Ex-Alston & Bird Partner Defends Work for Client Suing for Malpractice

Former Alston & Bird partner Jack Sawyer took the witness stand Friday to defend his representation of a family-owned company whose ex-manager is accused of stealing about $1.5 million.

February 20, 2018 at 03:18 PM

6 minute read

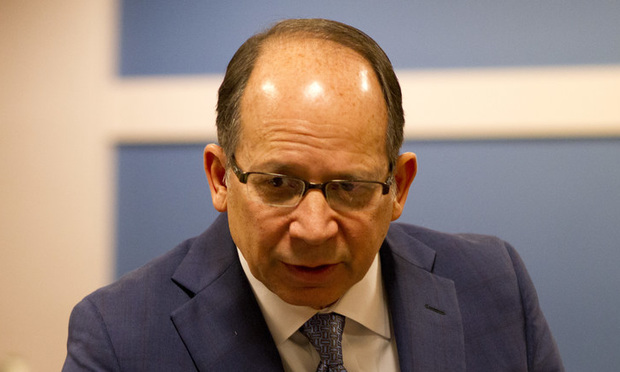

As the first week of trial in the legal malpractice suit against Alston & Bird concluded Friday, former partner Jack Sawyer—accused of mishandling a family company's affairs and allowing the eldest sibling to abscond with about $1.5 million—took the witness stand to rebut the earlier pummeling he took at the hands of plaintiffs counsel.

Sawyer said he was as surprised as anyone to learn former manager Maury Hatcher cashed out his interest in the family company, Hatcher Management Holdings LLC, paying himself an inflated price on top of hundreds of thousands of dollars in self-dealing fees.

“I assumed that, if he decided to go forward [in selling his interests], I would be notified in advance,” said Sawyer, who began discussing with Hatcher in late 2008.

Maury had been fending off queries about company finances and distributions from younger brothers, Jerry and Barry Hatcher. In January 2009—when Maury announced he would resign at month's end—his brothers presented what they said was a ballot of family members naming them co-managers.

Sawyer and another Alston & Bird partner he brought on, Nowell Berreth, are accused of helping Maury deny company members' access to financial records and documents after he was no longer the manager.

In one email after his effective resignation, Maury wrote to Berreth that he wanted to keep the records from being turned over until his brothers agreed to a “universal release for everyone.”

“I view your holding the records as a degree of leverage,” Maury wrote.

The company and several family members sued Maury, who failed to appear for trial, in late 2009. The court entered a default judgment against him for more than $4 million in 2013. He never paid it and is not a witness in the ongoing trial.

Hatcher Management sued Alston & Bird for legal malpractice and breach of fiduciary duty in 2013, arguing Sawyer knew about Maury's plans to cash out and even helped him write a “cease and desist” letter to Jerry and Barry after they told him they had assumed management duties.

Sawyer was called as the first plaintiffs witness and underwent questioning about his knowledge of Maury's plans and role in drafting the company's operating agreement. The plaintiffs lawyers, Harmon Caldwell Jr., Harry MacDougald, Jeremy Moeser and Christine Dial of Caldwell, Propst & DeLoach, have accused Sawyer of deliberately drafting the agreement to allow Maury to hide information such as his own salary and the distributions paid to family members.

The defense's case has yet to begin, but Sawyer was called out of turn Friday because he is not available this week.

A tax and estate lawyer with 37 years in practice, Sawyer left Alston & Bird last year after 28 years at the firm.

Under friendly questioning by Robbins Ross Alloy Belinfante Littlefield partner Jeremy Littlefield, Sawyer described his relationship with the company and Maury as one in which he occasionally provided advice after being retained to draft the operating agreement in 2000.

Sawyer said claims he drafted the agreement to hide details like the members' shares are misguided, because he did not know the relative value of those shares at the time. He also disputed that the agreement allowed Maury to set his own pay.

Sawyer said no family members contacted him with concerns, and in early 2009—after Maury had apparently resigned and Jerry and Barry were contacting banks and a company tenant saying they were running the company—he agreed to send a “cease and desist” letter Maury requested while the management dispute was sorted out.

“The whole thing was up in the air,” said Sawyer, who along with Berreth had Maury bring the company's records to Alston & Bird's offices and arranged for them to be copied and turned over to Jerry and Barry.

Littlefield, defending Alston & Bird with firm partners Richard Robbins and Jason Alloy, asked whether Sawyer believed he had worked in his client's best interests.

“I believe that with all my heart,” Sawyer said.

That assessment was challenged by plaintiffs expert David Hricik, a professor of legal ethics at Mercer University School of Law.

Hricik said Sawyer and Berreth should have first ascertained who their client was before helping Maury stiff-arm his brothers and the company.

“If you're in a position where you're uncertain, the first thing you do is help the client figure it out,” said Hricik. “The one you clearly don't communicate with is is Maury … who's trying to get leverage out of the files.”

Robbins, leading Alston & Bird's defense, laid into the professor as a “preaching” academic who failed to recognize the “real world” decisions lawyers face.

“It's easier to tell people what to do rather than do it yourself, wouldn't you say?” asked Robbins in one of the testy exchanges.

“Lawyers like Jack Sawyer and Nowell Berreth are in the trenches every day making judgment calls,” Robbins said.

Robbins also slammed Hricik for acting as a hired expert against Sawyer, noting the professor is of counsel with Taylor English Duma, where Sawyer is a recent partner.

“Wouldn't you agree that it's a conflict of interest for you to voluntarily take money to testify against a partner in your firm?” Robbins demanded.

Hricik retorted that he was involved in the case for several years and that Sawyer—whom he has never met—signed on with Taylor English “three or four months ago.”

“Would it have been ethical for me to have quit after 10 years?” Hricik asked, addressing the jury. “Would that have been fair to the plaintiff, to the judge, to all of you?”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Appellate Court Finds Trial Court Wrongly Dismissed Legal-Malpractice Suit Despite Disqualifying Counsel a Week Prior

Herschel Walker's 2022 Campaign for Senate Sues Media Agency for Inflated Ad Costs

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250