The Goldman Sachs headquarters in Manhattan, New York. Photo: Ryland West/ALM

The Goldman Sachs headquarters in Manhattan, New York. Photo: Ryland West/ALM In Private, Bankers Discuss Nuclear War and Russian Trading Risk

For all the months of warnings and scenario planning, Russian tanks crossing the border has left bankers scrambling.

February 25, 2022 at 03:30 PM

5 minute read

International banks are talking publicly about how the business impact of Russia's Ukraine invasion will be limited. In private, they're debating the chances of nuclear conflict.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. on Thursday put its clients on the phone with Alex Younger, ex-chief of Britain's MI6 intelligence service and now an adviser to the Wall Street giant. It's the first time in more than 30 years that the threat of nuclear confrontation is a real possibility, he said.

The episode is a jarring example of how the banking world is lurching into unknown territory with this conflict, in the same way as everyone else. For all the months of warnings and scenario planning, Russian tanks crossing the border has left bankers scrambling.

Firms such as Deutsche Bank AG and Commerzbank AG were eager to say on Thursday that their direct financial exposure to Russia was "well contained" and "manageable." They have a point: Only France's Societe Generale SA, Italy's UniCredit SpA and Austria's Raiffeisen Bank International AG have a substantial on-the-ground presence in Russia.

But the indirect costs of the new barrage of sanctions being unleashed by the White House, Brussels and 10 Downing Street are far harder to quantify. The EURO STOXX index of leading European bank shares has fallen about 11% this week as investors weigh up the risks to the broader economy and to the trading and private-wealth operations of the finance industry.

Banks have been locked in urgent mapping exercises to try to work out their trading exposure to counterparties backed by Russian money, according to a lawyer who works with many large financial institutions.

UBS Group AG moved quickly to limit its exposure to Russian assets on Thursday, triggering margin calls on some wealth clients that use Russian bonds as collateral.

Wall Street firms aren't immune. Banks such as JPMorgan Chase & Co., Citigroup Inc. and Bank of New York Mellon Corp. move vast amounts of money around the world via their treasury services businesses, which makes them de facto enforcers of sanctions. Any time a transaction with a sanctioned entity comes through, the banks have to block and freeze.

"Even if you don't directly have a Russian sanctioned bank as a client you're not entirely sure whether the transaction you're handing will go through a Russian bank," Eric Li, head of transaction banking at Coalition Greenwich, said. "The chain is very complex."

Russia isn't Iran, North Korea or Venezuela, with their limited links to global business. Banks have to dig through the myriad ways they can wind up with an exposure to an economy and finance system as big as Russia's — or to the wealthy bunch of oligarchs who've been enriched under Vladimir Putin's rule.

Banks also have to confront a striking geopolitical risk: Russia is a nuclear state, and Putin took the Cold-War era step of boasting about its arsenal in a speech trying to rationalize the invasion. President Joe Biden was even asked Thursday whether he thought Putin was threatening a nuclear strike. "I have no idea what he's threatening," Biden told reporters at the White House.

The comprehensive nature of the Russia sanctions is unprecedented.

On Thursday afternoon, Biden unveiled a raft of new measures, including freezing the assets of four major Russian banks, Sberbank PJSC and VTB Bank PJSC among them. Clay Lowery of the Institute of International Finance said the new measures are aimed at causing domestic bank runs, among other things.

"These sanctions will have a significant impact on Russia's overall economy, and average Russians will feel the cost," Lowery said. But the impact on foreign lenders from these specific curbs is expected to be limited because "existing sanctions, the risk of additional measures, and over-compliance have led many to scale back engagements" already, the IIF wrote in a recent report.

Biden and British prime minister Boris Johnson decided to hold off on cutting Russia's access to Swift, the global messaging system for the world's financial institutions. The option is still on the table for future retaliation.

In the finance industry, there's a question of whether an exit from Swift would cause as many problems for international banks as for the Russian government.

Biden's targeting of a broad swath of Russian elites and their family members, following a similar move by Johnson will be of greater concern to banks with large wealth management operations, especially those in Europe. Swiss private banks are historically a prime destination for Russian money, as is the City of London.

"In terms of oligarchs involved there's a lot to unscramble here and there are fire drills happening everywhere around London," said Michelle Linderman, sanctions lawyer at Crowell & Moring.

Harry Wilson, Hannah Levitt and Nishant Kumar reports for Bloomberg News.

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

6 minute read

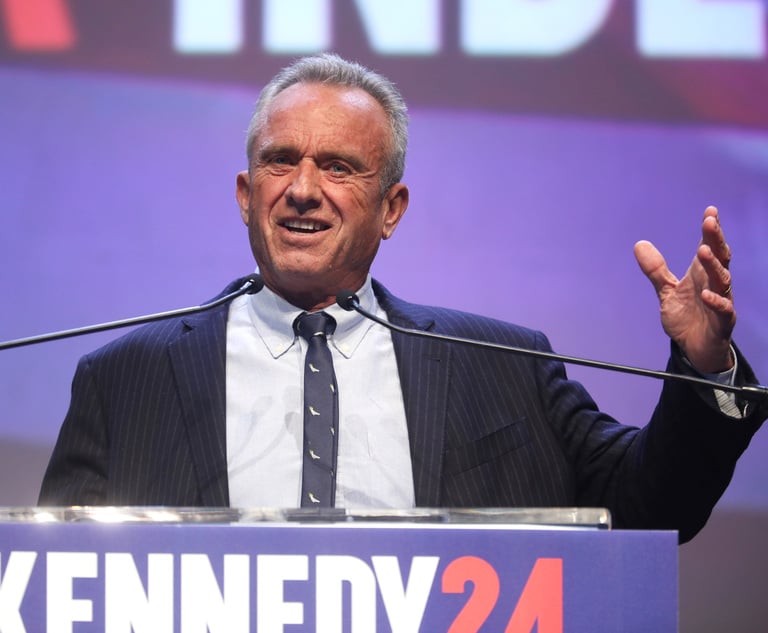

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 2Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 3Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 4Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

- 5Zoom Faces Intellectual Property Suit Over AI-Based Augmented Video Conferencing

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250