Court Affirms Dismissal of Tobacco Cases Because of Dead Clients

Thursday's decision came less than four months after a federal court slapped a $9 million sanction on Jacksonville-based Farah & Farah and The Wilner Firm “to account for the immense waste of judicial resources by maintaining over a thousand non-viable claims.”

February 09, 2018 at 02:43 PM

5 minute read

A state appellate court upheld the dismissal of more than 70 lawsuits against tobacco companies and refused to allow attorneys to amend the complaints because the clients had died before the cases were filed.

Thursday's decision came less than four months after a federal court slapped a $9 million sanction on Jacksonville-based Farah & Farah and The Wilner Firm, as well as their principals, Charlie Farah and Norwood Wilner, “to account for the immense waste of judicial resources by maintaining over a thousand non-viable claims.”

The lawsuits stemmed from a 2006 Florida Supreme Court ruling that established findings about a series of issues, including the dangers of smoking and misrepresentation by cigarette makers. The ruling helped spawn thousands of lawsuits in state and federal courts, with plaintiffs able to use the findings against tobacco companies. The lawsuits have become known as “Engle progeny” cases.

After the 2006 ruling, Wilner and Farah filed approximately 3,700 Engle progeny cases in Florida state and federal courts, according to court documents.

But in the decision Thursday, the state's First District Court of Appeal upheld a lower-court decision to dismiss 73 of the cases because the clients were dead.

After the cases were filed, the lawyers “then waited eight years to backfill the case with legitimate plaintiffs and claims for the very first time,” Judge Timothy Osterhaus wrote in an eight-page opinion joined by Judges Clay Roberts and M. Kemmerly Thomas.

The three-judge panel found that a Duval County circuit judge was right to refuse to allow the lawyers to amend the complaints to substitute their dead clients' estates or survivors, if any exist.

“Florida's preference for deciding cases on the merits says nothing of requiring courts to perpetuate hollow, uninvestigated lawsuits filed by counsel on behalf of dead people,” Osterhaus wrote.

The court also scolded the plaintiff lawyers for failing to confirm the allegations made in the complaints, something they were obligated to do.

Wilner, Farah and their law firms had as much time as other attorneys to investigate their clients' claims, locate survivors and join relevant estates and personal representatives to lawsuits before a January 2008 deadline for the Engle progeny cases, Osterhaus pointed out. The deadline was set by the Florida Supreme Court.

“But plaintiffs' counsel didn't verify their claims before filing them. Instead, they alleged patently false things, such as that the plaintiffs' injuries and losses were 'continuing (and would) be suffered into the future.' Then, once the cases were filed, they let the cases sit on the court's docket for almost eight years, still without checking with their 'clients' or their estates to verify the allegations and amend them if necessary,” Osterhaus wrote. “Plaintiffs' counsel ultimately left it to the court to flush out the truth about their supposed clients and their non-viable claims.”

In a telephone interview Thursday, Wilner disputed the conclusions reached by the appellate court.

Wilner told The News Service of Florida he filed the cases on behalf of clients who had come to his office, in some instances more than a decade before the Engle progeny cases were filed.

“When they came to see us, they were quite alive. We had no way of knowing they were not alive. We tried to preserve their claims as best as we could,” Wilner said. “We've always erred on the side of the clients. We're disappointed that the court didn't agree with us, but we tried to get these people some compensation for their injuries.”

Wilner and the other lawyers are appealing the $9 million sanction imposed by a four-judge federal court panel in October. The lawyers are arguing, among other things, that the sanction is unconstitutionally excessive.

In the Oct. 18 ruling, the federal district judges blasted Wilner and Farah for a variety of wrongdoing, including filing lawsuits on behalf of dead clients.

“As it turns out, many of the plaintiffs never authorized Wilner and Farah to file a suit. Some had barely heard of them,” the federal judges wrote in the 148-page order issued Oct. 18.

Over 500 of the plaintiffs were people who had died well before the lawyers filed the complaints, including one who had died 29 years earlier, the court noted.

A judge learned of the dead plaintiffs in 2012 only after sending questionnaires directly to the named plaintiffs, over the lawyers' objections, according to the opinion.

“It was this obstructive, deceptive, and recalcitrant behavior that, in combination with the hundreds of frivolous complaints, compelled the court to initiate sanctions proceedings,” U.S. District Judges William Young, Timothy Corrigan, Marcia Morales Howard and Roy Dalton Jr. wrote in the order.

But Wilner also rejected the federal judges' findings, saying his office had “documentation for every single person that came in here.”

“What sometimes happened is, Mr. Smith comes into this office in 1998, and believe me they did, and they came in with their oxygen and they came in with their wheelchairs and they came in dying in front of us, and we said absolutely we'll sign you up. And then unbeknownst to us they die. We never could find who might be left because they were the ones who signed up,” Wilner said. “So, 10 years later, the wife or the daughter says, 'I don't know anything about this case.' No, you don't because it was Mr. Smith who came in here and we did the best we could.”

Dara Kam reports for The News Service of Florida.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Holland & Knight Hires Former Davis Wright Tremaine Managing Partner in Seattle

3 minute read

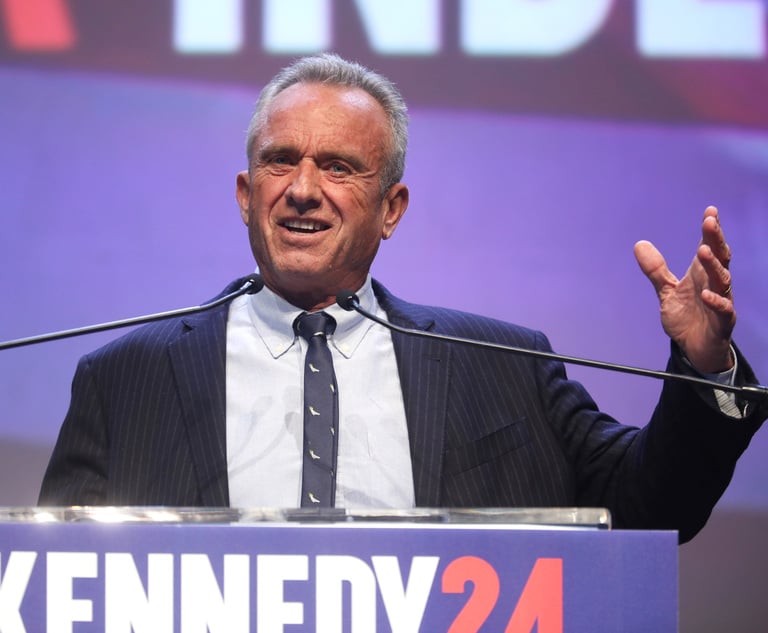

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute read

Plaintiffs Attorneys Awarded $113K on $1 Judgment in Noise Ordinance Dispute

4 minute read

Local Boutique Expands Significantly, Hiring Litigator Who Won $63M Verdict Against City of Miami Commissioner

3 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250