How No-Nonsense Litigator Michael Budwick Curbs the Damage Caused by Ponzi Schemers

There's never a dull day at Meland Russin & Budwick in Miami, where Budwick is charged with cleaning up the legal and financial mess left by Ponzi schemers nationwide.

January 11, 2019 at 01:53 PM

7 minute read

Michael Budwick, with Meland Russin & Budwick in Miami. Courtesy photo.

Michael Budwick, with Meland Russin & Budwick in Miami. Courtesy photo.

Miami commercial litigator Michael S. Budwick has outwitted many a conman in his time, and Tom Petters — behind the third biggest Ponzi scheme in U.S. history — was no exception. Here's how he does it.

When Budwick comes on the scene, the damage has been done, and all that's left to do is pick up the pieces. But of course, it's never that simple.

Budwick once represented the trustee in a bankruptcy case involving Claudio Osorio, a Venezuelan business tycoon who lived on Star Island in Miami until he was brought down for multimillion-dollar fraud operation.

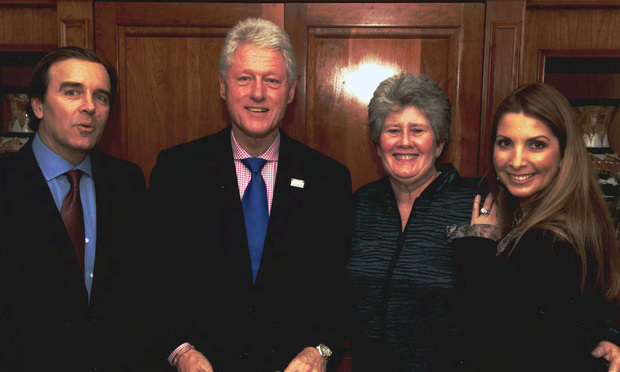

Partway through the case, Budwick noticed an interesting picture on Osorio's office wall. Alongside Bill Clinton, the fraudster posed with his wife Amarilis Osorio — who was sporting a large diamond ring on her finger. But there was no such ring listed on the couple's bankruptcy schedules.

“First the Osorios claimed it was cubic zirconia, then that (Amarilis) borrowed it from a friend in Venezuela,” Budwick said. “Through investigative work we found out the ring was real, who sold it to the Osorios, and that the Osorios paid $50,000.”

Mrs. Osorio's family then repaid that money to Budwick's client.

Claudio Osorio (left) with former U.S. President Bill Clinton (center) and Osorio's wife Amarilis Osorio (right). Courtesy photo.

Claudio Osorio (left) with former U.S. President Bill Clinton (center) and Osorio's wife Amarilis Osorio (right). Courtesy photo.In Budwick's experience, there's usually one main figurehead calling the shots in a Ponzi scheme, and they're quite the character.

“Their skill set is not in running the particular business,” Budwick said. “Their skill set is that they know how to manipulate people. They can be very charming, but they can also at times show their disappointment.”

In a videotaped deposition, Budwick asked Osorio a question he didn't like.

“I asked (Osorio) whether or not he had committed certain crimes,” Budwick said. “Then he adjusted his glasses.”

Budwick didn't realize until much later, when the case was featured on the TV show ”American Greed,” that he'd used his middle finger to make the adjustment.

“As I was watching the video deposition I realized,” Budwick said. “He just gave me the middle finger on national television.”

Lawyer, meet con man

Working a Ponzi scheme case means sitting down with the perpetrator at some point. For Budwick to do that effectively, he has to concoct a master plan of his own.

“It's always a challenge,” Budwick said. “Sometimes they may have their own personal agenda, and you need to recognize if that's the case. But it's important to meet with them, to be prepared for that meeting, and to understand when they're giving you accurate information and when they're not.”

Thomas Joseph Petters' mug shot.

Thomas Joseph Petters' mug shot.According to Budwick, accomplices are often remorseful and cooperative, and sometimes victims themselves. But it's important to weigh the value of the information they share against other witnesses and documents to know if they're trying to lead you astray.

When it was first uncovered in 2008, Petters' $3.65 billion Ponzi scheme was the biggest scam the U.S. had ever seen. Shortly after, Bernie Madoff and Allen Stanford took the top two spots.

Budwick's team represents the trustee for two Florida hedge funds that lost $651 million to Petters' fraud — a third of losses in the whole case, which originates in Minnesota. Budwick's investigation has been massive, leading him and his team all over the country to meet with victims and perpetrators.

“I've been to too many prisons to count,” Budwick said.

'Creditor cannibalism'

Budwick brought 150 lawsuits on behalf of client Palm Beach Funds, so it was crucial to carefully choose which were worth the fight.

“You can't litigate all these cases to trial within a Ponzi scheme case,” he said. “You need to try and resolve as many as you can, be as efficient as possible and only go to trial on the ones that make sense to go to trial, because you otherwise couldn't settle.”

Budwick has avoided fights by offering all defendants in the same position the same settlement terms, settling all but two cases.

“You want to avoid what I would call creditor cannibalism, which is creditors sort of attacking one another and not working together for the greater good,” Budwick said. “The creditors need to recognize at the end of the day that they're all crime victims and they should be working together to benefit all the victims of the crime.”

One of the two remaining cases is against financial services company GE Capital, accused of joining Petters' Ponzi scheme once it discovered what was going on.

Petters is serving a 50-year prison sentence at Leavenworth prison, and Budwick hopes to take GE Capital to trial this year.

The case is the culmination of Budwick's career, but in the eyes of fraud victims every case is just as huge.

“It's easy to lose focus because the attention tends to be on the billion-dollar Ponzi scheme cases, but there are hundreds that are less than that that just wipe out families,” Budwick said.

Budwick's grandparents suffered their own tragedy when they fled the Holocaust in the 1940s, swapping Poland for Cuba — until Fidel Castro came to power. They ran again, this time to New York.

And there, years later, Budwick became the envy of his friends.

“My father worked for Topps in New York, which is the maker of baseball cards, so I had the biggest collection in my neighborhood,” Budwick said.

Budwick was raised in Staten Island— a working class area with sanitation workers, school teachers, firemen and police officers abound. In fact, Budwick couldn't point to one lawyer he'd met growing up.

Dovid Budwick with his attorney father Michael Budwick, who manages his Little League Baseball team. Courtesy photo.

Dovid Budwick with his attorney father Michael Budwick, who manages his Little League Baseball team. Courtesy photo.But no matter — the profession found him during high school, when Budwick's family moved to Miami and he wound up in a county-wide mock trial competition. Before Budwick knew it, he was suing a party thrower, arguing for an imaginary plaintiff struck down by an underage drunk driver.

“These were things that I'd never even thought about,” Budwick said. “How to try a case, how to argue in front of a jury, how to cross-examine a witness.”

His team won second place, sparking an interest in Budwick that's never fizzled.

When he isn't scoring home runs in fraud cases, Budwick is managing his son's Little League Baseball team, or going to a local synagogue with his wife of 16 years and their three kids. The pair met thanks to a colleague in bankruptcy law who set them up on a blind date.

“Once in a while,” Budwick said, “It works.”

Michael S. Budwick

Born: September 1966, Brooklyn, New York

Spouse: Sharon Budwick

Children: Dovid, Shira, Shoshana

Education: University of Florida, J.D., 1992; B.S., B.A., 1988

Experience: Shareholder, Meland Russin & Budwick, 2002-present; Principal, Michael S. Budwick, 2000-2002; Associate, Kozyak Tropin & Throckmorton; 1992-2000; Management associate, Barnett Bank of South Florida, 1988.

More profile stories:

Legal Aid Superhero Barbara Prager on Hanging up Her Cape

How a Teenage Scrape With Cops Galvanized Jayne Weintraub's Career as Criminal Defense Lawyer

No Dodgy Deals: Meet Jose Arrojo, Miami-Dade's New Ethics Commission Director

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Growing Referral Network, Alternative Fees Have This Ex-Big Law’s Atty’s Bankruptcy Practice Soaring

5 minute read

Against the Odds: Voters Elect Woody Clermont to the Broward Judicial Bench

4 minute read

Miami Civil Judge Myriam Lehr to Say Goodbye to the County Court Bench

4 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250