Amid Crisis, Cuba Plans Revamp of State and Legal System

Nearly a year of debate and discussion ended last month with the approval of Cuba's first constitutional reform since 1976.

March 14, 2019 at 11:14 AM

5 minute read

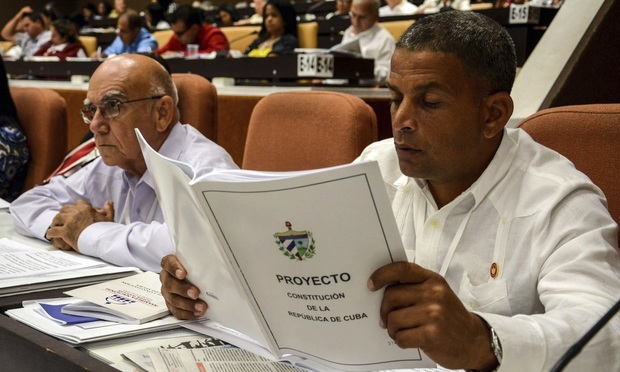

In this July 21, 2018, photo, a member of the National Assembly studies the proposed constitutional update in Havana, Cuba. (Abel Padron, Agencia Cubana de Noticias via AP, File)

In this July 21, 2018, photo, a member of the National Assembly studies the proposed constitutional update in Havana, Cuba. (Abel Padron, Agencia Cubana de Noticias via AP, File)

In the midst of a regional crisis over Venezuela and tough economic straits, the Cuban government is about to launch a sweeping makeover of its centrally planned, single-party system with dozens of new laws that could reshape everything from criminal justice to the market economy.

Nearly a year of debate and discussion ended last month with the approval of Cuba's first constitutional reform since 1976. Some observers see the new constitution as merely a cosmetic update aimed at assuring one of the world's last communist systems won't get another revamp until long after the passing of its founding fathers, now in their late 80s and early 90s. Others see the potential for a slow-moving but deep set of changes that will speed the modernization of Cuba's economically stagnant authoritarian bureaucracy.

Cuban legal experts told The Associated Press that they expect the government to send the National Assembly between 60 and 80 new laws over the next two years to replace ones rendered obsolete by the new constitution. The assembly is virtually certain to unanimously approve all government proposals, as it has for decades.

“I expect to see big changes in Cuba with the new constitution,” said Julio Antonio Fernandez, a constitutional law professor at the University of Havana. “A new state structure, a transformed political system, led by the Communist Party, of course, but different and confronting big challenges.”

One of the first changes will be in Cuba's political system. Within five months, the government is required to pass a new electoral law that splits the roles of head of state and government between the current president and the new post of prime minister. A new set of governors will replace the Communist Party first secretaries as the highest official in Cuba's 15 provinces.

While the Communist Party remains the only permitted political group, the wording of the new constitution could allow voters to choose between various candidates rather than simply voting yes or no for a candidate preselected by a government commission, experts said.

A new business law could create a formal role for small- and medium-sized businesses. Until now, all private workers and employers are legally classified as “self-employed,” leading to situations in which hundreds of thousands of “self-employed” waiters, cooks, maids, construction workers and janitors go to work each day for the “self-employed” owners of restaurants, bed-and-breakfasts and construction contractors.

Business owners hope legal recognition will bring them privileges such as the right to import and export, now held only by state monopolies.

“There's a full-on effort to give life to the new constitution, to accompany it with laws so it doesn't become a dead letter,” Homero Acosta, the secretary of Cuba's Council of State and one of the key figures in the reform, said on state television this month.

A new family code is expected to address the issue of gay marriage, which was struck from the new constitution after popular resistance.

A new criminal code will for the first time create the right of habeas corpus, requiring the state to justify a citizens' detention, and give Cubans the right to know what information the government holds about them.

The revamped criminal law could also, experts said, contain stronger provisions against domestic violence, greater environmental protections and animal rights and create tougher punishments for government mismanagement and corruption.

Cuba's powerful military and intelligence ministries employ tens of thousands of agents and informants, control much of the economy and are often exempted from the rules governing civilian sectors of the government. Whether the Interior Ministry and Revolutionary Armed Forces will be subject to the new limits in the legal reform remains an open question.

Cuba is in its fourth year of expected zero to minimal growth, and the government feels increasingly threatened by the Trump administration's effort to overthrow Venezuela's Cuban-allied government as the first step in an offensive against socialist states throughout Latin America.

Only 78 percent of registered voters, some 6.8 million out of 8.7 million, said “yes” to the new constitution in a Feb. 24 referendum. That's a massive approval rate in any other country but relatively low for Cuba, where voters usually approve government proposals by margins well over 90 percent.

In this case, some 700,000 voted “no,” while others abstained or filed marred or blank ballots.

That could put unusual pressure on the government to come up with new laws that win widespread public approval, rather than simply imposing new regulations after closed meetings of Communist Party and government leaders.

“The referendum showed that Cuba is a more politically diverse society than it often seems on the surface,” constitutional lawyer Raudiel Pena said. “Now let's hope that lawmakers really take that into consideration.”

Andrea Rodriguez reports for the Associated Press. Associated Press writer Michael Weissenstein contributed to this report.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Winston & Strawn Snags Sidley Austin Cross-Border Transactions Partner in Miami

2 minute read

Miami’s Arbitration Week Aims To Cement City’s Status as Dispute Destination

3 minute read

Brazil Is Quickly Becoming a Vital LatAm Market for Greenberg Traurig, Other US Law Firms

5 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250