Changes to US-Cuba Policy Signal Increased Cost of Due Diligence, Compliance

The Trump administration's prohibition of most transactions with a subset of Cuban persons or entities is not a novel idea with respect to the Cuban Assets Control Regulations (CACR), but it is one that adds additional complexity and transaction costs to an already Byzantine regulatory regime, as U.S. persons now need to undertake additional diligence before being able to undertake a transaction in Cuba, writes Rail Seonane.

July 21, 2017 at 08:57 PM

9 minute read

On June 16, the president announced the Trump administration's policy toward Cuba. The policy, among other things, seeks to “end economic practices that disproportionately benefit the Cuban government or its military, intelligence, security agencies or personnel at the expense of the Cuban people” by, with some exceptions, prohibiting direct financial transactions with entities that are under the control of or act for or on behalf of the Cuban military, intelligence or security services or personnel (such as Grupo de Administración Empresarial S.A. (GAESA)). In the coming weeks, the Department of the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) and the Department of Commerce will identify, and the Department of State will publish a list of, such “prohibited” entities.

The Trump administration's prohibition of most transactions with a subset of Cuban persons or entities is not a novel idea with respect to the Cuban Assets Control Regulations (CACR), but it is one that adds additional complexity and transaction costs to an already Byzantine regulatory regime, as U.S. persons now need to undertake additional diligence before being able to undertake a transaction in Cuba.

The CACR generally prohibits all transactions in which Cuba or a national thereof has a direct or indirect interest, unless such transaction is licensed by OFAC or is otherwise exempt. Licenses could be in the form of (1) “general licenses,” exceptions to the CACR's general prohibitions, which exceptions are an express part of the CACR or (2) “specific licenses,” tailored licenses requested by a party whose proposed transaction does not meet the specifications of a general license.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Attorney Emerges as Possible Owner of Historic Miami Courthouse Amid Delays of New Building

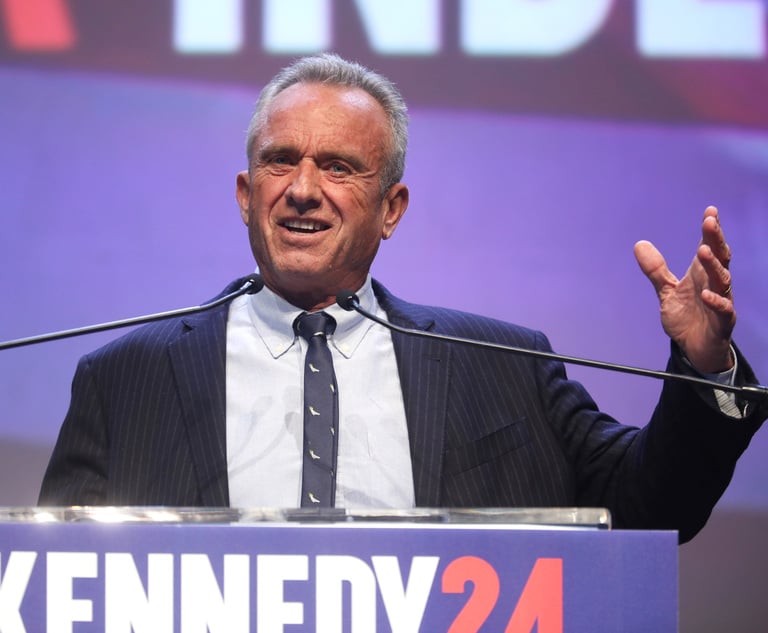

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute read

US Judge Cannon Blocks DOJ From Releasing Final Report in Trump Documents Probe

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 2No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 3Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 4Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

- 5Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250