Judge Hammers State Over Methadone Center Applications

Pointing to an arbitrary process that “ignores substance in favor of blind luck,” an administrative law judge rejected a state emergency rule drawn up to help license more methadone-treatment centers across Florida.

April 27, 2018 at 12:41 PM

3 minute read

Pointing to an arbitrary process that “ignores substance in favor of blind luck,” an administrative law judge rejected a state emergency rule drawn up to help license more methadone-treatment centers across Florida.

Judge R. Bruce McKibben, in a 44-page order, hammered a process in which the Department of Children and Families accepted applications for the licenses on a first-come, first-served basis. The News Service of Florida reported in December that the process led to applicants camping out at the department's headquarters to be first in line.

The process led to only a handful of providers getting applications accepted, while others were shut out, resulting in the legal challenge.

“The system for accepting applications on a first-come, first-served basis is arbitrary,” McKibben wrote. “It is illogical to assume that the first applications filed, containing scant information, are equal or superior to later filed applications. This scheme contravenes the basic expectation of law for reasoned agency decision making.”

The DCF issued the emergency rule last year as officials looked to increase the number of methadone clinics in the state as part of a $27 million federal grant aimed at curbing opioid addiction and overdoses. In all, the department on Oct. 2 accepted 49 applications for clinics in 48 counties, with the successful applicants then able to seek licensure, according to McKibben's order.

But 20 of the applications were approved for one provider, Psychological Addiction Services LLC, while another 19 were approved for Colonial Management Group L.P., and eight were approved for Relax Mental Health Care. Two other applicants each received one approval.

Dacco Behavioral Health Inc., Operation Par Inc. and Aspire Health Partners Inc. challenged the emergency rule, with other organizations also intervening in the case.

McKibben's order focused heavily on what he described as the first-in-line “scheme” as being arbitrary. He said the department acknowledged that “if the first person in line had filed applications for all 49 new clinics, all the other applicants would have been denied the right to seek licensure.”

“The department felt that allowing applications to be submitted via email would potentially crash its email system, so email submission was not allowed,” he wrote. “The applications received first by the department were to be approved, notwithstanding any substantive shortcomings or comparative failings of those applications as compared to applications received later. No other criteria were considered; first was deemed best. What is fair about approving competing applications based on who filed first rather than on substantive differences in the services being proposed?”

McKibben also wrote that the process could slow down the opening of clinics because of the logistics and expense involved in opening multiple facilities.

“It is more likely that a single entity receiving approval for multiple new clinics might 'bank' the approvals, expending time and money for only a few at a time, at best,” he wrote. “If so, that could result in far fewer new clinics coming on line than the 49 projected by the department under the emergency rule. As the applications contained no requirement to provide financial information, it is impossible for the department to determine whether the approved entities, which received multiple approvals, could successfully — and timely — complete their projects. There is no specific time frame for which a granted applicant must commence operations once approved.”

Jim Saunders reports for the News Service of Florida.

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Auto Dealers Ask Court to Pump the Brakes on Scout Motors’ Florida Sales

3 minute read

Saul Ewing Loses Two Partners to Fox Rothschild, Marking Four Fla. Partner Exits in Last 13 Months

3 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Parties’ Reservation of Rights Defeats Attempt to Enforce Settlement in Principle

- 2ACC CLO Survey Waves Warning Flags for Boards

- 3States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 4Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

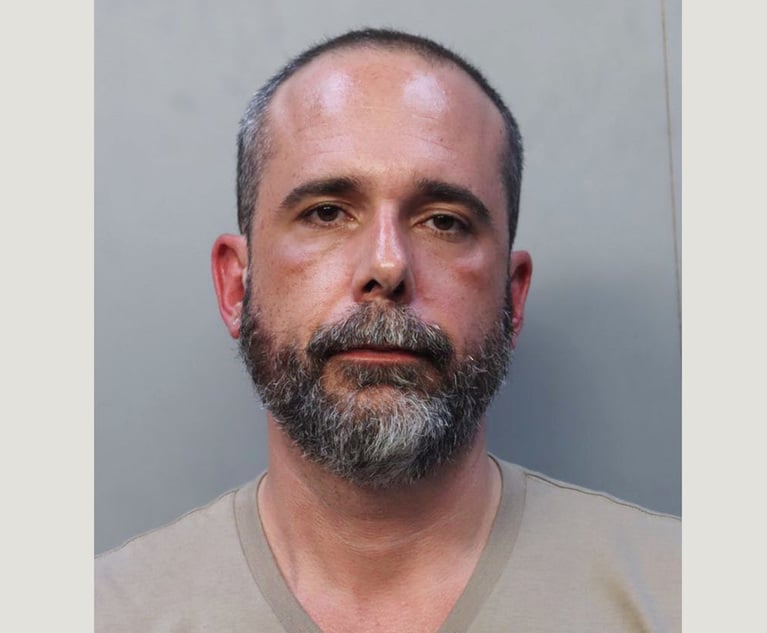

- 5Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250