'I'm Not Going to Hide Who I am': Attorney John 'Jack' Lord Jr. Champions LGBTQ Rights

When John "Jack" Lord Jr. joined Foley & Lardner almost 25 years ago, marriage equality benefits didn't exist for employees. Because, well, neither…

August 09, 2019 at 02:48 PM

7 minute read

John “Jack” Lord Jr, partner at Foley & Lardner in Miami. Courtesy photo.

John “Jack” Lord Jr, partner at Foley & Lardner in Miami. Courtesy photo.

When John “Jack” Lord Jr. joined Foley & Lardner almost 25 years ago, marriage equality benefits didn’t exist for employees. Because, well, neither did marriage equality.

The first time Lord told a client he was gay, it was because she had noticed he was wearing a wedding ring his domestic partner had given him.

“She was like, ‘Oh, you got married.’ And I said ‘No, my partner gave that to me.’ She somehow didn’t know I was gay, and I just remember, it wasn’t like an, ‘Oh my God, that’s horrible’ kind of reaction, but it was a very surprised, shocked reaction,” Lord said. “You don’t see that now, and that’s so nice, actually.”

For Lord, co-chair of Foley’s national labor and employment practice group and co-chair of its lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender affinity group, being open about his sexual orientation has always been a no-brainer.

“I personally have always been out at work, and I think it’s important,” Lord said. “Obviously, there are going to be people that, unfortunately, are going to make bad decisions because that’s on your website. But overall, I’m not going to hide who I am, and also I think it is a way to boost your career.”

Foley’s LGBTQ group has more than 200 members and allies who act as a national social support system aimed at nurturing the careers of younger attorneys and creating mentors out of older ones.

Public attitudes toward gay, lesbian and queer people have transformed in the past 25 years, in Lord’s view. But he says transgender people also haven’t yet enjoyed the same treatment, despite having the right to be free of discrimination and having certain legal protections.

That’s why Lord handles pro bono cases for transgender people, many of whom are children that have been blocked by their school from using a particular bathroom or changing area after they’ve transitioned. In one of the firm’s cases, a transgender child in California died by suicide after a hospital refused to refer to the child appropriately with the proper gender pronouns.

Lord’s firm also handles pro bono cases for LGBTQ senior citizens who allege nursing home staffers abuse or harass them because of their sexual orientation.

His pro bono work overlaps with his other practice areas, which involve training, counseling and defending employers, in fields like health care and education, against breach of contract and discrimination claims.

If, for example, a client hires a man who, six months later starts presenting as a woman and asking to be called by a different name, Lord educates and advises that company about what it should and shouldn’t do.

“I don’t fault people for not knowing,” he said. “I do want them to be curious, and I want them to be open minded.”

Lord’s clients include the Mayo Clinic, a nationwide nonprofit organization with about 63,000 employees. And he practices what he preaches, having encouraged his own firm to implement domestic-partner benefits for staff.

Lord studied Spanish and almost became a professor of languages before pivoting to law school, where he was drawn to employment law as an area where complex and ever-evolving case law collides with unique, emotionally charged situations.

“Most companies have employees, and employees tend to create legal problems,” Lord said. “So there’s lots and lots of this work, which means there’s a lot of creative lawyers out there always looking at the law and coming up with new ways to change it.”

When Lord graduated in 1994, it was the perfect timing, in his view, since laws around the Civil Rights Act of 1964 went through a major upheaval. For the first time, plaintiffs alleging discrimination could receive a jury trial and request both punitive and pain-and-suffering damages.

“The jury trial was a big deal because before that you had to go in front of a judge, and juries tend to give bigger awards than judges,” he said.

Lord’s job has since evolved to exist outside the courtroom as much as possible, but it used to revolve around it. The ’90s was a new frontier for employment law as the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Family and Medical Leave Act were also in their infancy. That meant employers suddenly had much more to worry about, according to Lord, who cut his teeth defending dozens of cases alleging age, race and gender discrimination in the’ 90s.

“Nobody really knew how to value these cases,” Lord said. “So the employee was asking for a lot of money if we were gong to settle, and the employer only wanted to pay a very small amount, so things tended to go to trial more.”

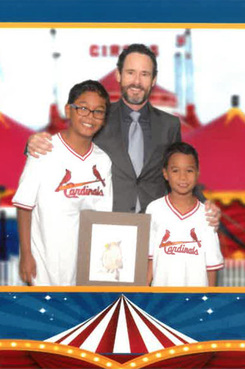

Jack Lord celebrating Adoption Day with children of the guardian ad litem program. Courtesy photo.

Jack Lord celebrating Adoption Day with children of the guardian ad litem program. Courtesy photo.Lord has also served on a handful of nonprofit boards, and is a pro bono guardian ad litem for children with the Department of Children and Families, many of whom have been abused or neglected by their parents. His job is to talk to figure out what’s going on and tell the court what’s in the child’s best interest.

What’s hardest for Lord is realizing that some parents can’t look after their children—because these adults have committed serious physical abuse, or even because they’re not intellectual capable of looking after them. If the parents disagree, the case goes to trial.

“The parents are not happy with me. They’re furious. They have lawyers,” Lord said. “But if I truly think it’s in the best interest of the child not to be in that home anymore, then that’s what I have to report back to the court.”

Lord’s ability to wear numerous professional hats at once is something he says comes from his parents, who were both leaders in their fields. Lord’s father was president of Bank of America in Orlando and sat on charitable trusts for nonprofit organizations, while his mother was a registered nurse, ran her own rehab business and volunteered for non-profits and aid services.

“They showed me the importance of it,” Lord said. “It’s rewarding to be a leader, but it’s also important to do it in the right way.”

But that can get pretty stressful, according to Lord.

“Because I could potentially go insane, I do yoga almost every day,” Lord said.

Lord practices Ashtanga yoga, learning and memorizing a string of postures that gradually increase in difficulty.

But despite the stresses of his profession, it’s worth it for Lord just to hear how Foley & Lardner’s LGBTQ work helps his peers.

He said, “To have people appreciate within the firm—both that we’re doing things to make sure our community is recognized, and that people do know we deserve and demand respect, and also that we are doing things for the outside world—is really rewarding.”

John “Jack” Lord Jr.

Born: September 1969, Orlando, Florida

Education: Duke University School of Law, J.D., 1994; University of Florida, B.S., 1990

Experience: Partner, Foley & Lardner, 1994–present

More attorney profiles:

You’ve Been Served: How Marko Cerenko Went From Tennis Champ to High-Stakes Miami Litigator

How Miami Attorney Curtis Osceola’s ‘Crazy Plan’ Made Him the Miccosukee Tribe’s First Lawyer

After the Massacre: Fired by Nixon, Miami Lawyer Jon Sale Rose to Prominence

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Carol-Lisa Phillips to Rise to Broward Chief Judge as Jack Tuter Weighs Next Move

4 minute read

Growing Referral Network, Alternative Fees Have This Ex-Big Law’s Atty’s Bankruptcy Practice Soaring

5 minute read

Against the Odds: Voters Elect Woody Clermont to the Broward Judicial Bench

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Thursday Newspaper

- 2Public Notices/Calendars

- 3Judicial Ethics Opinion 24-117

- 4Rejuvenation of a Sharp Employer Non-Compete Tool: Delaware Supreme Court Reinvigorates the Employee Choice Doctrine

- 5Mastering Litigation in New York’s Commercial Division Part V, Leave It to the Experts: Expert Discovery in the New York Commercial Division

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250