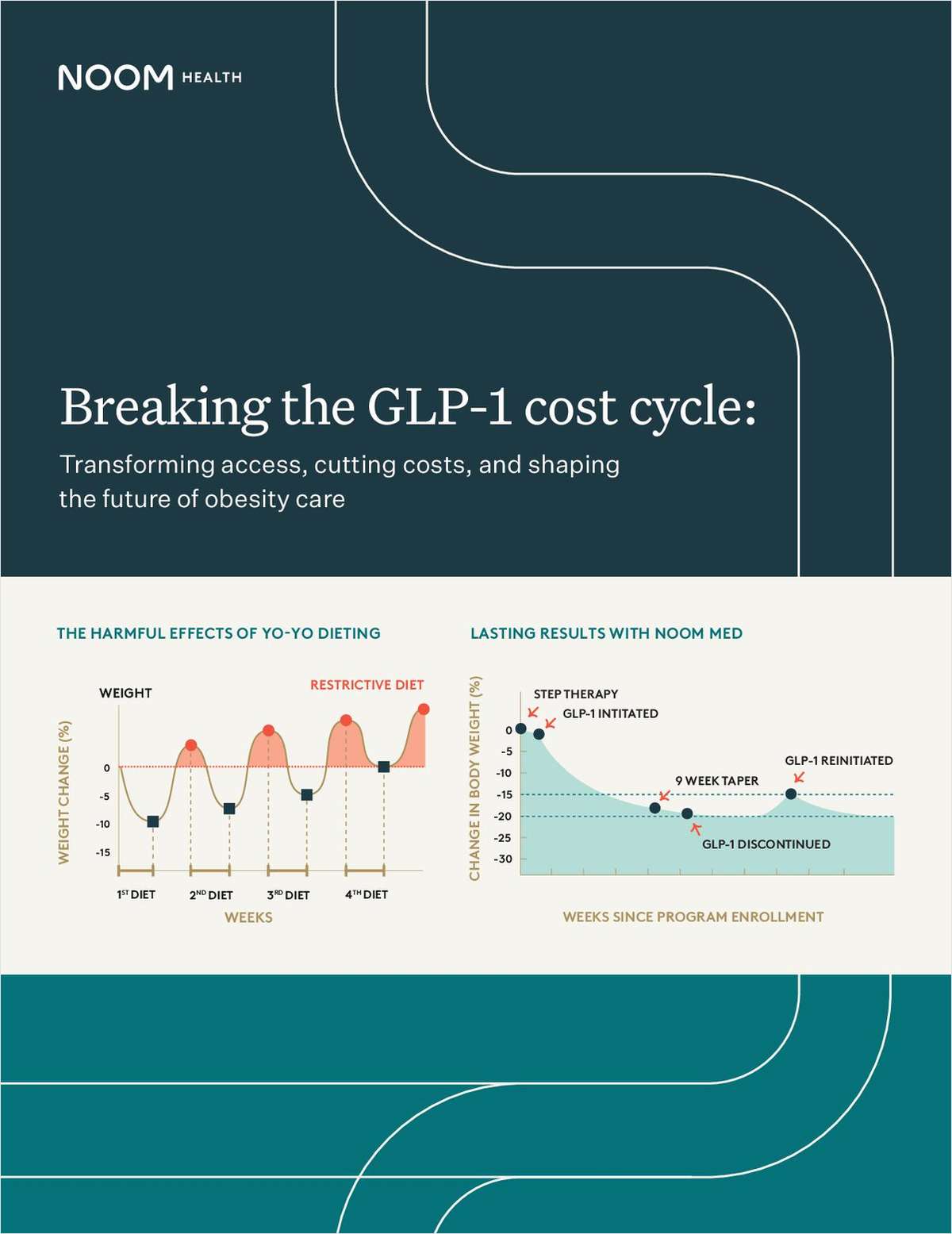

The city is upfront about its land use pattern of racial segregation and has forcefully traced its origins back to the express racial discrimination embodied in racially restrictive covenants supported by zoning and public infrastructure decisions. In February, MinnPost published an article detailing the history.

At a presentation by a member of the city's planning staff, I heard the most frank and open acknowledgment of the failure of public policy I have ever heard. They pull no punches on this issue of racial land use patterns in Minneapolis. Everyone I spoke with is totally focused on making it right. Frey is a strong leader, and his great leadership has been critically important.

The very first goal of the 1,100-page comprehensive plan is this:

"1. Eliminate disparities: In 2040, Minneapolis will see all communities fully thrive regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, country of origin, religion or zip code having eliminated deep-rooted disparities in wealth, opportunity, housing, safety and health."

The Brookings Institution described the plan in an article titled "Minneapolis 2040: The most wonderful plan of the year." The plan will build more housing by allowing as-of-right in-fill development in existing neighborhoods built out under current zoning, build housing that is less expensive by enabling large houses to be subdivided into multiple units, and build that less expensive housing in the better neighborhoods.

What is the key? What could one city, totally committed to making access to housing open and equal for all, possibly do in one fell swoop?

Minneapolis takes a three-part approach: 1. Increase building heights and densities for residential development near transit and employment centers. 2. Abolish parking requirements, as Hartford has so appropriately done.

And 3? The first book I wrote was in 1984, "Inclusionary Zoning Moves Downtown." In my more than four decades as a student-teacher and advocate of affordable housing, I never thought I would see this day. I never imagined government would have the foresight, political will and commitment to social justice to mandate, as Minneapolis has, that as-of-right in all single-family zones a property may be developed with duplexes or triplexes. This allows tripling the density in areas already developed, piggybacking on the sunk cost of the infrastructure. It's like getting free land and free utility hook-ups and no cost for streets, sidewalks and other infrastructure. It's all right there already. And when existing buildings are carved up, say a 3,000-square-foot house converted to three 1,000-square-foot apartments, there is no cost for the foundation and building envelope.

Connecticut's Affordable Housing Land Use Appeals Statute, Section 8-30g, enables the override of local zoning for affordable housing. It's been on the books for three decades, and a recent article reports the tally to date to be "about 5,000 affordable homes and more than 10,000 additional modestly priced, market rate apartments and homes as part of mixed-income developments." These are typically larger developments because they need the staying power for long, expensive legal battles that can go on for more than a decade. In Westport, an 8-30g battle has been fought since 2005—14 years without a final decision.

The late professor Terry J. Tondro of the University of Connecticut School of Law was co-chairman of the Blue Ribbon Commission on Housing, with Anita Baxter, the First Selectwoman of New Hartford. He has acknowledged that the Affordable Housing Land Use Appeals Statute was Fairfield County-centric and that one of its three purposes was to provide executive housing there: "Many large corporations have offices there, and were finding it difficult to lure executives to their headquarters because of the high cost of living in the county." Two other purposes he cited were providing more affordable housing generally and ensuring that children when they grew up could afford to live in the towns where they were raised.

The Affordable Housing Land Use Appeals Statute should continue, and could be strengthened in many ways, but it's not getting us far. It's almost a tokenism and if we rely on it alone, we won't get where we need to be. We think we're doing good with 8-30g. We're not, because we are hardly putting a dent in the problem. It makes some of us feel good, but that's not enough.

According to the U.S. Census, there are 892,621 single, detached housing units in Connecticut, out of a total 1,507,711 units. Let's say the governor and the General Assembly actually had the gumption to do what Minneapolis did and amend the state zoning enabling law to allow up to three units as-of-right. By the way, Oregon recently did essentially just that with House Bill 2001 enabling duplexes in many cases and even triplexes, fourplexes, attached townhomes, and cottage clusters on some lots. We need to ask ourselves: "So why don't we do the same?"

Back to those 892,621 Connecticut lots. If just 5% of those lot owners added a single unit and another 5% decided to add two units, we would have 44,631 and 89,262 units for a total of about 134,000 new housing units, most of them better sized and more affordable for the smaller households of today. The tremendous increase in supply would drive down housing prices across the board.

The Affordable Housing Land Use Appeals Statute has produced 5,000 units in 30 years; that's 167 units per year. Sure, we had a slow start and it takes years to get results, so generously triple that meager 167 to 500 units per year. With 8-30g it will take us, even at 500 units per year, 268 years to replicate what the Minneapolis plan would give us with a very laid back 5% and 10% participation.

What Minneapolis offers is something akin to the gig economy of affordable housing, like Airbnb is to short-term rentals and Uber is to ride hailing. Each and every homeowner can be a mini-developer. New housing will spring up everywhere. No litigation required. No deep-pocket developers required. No lawyers. No infrastructure costs. No land cost.

And a whole lot of happy homebuilders; but most importantly, a new era of diversity and inclusion all across our land.

Attorney Dwight Merriam practices in Simsbury and is a member of the Connecticut Law Tribune's editorial board.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trump Administration Faces Legal Challenge Over EO Impacting Federal Workers

3 minute read

Big Law Practice Leaders Gearing Up for State AG Litigation Under Trump

4 minute read

A Look Back at High-Profile Hires in Big Law From Federal Government

4 minute read

Legal Departments Gripe About Outside Counsel but Rarely Talk to Them

4 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250