Sticky Fingers: Attorney Thefts from Clients Spiked in Great Recession

The last recession saw a significant increase in Florida disbarments for stealing and other serious trust account violations.

March 09, 2018 at 11:54 AM

10 minute read

The Great Recession left a wake of disbarred attorneys in Florida who lost their licenses after dipping into client trust funds in order to keep their practices afloat.

Florida Bar data reviewed by the Daily Business Review showed client theft-related disbarments after the recession increased by nearly 88 percent, peaking at 47 disbarments in 2010. It often takes a year or more for the state Supreme Court to issue a final disciplinary order once the Florida Bar is notified of a possible trust account violation. That means disbarments for recession-era conduct came slightly after the economic downturn.

The recession lasted from December 2007 through June 2009, according to the nonprofit National Bureau of Economic Research. Many attorneys lost business during the recession as companies and families struggled to balance their checkbooks.

“This was the height of the financial crisis in Florida, and it gave rise to discipline cases for trust account violations as well as issues involving consumer fraud,” the bar said in a statement.

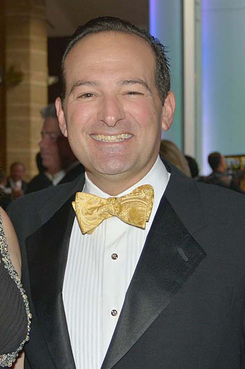

Given that there are more than 106,000 attorneys in Florida, the number of those who stole from clients during the recession is minuscule. But following the bar's client trust account rules is sacrosanct—and any violations cut to the heart of the profession, said Florida Bar Board of Governors member Dennis Kainen.

“If members of the public can't rely on their lawyers, then the profession will ultimately cease to exist as we know it,” said Kainen, a partner at Weisberg Kainen Mark in Miami.

What Causes Lawyers to Steal?

When money gets tight, some lawyers think they can dip into their client trust accounts—just for $10,000 or so, until they can pay their bills.

“They'll move money over, thinking in a couple days they're going to replenish it,” said Miami attorney Andrew Berman, who represents lawyers facing bar complaints. “Often, they don't.”

After the first theft, “the seal is broken,” the Young, Berman, Karpf & Gonzalez senior partner said. Subsequent ”borrowing” gets easier and easier, until the attorney is too far behind to make up the difference.

Jack Weiss, a bar discipline defense lawyer in Tallahassee, also said the few cases he's seen in the past decade involving severe trust account violations have been “a direct result of [lawyers] using their trust account as an interest-free loan account.”

“That's grossly improper,” said Weiss, of counsel at Rumberger Kirk & Caldwell. “You just don't do that.”

Other times, attorneys who steal aren't squeezed for cash at all—they just think they can get away with it, defense lawyers said.

Particularly for real estate and personal injury attorneys, who often have six- or seven-figure trust account balances, it can be a while before a bounced check or a client complaint tips off the bar to a possible problem. Banks report insufficient funds in client trust accounts directly to the Florida Bar.

For instance, Fort Myers attorney Joseph Troiano agreed to disbarment in February 2010, shortly after SunTrust Bank sent five notices of insufficient funds in the firm's trust account in one week. One client who had $450,000 held in trust could not clear a $10,000, according to the bar.

It turned out the real estate and tax attorney took about $2.5 million from the trust account, according to his plea agreement in criminal court. Troiano was investing client funds in a Costa Rican real estate project, a scheme that began in 2008, according to the indictment.

Stealing from trust accounts is also more common among solo practitioners and small firms, particularly given a 2014 bar rule amendment making each lawyer in a firm responsible for reporting knowledge accounting issues.

“I can't say I've ever seen a firm where two people got their hands in the cookie jar,” said Kevin Tynan, a Tamarac attorney with Richardson & Tynan, who began defending lawyers in 2000 after 13 years as Florida Bar counsel.

When a lawyer does decide to steal, it's usually not to keep the practice afloat, said Miami legal malpractice defense attorney Brian Tannebaum.

“Lawyers have an identity,” he said. “That identity is of a person with a certain level of status in society. A lot of lawyers build their lives around that, so you'll find lawyers who have very expensive cars, very expensive homes, very expensive lifestyles.”

Lawyers' egos sometimes prevent them from facing the music, said Tannebaum, special counsel to Bast Amron.

“I've spoken to lawyers who have said, 'I have all these expenses, all these bills, and I couldn't tell my family I wasn't making X-amount of dollars anymore because of the recession,'” he said.

Preparing for the Next Recession

Hard economic times will surely come again—so what can the bar do to prevent as many lawyers as possible from stealing from clients?

A bar committee spent hundreds of hours studying that question back in 2010, soon after the recession and in the wake of a $1.2 billion Ponzi scheme conducted by disbarred Fort Lauderdale lawyer Scott Rothstein, who's serving a 50-year prison sentence. The scheme involved investments in fake legal settlements, but Rothstein's disbarment order noted he was also accused of stealing from client trust accounts.

Random audits were one idea considered by the the Clients' Security Fund Review Committee II, chaired by West Palm Beach attorney and 2014-2015 Florida Bar President Gregory Coleman. Bar associations in some states, including Connecticut and North Carolina, conduct random audits of trust accounts. In Iowa, auditors review all attorney trust accounts on a regular basis.

But the idea didn't make sense for Florida, the third-largest mandatory bar in the country, Coleman said.

“First of all, who's going to pay for it?” the Critton Luttier Coleman partner said. “The bar can't afford to hire an auditing firm to go around the state and audit lawyers' trust accounts. It would not be fair to ask the lawyer to do it because … 75 percent or more of our [Florida] lawyers practice in firms of 10 lawyers or less. More than a third are solos. Even $2,000 for a solo practitioner to audit their trust account is a lot of money.”

The committee, which focused on Florida's Clients' Security Fund used to help repay victims of attorney theft, also considered mandatory legal malpractice insurance or surety bonds.

“Very quickly, the bonding and insurance companies turned around and said, 'Thanks, but no thanks. We really don't have an interest in this,'” Coleman said. “It was too hard to underwrite … There were no algorithms designed for this type of risk.”

In the end, the committee decided the most doable action is to provide free trust accounting education through Lawyers Advising Lawyers. The program focuses on helping young attorneys through various challenges, such as starting their own firms, which many law grads did during the recession as law firms cut back on hiring.

“We threw in a little, 'Hey, by the way, if you want to keep your law license, don't even think about [stealing],'” Coleman said. ”I don't know to what degree that did or didn't help, but it was probably the best we could do at that time, just because of the sheer number of lawyers.”

The bar's current project in the trust account realm is testing software lawyers can use to set up and manage clients' accounts. The program automatically does the accounting work to keep attorneys in compliance with bar regulations. It would make theft by law firm employees more difficult because of password protection and keystroke tracking, the project's leader, Andy Sasso, told the Florida Bar News.

It's also possible the bar's increased focus on mental health, including the creation of a committee devoted to the issue, could help prevent some instances of theft.

Lawyers disciplined for serious trust account violations are sometimes battling mental health issues, such as addiction to alcohol, drugs or gambling, that are funded with stolen client money, according to defense attorneys. But it's important to remember the relationship between theft and mental health is “complex,” Tannebaum said.

Defense attorneys also said they have noticed more thorough Florida Bar investigations since the Rothstein fraud, with relatively small trust account mistakes drawing closer scrutiny.

“The response used to be, 'OK, don't do it again.' Now the response is, 'Well, we need to see three to six months of bank statements [and] trust account records,'” Tannebaum said.

A Florida Bar spokesperson said the disciplinary investigation process has not changed since Rothstein.

“The Bar investigates each potential trust accounting violation by conducting an audit pursuant to the Rules Regulating The Florida Bar,” a bar statement said. ”Following a review of the discipline system in 2012 by the Hawkins Commission, revised communications procedures were put in place regarding high-profile cases to keep the public and members better informed.”

The Florida Supreme Court appears to be handing out harsher discipline for inadvertent trust account violations in recent years, attorneys interviewed for this story observed—although the punishment for stealing has remained constant.

“I can tell you that lawyers who take money out of their trust account intentionally, lose their license, whether it's $15 or $15 million,” Coleman said. “It's the death penalty. … You touch trust account money, you're dead, you're toast, you're history.”

A Different Choice

If all else fails, lawyers facing financial hardship might do well to remember one principle: karma.

Miami attorney Jim Ferraro is a strong believer in “what goes around comes around.” The Ferraro Law Firm founder had just hung his shingle representing football players back in 1987 when he found himself under “tremendous financial strain,” he recalled in his book “Blindsided.” No new business was coming in because of negative publicity from a high-profile client's arrest.

“To stay alive and make payroll, I maxed out my one and only credit card for $5,000 and borrowed $5,000 from my old buddy Hercules,” Ferraro wrote in the 2017 book.

One day, Ferraro received a $3,000 insurance refund check for his client Eddie Brown, the 1985 NFL Rookie of the Year. The check was made out to Ferraro by mistake.

“I was so desperate for money that I very seriously considered depositing it into my account,” Ferraro wrote. “I was financially at rock bottom. There wasn't a chance Eddie would ever know what I had done. I thought long and hard about how badly I needed that money, and naturally assured myself I'd pay it back to him someday. I had the check in my sweaty hand, literally staring at it for several minutes.”

Then Ferraro decided he couldn't live with himself if he stole the money. He picked up the phone, called Brown and deposited the check into his client's account.

“Within three years, four at the most, of having the check in my hand, I was making more money than I've ever seen in my life,” Ferraro told the Daily Business Review.

The opportunity came along in 1988 for Ferraro to get into asbestos litigation, and he started bringing in seven figures annually. Today, his firm is nationally recognized for its mass tort work. The once-broke attorney recently bought a $21.5 million penthouse condo on Fisher Island.

Ferraro said there's no doubt in his mind that if he had stolen Brown's check, he would never have gotten caught—but his life would have gone a totally different way.

“It doesn't matter what religion you are,” the attorney said. “It's a karmic type of thing.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

US Judge Dismisses Lawsuit Brought Under NYC Gender Violence Law, Ruling Claims Barred Under State Measure

No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

5 minute read

Second DCA Greenlights USF Class Certification on COVID-19 College Tuition Refunds

3 minute read

Florida Law Firm Sued for $35 Million Over Alleged Role in Acquisition Deal Collapse

3 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250