Where Are They Now? Florida Lawyers Featured in Netflix's Ted Bundy Documentary

ALM's Daily Business Review caught up with prosecutors Larry D. Simpson and George R. "Bob" Dekle, and public defender Michael Minerva—three of the Florida attorneys featured in the Netflix original docuseries "Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes."

January 29, 2019 at 11:34 AM

6 minute read

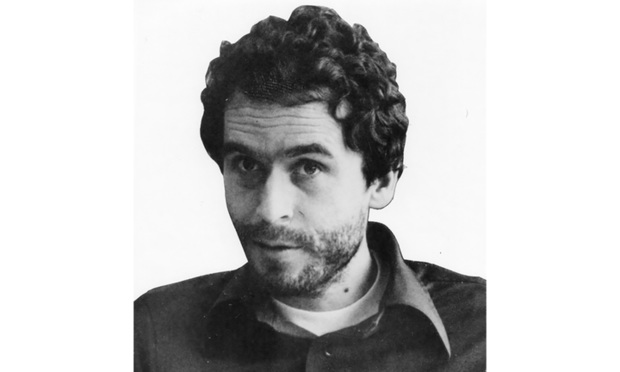

Ted Bundy. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Ted Bundy. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

On Thursday, 30 years to the day serial killer Theodore “Ted” Bundy met his end in a Florida State Prison electric chair, Netflix released a docuseries that's revived interest in a case that both horrified and bewitched 1970s America.

“Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes” revisits the former law student's crimes through numerous hours of taped interviews as he sat on death row. Bundy wasn't tried for the majority of the killings to which he was linked — more than 30 — but stood trial in Miami in June 1979 for the murders of two Florida State University students.

For the Florida lawyers assigned to prosecute and defend Bundy, his case presented a crucial learning curve.

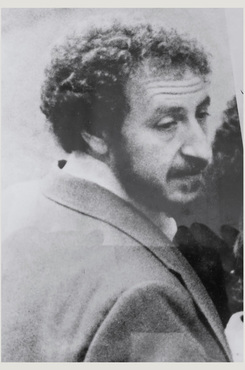

Prosecutor Larry D. Simpson. Courtesy photo.

Prosecutor Larry D. Simpson. Courtesy photo.It was a ”once-in-a-lifetime case” for Larry D. Simpson, a former prosecutor for the state attorney's office in Tallahassee.

“I just happened to be in the right place at the right time,” said Simpson, who was just 29 when he got the assignment — four years out of law school.

Bite marks, semen, hair and fiber samples sent Simpson down a scientific rabbit hole from which he's never fully emerged.

“The Bundy case was really a deep dive into forensic science,” Simpson said. “Once you have your eyes open to that type of evidence, it's extremely powerful in the court, and I really enjoyed working with it, learning about it and explaining it to a jury.”

Soon after, Simpson transitioned to private practice, where he stayed with partner Jimmy Judkins for more than 35 years, splitting time between criminal and civil cases. He often represented agricultural companies in products liability cases, the outcome of which hinged on scientific evidence.

Simpson is semi-retired, having decided two years ago, “I'd probably practiced about as much as I wanted to.” If he's not working on cases from home, Simpson is traveling to Pittsburgh and Atlanta to see his grandchildren, or sightseeing across the U.S. with his wife.

'A case that doesn't go away'

Michael Minerva, former Tallahassee public defender. Courtesy photo.

Michael Minerva, former Tallahassee public defender. Courtesy photo.Michael Minerva, then-Tallahassee public defender, represented Bundy when he faced murder charges in Miami and never expected the case to have a 40-year shelf life.

“I had no idea. Right after the trial and the execution, there was a flurry of books and then it was kind of dormant for a long time. Now it's like it happened yesterday,” Minerva said. “It's a case that doesn't go away.”

That said, it was Minerva's first televised case — an intimidating prospect, not unlike competitive sports.

“It's like all this tension that you get before the game begins, but then once it starts you're absorbed in doing it and you don't really think about the tension and the anxiety you felt beforehand,” Minerva said.

Bundy fired Minerva before he could finalize a deal that would have allowed the killer to swap execution for 75 years in prison.

Minerva lost his re-election bid after representing Bundy, then served as general counsel for the department of corrections and later became head of Capital Collateral Regional Counsel, working on post-conviction cases for death row inmates. As an appellate lawyer, he worked on the Florida Supreme Court case Allen v. Butterworth, which overturned the Death Penalty Reform Act of 2000 that restricted the rights of death row inmates litigating their cases.

Minerva then ended his career as an assistant, back at the public defender's office. He retired in 2001 but was soon recruited by the Innocence Project of Florida, advising staff on litigation. He retired — for good — in 2013, and has remained in a small town near Jacksonville, catching up on everything he never had time to read.

Related story: Sentencing Judge Said Serial Killer Ted Bundy Would Have Made a Great Lawyer, Tapes Reveal

The 'Prettiest' Serial Killer

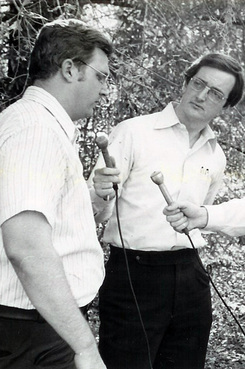

George R. “Bob” Dekle, former assistant state attorney in Tallahassee, 1978. Courtesy photo.

George R. “Bob” Dekle, former assistant state attorney in Tallahassee, 1978. Courtesy photo.George R. “Bob” Dekle, former assistant state attorney in Tallahassee, has been featured on four Bundy documentaries and said he too is amazed there's still such interest in the case.

“There has been so much crime and so many horrible people that have done such terrible things since then that it seems like [Bundy] would be forgotten by now,” Dekle said. “He's probably the prettiest and most articulate of the serial killers, and that may be why his story's got staying power.”

Dekle prosecuted Bundy in a third criminal trial over the murder of Kimberly Leach and later witnessed his execution.

“As the electricity coursed through his body you see his fist tighten. … And I remember thinking at the time, I wonder how many throats that fist has tightened around,” Dekle said in the Netflix docuseries.

George R. “Bob” Dekle being interviewed by reporters at the scene where Kim Leach's body was found. Photo: Lake City Reporter.

George R. “Bob” Dekle being interviewed by reporters at the scene where Kim Leach's body was found. Photo: Lake City Reporter.For Dekle, Bundy's case was a crash course in lawyering and forensic science. After all, the only section of the crime lab that wasn't involved in the case was firearms.

“I learned more about how to be a lawyer in the two years that I spent preparing and trying this case than I did in the three years I spent in law school and the five years I had spent practicing law,” Dekle said.

According to Dekle, the cases that came after Bundy impacted him most profoundly, because prosecuting crime in a small town meant most victims were people he knew.

One case involved his wife's co-worker, murdered after walking in on daytime burglars. Another concerned the kidnap and murder of an agricultural inspector Dekle knew well. For that death, Dekle prosecuted a drug-smuggling ring made up of Chicago police officers.

“Whenever you're doing something like that it really tears you up,” he said.

Dekle stayed in his post until 2005 when he left to pursue his dream job — teaching law students how to prosecute cases at the University of Florida. He's also written several books, including a law textbook and a memoir on the Bundy case. His next book, slated for May, is about morphine murderer Carlyle Harris, who Dekle described as “a gilded-age Ted Bundy.”

More criminal law stories:

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

US Judge Cannon Blocks DOJ From Releasing Final Report in Trump Documents Probe

3 minute read

SCOTUSblog Co-Founder Tom Goldstein Misused Law Firm Funds, According to Federal Indictment

2 minute read

Automaker Pleads Guilty and Agrees to $1.6 Billion in Payouts

Read the Document: DOJ Releases Ex-Special Counsel's Report Explaining Trump Prosecutions

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Decision of the Day: Judge Dismisses Defamation Suit by New York Philharmonic Oboist Accused of Sexual Misconduct

- 2California Court Denies Apple's Motion to Strike Allegations in Gender Bias Class Action

- 3US DOJ Threatens to Prosecute Local Officials Who Don't Aid Immigration Enforcement

- 4Kirkland Is Entering a New Market. Will Its Rates Get a Warm Welcome?

- 5African Law Firm Investigated Over ‘AI-Generated’ Case References

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250