Florida Judge Warns Against Using Case Law, Not Statutes, to Support Hearsay Exceptions

Fourth District Court of Appeal Judge Robert M. Gross wrote that he often sees arguments that overlook Florida Statutes governing hearsay in favor of focusing on broader case-law analysis.

July 25, 2019 at 02:43 PM

5 minute read

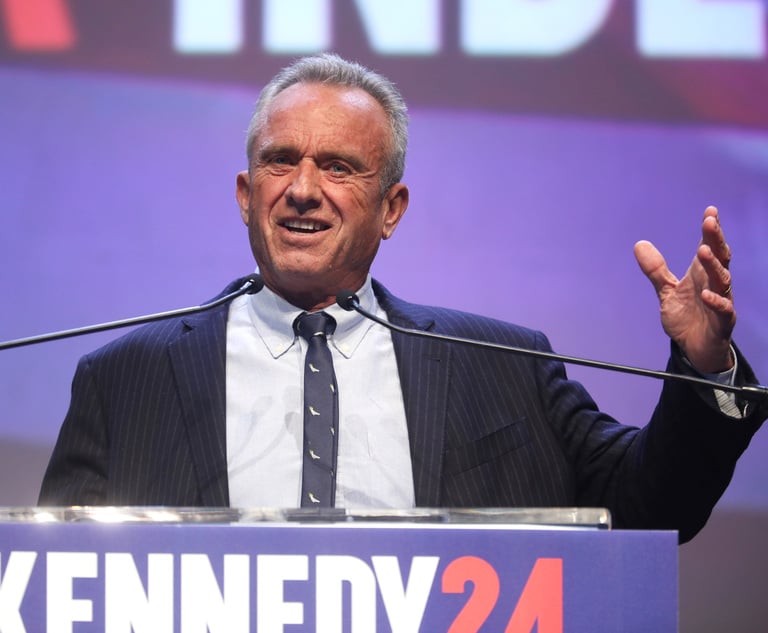

Fourth District Court of Appeal Judge Robert Gross. Photo: Melanie Bell/ALM.

Fourth District Court of Appeal Judge Robert Gross. Photo: Melanie Bell/ALM.

Fourth District Court of Appeal Judge Robert M. Gross highlighted what he said was a recurring problem in criminal cases, thanks to confusion around hearsay and Confrontation-Clause analysis.

Gross wrote that he often sees broad considerations of case-by-case examples, when instead arguments and decisions should be based on the actual language in Florida Statutes 90.803, 90.804 and 90.805, which lay out the rules on hearsay exceptions.

The judge's comments came as the Fourth DCA gave a new trial to Sherard Adams, sentenced to life in prison after he was convicted of hiring a gunman to kill his ex-girlfriend in 2013. The appellate panel ruled Wednesday that some of the evidence used against Adams shouldn't have made it to trial because it didn't fit under the exceptions to hearsay explained in Florida statutes.

As a general rule when analyzing hearsay evidence in Florida, courts rely strictly on what's inside the statute, according to University of Miami professor of law Ricardo J. Bascuas, who specializes in evidence, criminal procedure and criminal law.

“[Judge Gross] is saying the law spells out when hearsay is reliable enough to be admitted, and what judges are supposed to do is read the law and see if the hearsay statement comes within those provisions—and that's it,” Bascuas said.

Gross also stressed that despite major similarities, the Confrontation Clause from Amendment Six of the U.S. Constitution—which gives defendants in criminal cases the right to face their accusers—and statutory language about hearsay aren't the same thing.

“They are similar, they involve similar concepts, but they're still two completely independent steps,” Bascuas said.

Because the Constitution gives criminal defendants the right to confront those making allegations against them, hearsay isn't allowed unless there's a statutory exception. Using language from the federal and Florida statutes interchangeably can confuse a legal argument, according to Gross.

“Such an approach would allow hearsay exceptions to swallow the rule against hearsay,” Gross wrote.

This issue crops up often, according to Kendall Coffey of Coffey Burlington, who teaches Florida constitutional law at the University of Miami. He said that's because the many exceptions to the hearsay rule mean case law can develop a life of its own.

“What [Gross] is advocating for is that this kind of hearsay should only be admitted if it meets the terms of the rule, and judges should not consider whether there is some broad reason to find the statement trustworthy and admissible if in fact it violates the hearsay rules,” Coffey said.

The evidence

Adams pleaded not guilty at trial, where he came up against statements from his co-defendant, who voluntarily confessed to a friend about shooting the victim—not knowing the friend had become a police informant.

The co-defendant initially confessed to police, but later recanted and refused to testify at trial. The state argued that happened because Adams had sent a letter to the co-defendant, threatening his girlfriend and family if he testified.

The co-defendants' statements still made it to trial, but they shouldn't have, according to the Fourth DCA. Adams' Fort Lauderdale attorney Arthur E. Marchetta Jr. had argued their admission violated his client's rights because he didn't have the chance to confront the co-defendant and fairly test his credibility.

The Fourth DCA also ruled that a taped phone call from Adams to the victim's father shouldn't have been admitted, as it proved nothing more than the father's opinion. It was one of many calls in which Adams asked what happened to the victim, while the father accused the defendant of murder and called him ”a liar, a punk and a junkie,” according to Wednesday's ruling.

Defense counsel Marchetta was pleased with the decision.

“My client and I feel the Fourth [DCA] made the appropriate decision under the facts of this case, and we are looking forward to retrying the case with the scales not tipped in favor of the state,” Marchetta said.

The Fourth DCA ruled the trial court was right to admit the letter, and the opinion noted that it's possible the defendant had forfeited his hearsay objection by writing it. But since the trial court didn't have the opportunity to rule on that argument from the state, it remains to be seen.

How will the new Florida Supreme Court rule?

One of the cases cited in the Fourth DCA's opinion, Moscatiello v. State, is pending before the Florida Supreme Court, as are others involving similar issues. That means things could get interesting, as Coffey sees if, because there are three new justices on the bench.

“In times past, Florida's Supreme Court has, in significant respects, been more sensitive to the rights of the accused than the U.S. Supreme Court, because we have our own state Constitution,” Coffey said. “The Supreme Court of Florida has its own traditions with respect to the rights of the accused, and the new Supreme Court will be closely watched to see if it maintains those traditions or rolls back some of the rights of the accused.”

Fourth DCA Judge Melanie G. May wrote the opinion, with Judges Dorian K. Damoorgian and Robert M. Gross concurring.

Florida Attorney General Ashley Moody and Assistant AG Mark J. Hamel represent the state. Their office declined to comment on the case.

Read the court opinion:

More appellate court stories:

Neglect? Yes. Excusable? No. Florida Court Reinstates Ruling Over Defendant No-Show

'Dear Florida Supreme Court: We Need Your Help,' 11th Circuit Writes in SOS About Damages

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Holland & Knight Hires Former Davis Wright Tremaine Managing Partner in Seattle

3 minute read

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute read

Plaintiffs Attorneys Awarded $113K on $1 Judgment in Noise Ordinance Dispute

4 minute read

Local Boutique Expands Significantly, Hiring Litigator Who Won $63M Verdict Against City of Miami Commissioner

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 15th Circuit Considers Challenge to Louisiana's Ten Commandments Law

- 2Crocs Accused of Padding Revenue With Channel-Stuffing HEYDUDE Shoes

- 3E-discovery Practitioners Are Racing to Adapt to Social Media’s Evolving Landscape

- 4The Law Firm Disrupted: For Office Policies, Big Law Has Its Ear to the Market, Not to Trump

- 5FTC Finalizes Child Online Privacy Rule Updates, But Ferguson Eyes Further Changes

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250