From Police Chief to VP? Inside Val Demings' Unlikely Path

As a Black woman with a background in policing who hails from America's premier battleground state, Val Demings has honed the charisma she learned in high school to build a rapid national profile.

July 28, 2020 at 08:08 AM

7 minute read

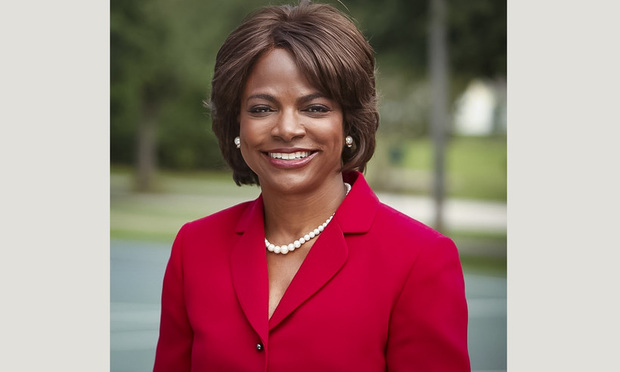

U.S. Rep. Val Demings, D-Fla.

U.S. Rep. Val Demings, D-Fla.

Val Demings has already been vice president.

In 1972, the future Florida congresswoman was a young Black girl struggling to make friends at a predominantly white Jacksonville high school. She and her best friend, Vera Hartley, created the Charisma Club. Hartley was president and Demings was her second-in-command.

"We created an environment of inclusion," Hartley said, recalling how she and Demings invited white students to join. Then "we were able to get into other clubs."

Nearly four decades later, Demings is again being considered for vice president — this time by presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden. As a Black woman with a background in policing who hails from America's premier battleground state, Demings has honed the charisma she learned in high school to build a rapid national profile.

But she's also facing scrutiny, particularly over her four years as Orlando's police chief. While those credentials could blunt President Donald Trump's argument that a Biden administration would lead to lawlessness, they could also spur unease among progressives who are leery of law enforcement, especially at a time of reckoning over systemic racism and policing.

"She's out here touting a national plan" for criminal justice reform, said Mike Cantone, an Orlando liberal activist who previously supported Demings' bid for Congress. "But she's never once called for that kind of reform right here in her backyard."

In a recent interview, Demings argued she used the tools available to her to address excessive force and bad actors on the police force.

"I think people don't really fully understand sometimes the restraints that law enforcement executives have as it pertains to discipline," she said.

She insisted she "found some creative ways to get around" those rules and developed her own way "to force officers who I believed should not have been law enforcement officers to resign, pending termination."

In retrospect, Demings says, one of her biggest problems is that throughout her career, she's not been the flashy or outspoken type, and didn't speak up publicly about those efforts. Her parents, she said, "taught me to be pretty humble."

"If you use an 'I' too many times, it's just not who I am." she said. "I just tried my best to do what was right. I did what I could, when I could."

Demings speaks of her childhood with a cheeriness that belies the difficulties she faced as the youngest of seven, the daughter of a maid and a janitor and a descendant of slaves, growing up in a two-bedroom house in Jacksonville, a city known for its history of racial unrest.

In sixth grade, she was part of a group of Black students bused to a predominantly white school 15 miles from home as part of desegregation.

"Being the first Blacks to integrate Loretta Elementary School wasn't always the best, most fun experience," Demings said. "People remind you daily that you are different from the majority, and sometimes in a very cruel way."

Demings recalled a time when she wanted to sleep over at a white friend's house in sixth grade, and the girl's mother refused.

"We don't want that N- in our house," the mother told her daughter, Demings said.

But she made the most of that tough place. In junior high school, she and Hartley won first place in the school talent show, dancing and singing to Aretha Franklin's "Respect." In high school, she was on student council, was captain of the band's flag corps, played softball, and was elected Miss Congeniality.

"I did my dance routine and ended with the robot, and all the kids went wild," she said of the performance that won her Miss Congeniality.

Demings worked her way through college at Florida State University, majoring in criminal justice. She was a social worker before starting at the police academy, with no small amount of ambivalence about the idea.

But it would be a significant move — to Orlando, a city she didn't know well; into a job that was still majority white and male. Her plan, she said, was "to stay under the radar, not draw attention to myself."

And then her classmates in her police academy class asked her to run for class president.

"I'm not sure why I said yes — I think it was just to overcome, and to just, don't let fear paralyze you," she said.

Up against two other white men for the job, Demings won by a landslide.

She rose through the ranks over the next few decades until she became the Orlando Police Department's first female chief in 2007. She led a force that has grappled with a long record of excessive-force allegations, calls for reforms and more transparency for years before, during and after her tenure, which ended in 2011.

From 2010 to 2014, the department faced at least 47 lawsuits against the department's officers and paid out more than $3.3 million in damages, according to an investigation by local news station WFTV.

And an Orlando Sentinel investigation covering the same period found that Orlando officers used force in 5.6% of arrests — more than twice the rate of some other police agencies — and used force disproportionately against Black suspects.

Demings' defenders note she was credited with reducing violent crime in the city by 40% at the time of her retirement from the department in 2011, something John Mina, the current sheriff of Orange County, said was a priority of hers, along with improving communication with the city's under-served areas.

"She's very direct and a good communicator," he said. "She had really good vision of what she wanted to get accomplished. She communicated that vision."

After she retired as police chief in 2011, Orlando Mayor Buddy Dyer encouraged Demings to talk to national Democrats about a run for Congress. Demings was initially reluctant, he said.

"It took convincing to get her to go talk to them the first time," he said. "I don't think she'd ever considered it."

She lost her bid to incumbent Republican Rep. Daniel Webster, but ran again in 2016 after the district was redrawn in a manner that was more favorable to Democrats. This time, she won.

On Capitol Hill, her background in law enforcement helped boost her profile. She was tapped as one of the impeachment managers for House Democrats, the only non-lawyer chosen to try the case in the Senate.

The impeachment trial was Demings' first big stage in national politics. But it also served as a reminder of the racism that still persists for Black women in public life.

"One lady called my district office and said, 'Well, why is she trying to dress like a white woman?'" Demings said. "There were people who called and said I was just the most disgusting thing, or talked about my hair, my clothes, my looks, said I was the ugliest person they'd ever seen."

But in the same breath, Demings returned to the lessons her parents taught her as a child.

"There will always be people who try to put obstacles in your way and remind you that you're different," she said. "And you've got to push back."

Alexandra Jaffe and Tamara Lush report for the Associated Press.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

US Judge Dismisses Lawsuit Brought Under NYC Gender Violence Law, Ruling Claims Barred Under State Measure

No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

5 minute read

Second DCA Greenlights USF Class Certification on COVID-19 College Tuition Refunds

3 minute read

Florida Law Firm Sued for $35 Million Over Alleged Role in Acquisition Deal Collapse

3 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250