Fisher Phillips Witnesses Detail Pay Cuts for Tex McIver Before Wife's Shooting

Fulton County prosecutors contend that Tex McIver shot and killed his wife to maintain his diminishing wealth and secure his beloved ranch that he had mortgaged to her for a $350,000 loan he couldn't pay. Fisher Phillips executives detailed the extent of the salary cuts to a jury in McIver's ongoing murder trial.

March 13, 2018 at 08:11 PM

7 minute read

The managing partner and the chief financial officer of Atlanta's Fisher & Phillips testified Tuesday that Claud “Tex” McIver was stripped of his status as an equity partner in 2013 and that, beginning Jan. 1, 2014, became an income partner at greatly reduced pay.

For the first seven years of the employment lawyer's marriage to Diane McIver—president of Atlanta advertising firm U.S. Enterprises—Tex McIver's annual earnings averaged more than $570,000 a year, Fisher Phillips CFO Jim Nations testified Tuesday at McIver's murder trial. But in 2013, McIver's earnings plummeted by nearly $140,000 to $435,603, Nations said. By the end of 2014, McIver's first year as an income partner, his annual pay dropped again—to $350,000, Nations said. And, as an income partner, McIver was no longer eligible to draw a percentage of the law firm's total annual profits, he said.

That would not be McIver's only pay cut, according to Nations and Fisher Phillips managing partner Roger Quillen, who testified Tuesday afternoon. McIver worked at Fisher Phillips for 44 years until he retired under duress after he shot his wife to death in what he and his attorneys have claimed was a tragic accident. Fisher Phillips is a midsize law firm specializing in labor employment law, primarily defending employers against workers' claims.

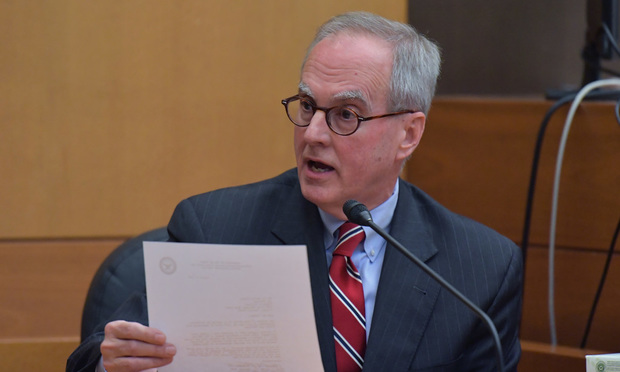

Jim Nations, chief financial officer, Fisher & Phillips (Photo: Hyosub Shin/AJC)

Jim Nations, chief financial officer, Fisher & Phillips (Photo: Hyosub Shin/AJC)Nations said McIver's earnings dropped yet again—to $275,000—for the fiscal year that ended only four days after Diane McIver's Sept. 26, 2016, death.

The law firm executives testified following opening statements in Tex McIver's murder trial. Fulton County prosecutors contended that, when he shot his wife, McIver was financially strapped, struggling to maintain a high-end lifestyle on a rapidly eroding salary and in hock to his wife for a $350,000 loan he had secured with his interest in their 75-acre ranch southeast of Atlanta.

Fulton County Chief Senior Assistant District Attorney Seleta Griffin also argued that Diane McIver's death provided her husband, who she said otherwise “didn't have a dollar,” with an immediate cash windfall totaling more than $1 million.

McIver was named as the executor and primary beneficiary of his wife's 2006 will, which is being contested in sealed proceedings in Fulton County Probate Court. Prosecutors contend, based on multiple statements by friends and colleagues of Diane McIver, that she had executed a second will—that no one has ever located—that likely would have greatly reduced her husband's benefits in favor of the couple's godchild, the son of Fulton County Superior Court Judge Craig Schwall.

Quillen testfied that he first met Tex McIver when McIver interviewed him for a job in 1979. Quillen joined the firm in 1980.

Quillen told the jury Tuesday what had led the law firm to demote McIver from equity partner to income partner: “It often happens in the career of one of our partners as they advance in the number of years of practice or at an age that their performance begins to diminish in relation to performance standards we have in relation to equity partners of the firm. … If it appears to be a steady, diminishing level of performance, we ask the partner if [he] will agree to … become an income partner.”

“It is,” Quillen added, “ a reduction in compensation” with a lower level of performance standards that are based not only on billable hours but also on additional “standards of business development.”

Equity partners, he said, are expected to bill at least 2,000 hours a year and to develop new books of business. Lawyers are given specific dollar goals, both for originating clients and for dollars in services generated, either on behalf of their own clients or those originated by someone else at the law firm.

Salaries are based on rolling three-year performance records. By 2013, McIver's billable hours had dropped substantially below that goal, Quillen said—an indication that the firm was already channeling him toward a change from equity to income partner.

Quillen said McIver wasn't meeting his reduced annual billable-hour goals and, though between 2014 and 2016 McIver generated more than $1 million in business development dollars, he was still missing his annual goals “by a wide margin.”

“Absolutely, that standard is never less than $1.5 million,” Quillen said. “It could possibly have been more. It definitely was not less.”

Quillen said that “long before” Diane McIver's death, firm management had initiated conversations with McIver about a retirement plan that would result in his stepping down as income partner by the end of 2017 to become senior counsel.

As senior counsel, McIver would be paid a contingency fee, usually 20 or 30 percent of hours billed on the firm's behalf.

Quillen said that, after McIver shot his wife, the firm placed him on extended bereavement leave and continued to pay his salary as an income partner.

“As we moved late in the year, we began to feel that the chances of Tex ever being able to return his full attention to the business of his clients and the business of the firm was highly unlikely,” Quillen said.

Quillen said that, if Diane McIver had not been shot, the firm was looking at “that very deep drop in performance hours and billable hours and in business development, and we would have reduced his compensation by a very, very deep amount.” But, he said, the firm already had plans to cut McIver's salary again—to $150,000—in 2017 before he would become senior counsel.

McIver was informed that the firm had changed its plans and intended that McIver retire by the end of 2016. “Initially, he was not really inclined in that direction. He told us so,” Quillen recalled. “He expected that … he would be able to return his attention to clients and the interests of the firm. … He was really hopeful this thing facing him would be behind him. After mental adjustment time, he was hopeful he would get back to performing at a higher level.”

By Dec. 16, 2016, five days before McIver was charged with felony involuntary manslaughter and reckless conduct associated with his wife's shooting, Fisher Phillips' management committee had decided that McIver had to go. “It needs to be a clean break,” Quillen said McIver was told. McIver was also informed that, as of Jan. 1, 2017, he would have “no continuing status” at the firm.

“We do not want you to engage in the practice of law following retirement and think its a bad idea to do that,” Quillen said he told McIver in an email. McIver's name, he said, would no longer appear on the firm's website, and the firm no longer wanted him to refer either work or clients. Quillen said McIver was also told, “We think it would be inconsistent to have you marketing on behalf of the firm, and we don't encourage you to do that.”

Quillen said the firm was prepared to pay McIver $180,000 in severance. But McIver never signed the severance agreement.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Sunbelt Law Firms Experienced More Moderate Growth Last Year, Alongside Some Job Cuts and Less Merger Interest

4 minute read

Fowler White Burnett Opens Jacksonville Office Focused on Transportation Practice

3 minute read

Georgia High Court Clarifies Time Limit for Lawyers' Breach-of-Contract Claims

6 minute read

Southeast Firm Leaders Predict Stability, Growth in Second Trump Administration

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Plaintiff Argues Jury's $22M Punitive Damages Finding Undermines J&J's Talc Trial Win

- 2Bannon's Fraud Trial Delayed One Week as New, 'More Aggressive,' Defense Attorneys Get Ready

- 3'AI-Generated' Case References? This African Law Firm Is Under Investigation

- 4John Deere Annual Meeting Offers Peek Into DEI Strife That Looms for Companies Nationwide

- 5Why Associates in This Growing Legal Market Are Leaving Their Firms

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250