Federal Appeals Court Rules Substitute Teachers Can Be Subject to Drug Testing

The School District of Palm Beach County's policy for hiring substitutes was challenged as violating applicants' Fourth Amendment protections from unreasonable search and seizure.

December 26, 2018 at 06:22 PM

4 minute read

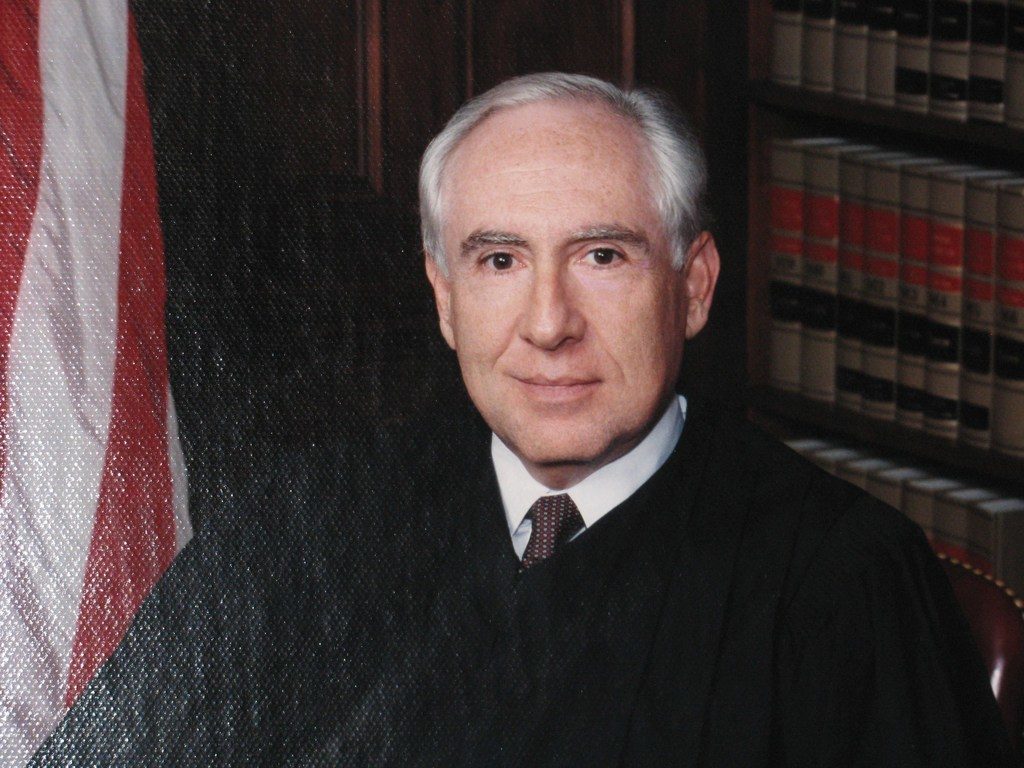

Judge Stanley Marcus of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit. Courtesy photo

Judge Stanley Marcus of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit. Courtesy photo

A federal appeals court has ruled that a South Florida school district has not violated the Fourth Amendment by mandating drug testing for substitute teachers.

Judge Stanley Marcus of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit held that the School District of Palm Beach County “has a sufficiently compelling interest” to screen possible substitute teachers for drug use. “The School Board has not violated the constitutional mandate barring unreasonable searches and seizures,” he wrote.

The plaintiff in the case, Joan Friedenberg, brought a civil rights complaint against the Palm Beach County School District after she refused to submit the drug tests mandated by the school district for employees and volunteers. Her case was brought before Marcus following an appeal, as the district court ruled that “the balance of interests strongly favored the policy of suspicionless testing of substitute teacher applicants.”

The judge was joined in his opinion by Chief Judge Ed Carnes and Judge David Ebel. The panel found that public schools enjoy “unique circumstances” for perceived intrusions upon privacy and protection from unreasonable searches and seizures.

Read the opinion:

“Suspicionless searches are permissible in a narrow band of cases where they serve sufficiently powerful and unique public needs. The force of these needs depends heavily on the context in which the search takes place,” the opinion held. “As we see it, ensuring the safety of millions of school children in the mandatory supervision and care of the state, and ensuring and impressing a drug-free environment in our classrooms, are compelling concerns.”

The opinion emphasized the need for substitute teachers—like other school district employees—to be able to flexibly and reliably ensure students' safety under sometimes-intense and volatile circumstances.

“If schools are going to be able to handle emergencies that threaten children's safety, teachers will need to be able to identify and respond to emergencies quickly, decisively, and with sound judgment,” Marcus wrote. “As acute situations arise, and we know they will, the danger posed by leaving children, especially young children, in the care of an intoxicated teacher is profound. A teacher under the influence of drugs is significantly less likely to respond promptly, efficiently, and with sound judgment than a sober and clearheaded teacher.”

“This testing regime, we think, provides the kind of immediate—that is, proximate—response to the threat posed by drug-using teachers,” the opinion continued. “The school district could reasonably conclude, as it obviously did, that testing at a later date, after a problem is uncovered and while a substitute is already standing in the front of a classroom, would not adequately protect schoolchildren.”

The court ultimately ruled that the school district's policy posed a “minimal intrusion” upon the plaintiff's privacy interests and affirmed the lower court's denial of a preliminary injunction.

James K. Green, a West Palm Beach attorney who served as Friedenberg's counsel, expressed disappointment with the ruling in a statement provided to the DBR.

“We appreciate the thought given by Judge Marcus to our arguments, but respectfully disagree that, on this record, there is 'a diminished privacy interest owing to the unique Fourth Amendment context of the public schools,'” the statement read.

Requests for comment from Adam Wolf, Green's co-counsel, were not returned by press time. Nancy Gbana Abudu of the American Civil Liberties Union of Florida and West Palm Beach lawyer Nancy Udell were also listed as the plaintiff's legal representation, and did not respond to the DBR by deadline.

The litigators employed by the School District of Palm Beach County—Jean Middleton, Sean Fahey and Shawntoyia Bernard—also did not respond by press time.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Read the Document: DOJ Releases Ex-Special Counsel's Report Explaining Trump Prosecutions

3 minute read

US Judge OKs Partial Release of Ex-Special Counsel's Final Report in Election Case

3 minute read

Special Counsel Jack Smith Prepares Final Report as Trump Opposes Its Release

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Settlement Allows Spouses of U.S. Citizens to Reopen Removal Proceedings

- 2CFPB Resolves Flurry of Enforcement Actions in Biden's Final Week

- 3Judge Orders SoCal Edison to Preserve Evidence Relating to Los Angeles Wildfires

- 4Legal Community Luminaries Honored at New York State Bar Association’s Annual Meeting

- 5The Week in Data Jan. 21: A Look at Legal Industry Trends by the Numbers

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250