Plaintiffs Lawyers in FIU Bridge Collapse Race to Answer Urgent Questions

Law firms of various sizes and strategic approaches are deciding how much to collaborate as they investigate the March 15 collapse.

March 30, 2018 at 12:27 PM

5 minute read

Investigating what caused the pedestrian bridge collapse near Florida International University will be a massive undertaking — and now the victims' lawyers must decide how much, or how little, they want to work together.

Six lawsuits have been filed or announced against the construction and engineering companies that worked on the bridge, and more are likely to follow on behalf of the six killed and several others injured in the March 15 collapse.

Some firms were off to the races immediately, with the 350-lawyer firm Morgan & Morgan putting investigators on the ground while cleanup was still underway north of the campus on Southwest Eighth Street near 109th Avenue. The firm filed the first two lawsuits on behalf of Marquise Hepburn and Emily Panagos and named four companies as defendants.

Four-attorney Miami firm Lagos & Priovolos, which represents the widow and son of Rolando Fraga, took a different tack in suing only the two key players to start: Munilla Construction Management and FIGG Bridge Engineers.

“From the available knowledge that I have, I file what I know I can take to trial within a very short period of time,” partner Christos Lagos said. “I don't like to allege things that might be difficult or impossible to figure out for a long period of time.”

The varying firm sizes, strategies and client interests involved in the case will mean some divergence in discovery efforts, but all the plaintiffs lawyers interviewed for this article expressed interest in coming together to work as a team. Attorneys from the five firms involved so far — Morgan & Morgan, Lagos & Priovolos, Aronfeld Trial Lawyers, Grossman Roth Yaffa Cohen and Collazo Law Firm — have not yet held a meeting.

Attorneys Yesenia Collazo of the Collazo Law Firm and Spencer Aronfeld of Aronfeld Trial Lawyers did not respond to requests for comment by deadline.

Miami-Dade Circuit Court will almost certainly consolidate some forms of discovery. “The defendants will not tolerate seven or eight different law firms doing the same depositions over and over again,” said Stuart Grossman of Grossman Roth in Coral Gables, which filed suit Thursday on behalf of injury victim Richard Humble.

But when it comes to hiring experts and investigating what might have gone wrong with the design, construction, installation and testing, each firm is carving its own path.

“We are concerned that other claimants may attempt to utilize inappropriate tests or flawed portions of tests performed which could lead to inaccurate or misleading results,” Morgan & Morgan attorney Matt Morgan of Orlando said in an email. “Credibility is paramount. Flawed testing or analysis, which may initially appear favorable, can and will have disastrous results at trial.”

Attorneys also said that while they will be interested in the results of investigations by the National Transportation Safety Board and law enforcement, they “have neither the need nor desire to wait for anyone else,” as Morgan put it.

“We will, of course, utilize information obtained by the NTSB during their investigation, especially their physical examination of evidence not otherwise available to us,” he said. “We anticipate various other portions of their reports will be helpful, but we reserve the right to disagree with erroneous conclusions as we have done in the past.”

The questions to answer in discovery are numerous: Why was the novel “quick-build” approach used for the bridge? How much was politics involved in the bid process? How did the Florida Department of Transportation handle a call reporting cracks in the bridge? And, of course, why was bridge testing done in the middle of the day with traffic flowing underneath?

“That's the burning question in our community — why would they put the public at this risk of unnecessary harm when they could have stopped the project?” Lagos said.

Grossman said the case reminds him in many ways of the Miami Dade College parking garage in Doral, which also had not yet opened when it collapsed in 2012. Grossman represented plaintiffs in that litigation as did Alan Goldfarb and the late Ervin Gonzalez.

The plaintiffs attorneys in that case worked together from the start to “map [the case] out in an orderly fashion,” Grossman said. Ultimately, the key to the settlement of those cases was really not the plaintiffs lawyers, but the defendants, he said.

“In my estimation, once they're done futzing around with each other in terms of who's responsible for this, who's responsible for that, they will probably — if they're smart — not want to litigate this,” Grossman said. The defendants “will want to try to come up with a pool [of money] as if it were a plane crash and call us in and say, 'OK, let's all get together and do this.' “

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

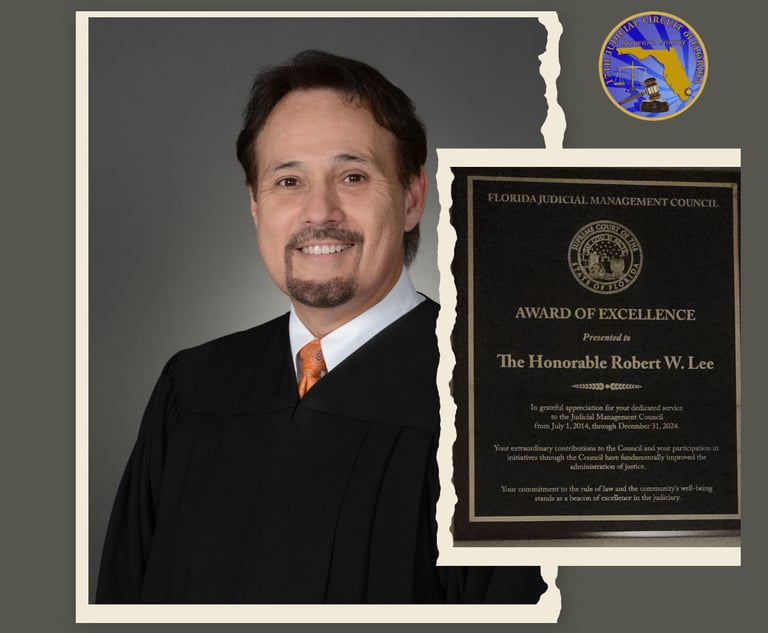

Trailblazing Broward Judge Retires; Legacy Includes Bush v. Gore

Trending Stories

- 1The Key Moves in the Reshuffling German Legal Market as 2025 Dawns

- 2Social Media Celebrities Clash in $100M Lawsuit

- 3Federal Judge Sets 2026 Admiralty Bench Trial in Baltimore Bridge Collapse Litigation

- 4Trump Media Accuses Purchaser Rep of Extortion, Harassment After Merger

- 5Judge Slashes $2M in Punitive Damages in Sober-Living Harassment Case

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250