Senate Tees Up School Safety Bill, 'Guardian' Debate

The Senate Appropriations Committee approved a rewrite of the proposal to give more flexibility to school districts that want to participate in the controversial guardian program.

April 15, 2019 at 12:43 PM

5 minute read

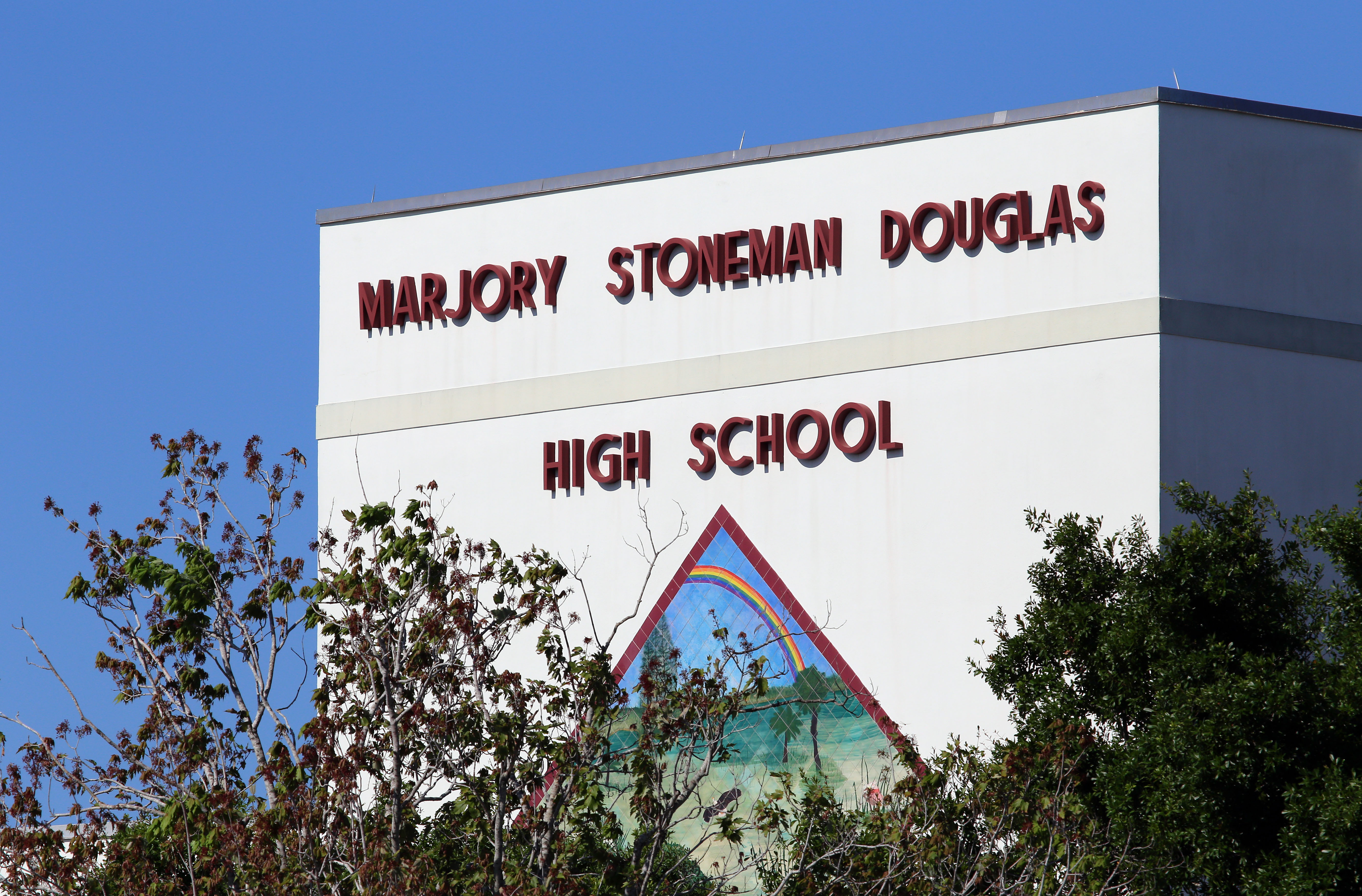

The Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida on April 25, 2018. Courtesy photo.

The Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida on April 25, 2018. Courtesy photo.

Nearly 14 months after the Parkland school shooting, state senators moved toward passing a wide-ranging school safety bill that would include allowing classroom teachers to serve as armed school “guardians.”

The Senate Appropriations Committee approved a rewrite of the proposal to give more flexibility to school districts that want to participate in the controversial guardian program. Other changes Thursday included an expansion of mental-health services in schools that would assist students with suicidal intentions, trauma and violence.

The proposal (SB 7030) is now ready to go to the full Senate as the annual legislative session enters its final three weeks. While Republican leaders are supporting the measure, passage is not expected to happen on a party-line vote.

Sen. Anitere Flores, R-Miami, sided Thursday with Democrats in voting against the bill because of the provision that would allow armed teachers. Meanwhile, Sen. Bill Montford, D-Tallahassee, said he could not support the provision but said “maybe I can get there.”

“More good comes from this [bill] than bad, but I firmly believe that kids' lives should be protected more than just by hope, and for that reason I can't vote for this bill today,” Flores said.

Her GOP colleagues, however, argued the expansion of the guardian program is needed to ensure that schools would have armed people immediately available to thwart threats in active-shooter cases.

Lawmakers last year rushed to pass a school-safety bill after confessed gunman Nikolas Cruz killed 17 students and faculty members at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland on Valentine's Day. The bill addressed numerous issues, including creating the guardian program to allow armed school personnel whose primary duties are outside the classroom.

Many school districts have declined to go along with creating guardian programs. But the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission, which was created in last year's bill, issued numerous recommendations in January, including expanding the guardian program to allow armed teachers.

Senate and House Republican leaders have followed that recommendation.

“It would be my greatest hope in life that we can live in a world where there were no guns in classrooms,” Senate Appropriations Chairman Rob Bradley, R-Fleming Island, said. “But Nikolas Cruz shattered that hope when he brought a gun into a classroom and killed our precious children. And that's the reality we live in today. Period.”

One of the ways senators are looking to expand the guardian program would be to allow school districts that want to participate to contract with out-of-county sheriff's offices to train guardians. That would give flexibility to school districts that don't see eye to eye with their counties' sheriff's offices about participation in the program.

In the last year, 25 school districts have implemented some type of the guardian program, said the sponsor of the bill, Senate Education Chairman Manny Diaz Jr. He added that 12 other school districts are looking into doing so.

“We have 67 districts that all have different needs,” Diaz, R-Hialeah, said. “The flexibility and the local option is really the theme of the bill.”

During a four-hour hearing Thursday on the proposal, a number of teachers opposed allowing teachers to volunteer to be guardians.

“Classroom teachers are already surrogate parents, we are guidance counselors. We are schedulers. I help kids get through college applications. That's the stuff I want to do,” said Ellen Barber, a Palm Beach County high school teacher. “I don't want to carry a gun, and I don't want my colleagues to carry a gun.”

Under the bill, guardians would get a $500 stipend for participating in the program, which would require them to go through psychological evaluations and 144 hours of training. Each guardian would need to be appointed by a school superintendent or charter school principal.

Democrats overwhelmingly opposed the guardian provision, arguing that more guns in schools will not make students safer and could lead to scenarios where gun-related accidents can happen.

Yet, Democrats said they like other provisions in the bill that would expand mental-health services for students, enhance communications between schools about new students' histories with behavioral issues and improve data collection on incidents that occur on school premises.

“If we really want to get to the root cause of the problem, not just in schools, but in society too, we need to address mental health,” Montford said.

One of the changes to the bill would require school districts to enhance mental-health services provided to students.

Sen. Kathleen Passidomo, R-Naples, proposed an amendment that would require school districts to offer mental health care to students, including programs that assist students in dealing with anxiety, depression, bullying, trauma and violence as well as suicidal tendencies.

Mental health services have become a focal point during debate following two recent suicides of Parkland students who had survived the mass shooting last year. The suicides happened within a one-week span.

“The bottom line is, what is more important than protecting our children and making sure they are safe, both physically and mentally?” said Passidomo, whose amendment was approved.

To cover the cost of mental-health services, the Senate has proposed in its 2019-20 budget setting aside $100 million, a 44 percent increase from the current year. The House is pitching $30 million less than the Senate.

The House version of the school safety bill is also ready for a full floor vote.

Ana Ceballos reports for the News Service of Florida.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Second DCA Greenlights USF Class Certification on COVID-19 College Tuition Refunds

3 minute read

How Uncertainty in College Athletics Compensation Could Drive Lawsuits in 2025

St. Thomas University Settles With Fired Professor Who Had Alleged Academic Freedom Violations and Discrimination

9 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250