Attorneys' Attempt to Paint a Picture in Complicated Foreclosure Case Fails to Clarify Ownership

The debt had changed hands at least five times with the sloppy documentation, leaving attorneys to try to follow a maze of ownership.

December 06, 2017 at 03:30 PM

4 minute read

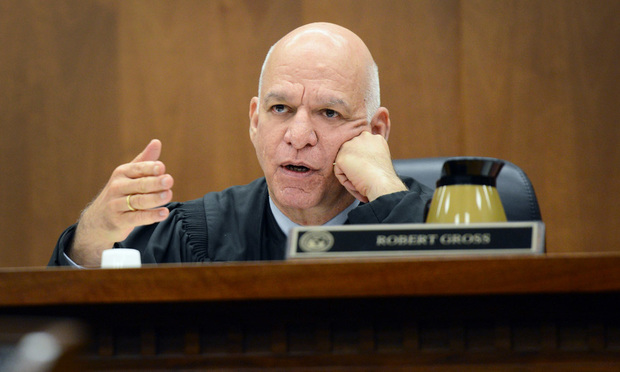

Photo by Melanie Bell.

A mortgage that was “passed around like the flu” seemed to send two South Florida courts down a rabbit hole as a successor creditor with multiple predecessors tried to prove legal standing to foreclose on the property.

It was so complicated, the appellate court noted that the mortgage company's attorneys' “valiant effort” to map out the chain of ownership resulted in a labyrinth of “different types of arrows pointing in all directions.”

Plaintiffs looking to collect on a defaulted real estate debt must prove their right to do so. But by the time the suit came before Florida's Fourth District Court of Appeal, a mangled chain of ownership left judges to decipher who owned a debt that had traded at least half a dozen times on the secondary market.

“In this mortgage foreclosure case, the underlying mortgage was passed around like the flu, giving rise to a complexity of ownership that frustrated the appellee's attempts to demonstrate standing at trial,” Fourth District Judge Robert M. Gross wrote in the unanimous decision issued Wednesday with Judges Melanie G. May and Mark Klingensmith.

Court records suggest Thomas Wade Young and Joseph B. Towne of Lender Legal Services LLC in Orlando created a thorough work product—but perhaps with a level of detail that did nothing to simplify their position.

“To the answer brief, the appellee attached a chart of the ownership lineage of the

mortgage and note, with different types of arrows pointing in all directions—a valiant effort which demonstrated that the transfer history here defies pictorial representation,” Gross wrote for the appellate court.

The case pitted appellant and homeowner Marcia Supria against creditor Goshen Mortgage LLC. It involved a maze of parties that ended with Goshen substituting for the original plaintiff, Christiana Trust, a division of Wilmington Savings Fund Society FSB, as trustee for Stanwich Mortgage Loan Trust's series 2012-13.

By the time Goshen entered the picture, court records suggest the debt had changed hands at least five times. But with the sloppy documentation typical of the period of brisk trading during the last housing market collapse, it was difficult to trace clear changes in ownership.

“It's been well-known among the foreclosure bar, both on the plaintiffs bar and the defense bar, that the Fourth DCA is very strict in requiring evidence of standing,” said McGlinchey Stafford member Manuel Farach, who was not involved in the litigation but sits on the Florida Bar's executive council for the Real Property and Business Law Sections. This case is an indication of that.”

The judicial panel found the first transfer invalid because no evidence supported the assignor's authority to give ownership of the debt to another party. The second also fell short, this time because the court saw no proof the assignor had a transferable interest. The third and fifth were both flawed, transferring the mortgage but not the promissory note.

In the end, the Fourth DCA disagreed with Broward Circuit Judge Kathleen D. Ireland, who'd sided with Goshen. It instead found the financial institution had failed to prove standing and remanded the case for a judgment in the homeowner's favor.

The ruling was a victory for foreclosure defense attorneys, but some members of the plaintiffs bar suggest such decisions do more to cool trading of real estate debt than to protect consumers.

“It appears there were some abuses at some point in the past in terms of how people were endorsing instruments,” Farach said. “I just haven't seen a lot of concrete examples or situations where this has been a problem. There've been hundreds of thousands of foreclosures in Florida. I haven't seen a single case where two people were claiming ownership of a note. If this were a huge problem then we would have seen not just one but several cases.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

South Florida Real Estate Lawyers See More Deals Flow, But Concerns Linger

6 minute read

Vedder Price Shareholder Javier Lopez Appointed to Miami Planning, Zoning & Appeals Board

2 minute read

Real Estate Trends to Watch in 2025: Restructuring, Growth, and Challenges in South Florida

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Apply Now: Superior Court Judge Sought for Mountain Judicial Circuit Bench

- 2Harrisburg Jury Hands Up $1.5M Verdict to Teen Struck by Underinsured Driver

- 3Former Director's Retaliation Suit Cleared to Move Forward Against Hospice Provider

- 4New York Judge Steps Down After Conviction for Intoxicated Driving

- 5Keys to Maximizing Efficiency (and Vibes) When Navigating International Trade Compliance Crosschecks

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250