On Dec. 10, 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 8-1 that the one-year filing deadline for Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA) lawsuits is determined from when the alleged violation occurs, not when it is discovered. The case was an appeal of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit’s ruling in Rotkiske v. Klemm, 890 F.3d 422 (3d Cir. 2018), where the court found that the statute of limitations starts to run when the defendant violates the FDCPA. This resolution will greatly benefit creditors and those collecting debts for the creditors.

In 2008, a debt collector sued Kevin Rotkiske due to defaulted credit card debt and attempted to serve him at a prior address. At such address, an individual unknown to Rotkiske accepted service on his behalf. As a result, the debt collector eventually withdrew its lawsuit after it was incapable of locating Rotkiske personally.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law are third party online distributors of the broad collection of current and archived versions of ALM's legal news publications. LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law customers are able to access and use ALM's content, including content from the National Law Journal, The American Lawyer, Legaltech News, The New York Law Journal, and Corporate Counsel, as well as other sources of legal information.

For questions call 1-877-256-2472 or contact us at [email protected]

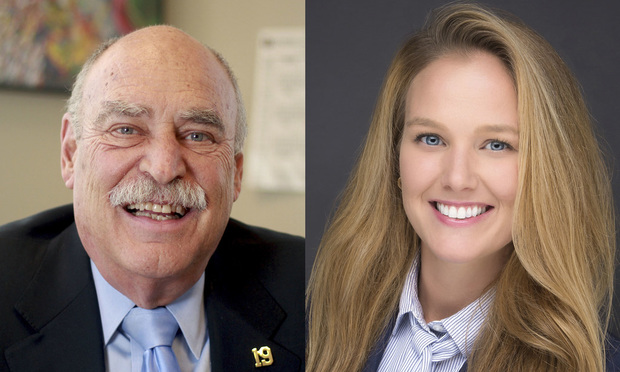

Charles Tatlebaum, left, and Brittany Hynes, right.

Charles Tatlebaum, left, and Brittany Hynes, right.