'Most Troublesome' Issue: Experiment Tests Remote Jury Trial With COVID-19 Around

Broward Chief Circuit Judge Jack Tuter is running an experiment intended to create a template for remote jury trials and maybe even a return to courthouse jury trials. With COVID-19, the challenges are daunting.

May 14, 2020 at 07:06 PM

7 minute read

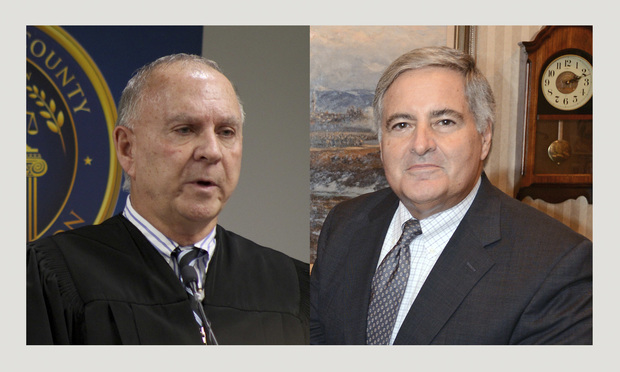

Judge Jack Tuter, left, and Jack Scarola, right.

Judge Jack Tuter, left, and Jack Scarola, right.

America is reopening again in the coronavirus era, but the jury trial calendar remains a blank slate.

Broward Chief Circuit Judge Jack Tuter is leading the jury charge (pun intended), but it's no easy thing. As he steps into the frontier during a health care pandemic, he has a rapt national audience.

"This jury trial issue is the most troublesome of the ones we're dealing with right now," Tuter said in a telephone interview as the Fort Lauderdale area prepared to begin reopening Monday. "Everything depends on what happens in the real world of COVID."

Attorneys are working with him behind the scenes in Broward County to explore concepts like virtual jury trials and a return to in-person civil and criminal jury trials in the COVID-19 era. But the social-distancing logistics—starting with the morning jam at the entry's X-ray machines and extending to deliberation rooms—are breathtaking.

Tuter and attorneys with the American Board of Trial Advocates conducted a mock civil jury trial Monday with powerhouse plaintiffs attorney Jack Scarola serving as the jury foreperson to test the new reality.

Tuter and ABOTA are working with New York University's Civil Jury Project to create a template for other judges to follow if the coronavirus runs wild for two years as some predict and if remote jury trials get beyond the hypothetical stage.

"Judge Tuter has taken national leadership," Scarola said. "I think we are ahead of the curve to move to the experimental stage that we're in."

Plantation civil litigator Mitchell Chester, an ABOTA member who helped organize the remote trial, said, "I'm not aware of any lawyers and judges who have done this up until now anywhere in the country, and the people at NYU say southeast Florida is far ahead."

In an obviously condensed form, Tuter ran a 90-minute, start-to-finish trial on Zoom software focused on how to call witnesses and enter exhibits. The jury was mostly plaintiffs lawyers who heard a personal injury case involving a kid on a dirt bike who fell on unfenced property.

When it came to deliberations, Scarola of Searcy Denney in West Palm Beach said the mock jurors were working under a time limit in a Zoom video conference breakout room overseen by a court technical staffer. The jury was not shooting for a unanimous verdict. It was more a test of emailing a verdict form to the remote foreperson and getting it back to the judge.

"It is a first step in what I anticipate is going to be a pretty long journey, but one that we need to take," Scarola said. "It generally went well, but it demonstrated that there is significant additional work that needs to be done before we can start to conduct jury trials remotely."

The next stage of the virtual jury trial experiment will be organizing online voir dire with judicial assistants serving as prospective jurors in late May or early June. That's definitely more problematic.

The jury summons process went on hiatus in Florida when trials were suspended in March, and the office would have to be revived. A one-third response rate was all that could be expected before the pandemic, so it's reasonable to expect a lower rate for either an in-person or remote calls.

"One concern is that the people responding to summonses are going to be self-selecting in a manner that skews the jury pool," Scarola said, anticipating fewer older jurors and fewer people from the giant pool of 36 million newly unemployed Americans.

Chester worries about both the digital and technological divide for seating a representative jury. Seniors are the least likely to be sophisticated computer users, and many people of all ages have limited access to high-speed Wi-Fi connections.

Under the circumstances, Tuter could foresee a jury composed of "middle-class people with good internet access. That seems to be not very due-process-minded."

Scarola likes the idea of longer questionnaires for prospective jurors, but he isn't sold on the remote mechanics, which transfer physical observations to a small window showing only faces.

"To the degree that remote selection depends on a greater dependence on one-on-one, electronic-face-to-electronic-face communication, it changes the dynamics of the selection process in a way that right now I'm not comfortable with," Scarola said. "I want to be able to see that panel as a whole, and I want to be able to observe the reaction of other jurors to whom I am not specifically addressing a particular question."

More questions abound about criminal jury trials and in-person trials back in the shuttered courthouses, and Tuter is trying to answer those, too. For starters, both sides would have to agree to virtual trials, and stipulations might be needed to address the likelihood of unforeseen problems.

The jury room in the main Fort Lauderdale courthouse normally holds about 700 people. With social distancing, that drops to about 60, which isn't enough to seat a murder jury of 12 plus alternates. Elevators would be reduced to one person per ride, which means assembling even a small group could take 15 minutes.

The well of the court is normally populated with a judge, clerk, bailiff, two sets of attorneys using stationary microphones and possibly a court reporter. The jury would have to be dispersed in the spectator section, which raises another question of how to accommodate spectators.

For criminal cases, the Broward Sheriff's Office jail population has been reduced by about 800 to high-risk inmates and prisoners with immigration holds. The total number of detainees at its four facilities totaled 2,755 people on Monday, Tuter said.

"If I'm going to get criticized, it's because we were slow to open, not that we opened too soon," Tuter said. "We're not going to take the risk that a 60-year-old person or an 80-year-old person summoned to court is going to get sick."

Thousands of remote hearings have been held since courts closed, but jury trials are off the table by court order in Florida until at least July 6 with an option to extend. The Florida Supreme Court order also encourages thinking about the permanent adoption of remote proceedings.

Tuter expects to begin reopening courthouses, most likely starting with the clerk's office, in June. If he can work out remote voir dire issues, he guessed the first virtual trial could be scheduled in late September or early October, but he's uncertain whether a juror will step back into the courthouse before the end of the year.

"I think that we are going to be compelled to move into some type of remote procedure," Scarola said. "If the alternative is you're going to try your case remotely or you're not going to try it for at least the next six months, there will be some who will elect to try it remotely."

The attorneys agreed simple business disputes and personal injury cases with few documents are the most likely to elect remote jury trials.

"It may be that we don't call juries for several weeks or months depending on the medical situation at the time," Tuter said. "I just feel if we're ordering people for jury service, we have to be dadgum certain that they're not exposed."

Read more:

Chief Justice Canady Releases 'Best Practices' for Florida Courts Amid COVID-19

Florida State Courts Extend Coronavirus Outage Into July

For 'Safe Return,' Task Force to Guide Gradual Reopening of Florida Courts

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Plaintiffs Attorneys Awarded $113K on $1 Judgment in Noise Ordinance Dispute

4 minute read

US Judge Cannon Blocks DOJ From Releasing Final Report in Trump Documents Probe

3 minute read

Read the Document: DOJ Releases Ex-Special Counsel's Report Explaining Trump Prosecutions

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250