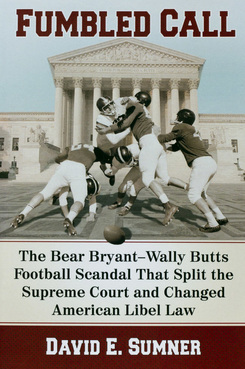

Book Recalls 1960s Georgia-Alabama Football Scandal, Libel Case

"Fumbled Call" revisits a dramatic Atlanta trial involving big football and big lawyers.

May 08, 2018 at 12:18 PM

5 minute read

Today we worry about online pirates stealing personal information and nefarious foreign governments hacking into our democracy. So what happened in September 1962 to Wally Butts, the athletic director at the University of Georgia, and Bear Bryant, the legendary football coach at the University of Alabama, seems quaint.

Butts, who'd resigned under pressure as UGA's football coach in 1960, was visiting an Atlanta public relations firm when he placed a call to Bryant at his Tuscaloosa campus. At the same time, an Atlanta insurance salesman named George Burnett telephoned a friend at the same PR firm.

Burnett would testify that, instead of his friend on the other line, he heard unusual electronic noises, a long distance operator seeking “Coach Bryant” and then the voices of Butts and Bryant.

“Hello, Bear,” Butts said.

“Hello, Wally, do you have anything for me?” Bryant responded.

Burnett said that Butts had plenty for Bryant, whose Crimson Tide was hosting the Georgia Bulldogs the following week. Burnett said Butts advised that Georgia's pass defense was weak except for Blackburn, that the offense used his old “29-0 series” and a “left end out-15 yards” play and not to worry about quick kicks, because Georgia didn't have anyone who could pull off that surprise play. Bryant asked some questions to which Butts didn't know the answers, so Bryant promised to call Butts a few days later, which telephone records said occurred and lasted one hour.

Six months after Alabama trounced Georgia 35-0, The Saturday Evening Post reported Burnett's account as “The Story of a College Football Fix”—and Butts sued the magazine for libel.

“Fumbled Call” by David E. Sumner, a retired journalism professor at Ball State University in Indiana, examines the scandal and the libel trial that led to a splintered 1967 U.S. Supreme Court decision. Although the ruling was a loss for the magazine publisher, the case's significance was that it has been interpreted to hold that “public figures” such as football coaches must prove actual malice to prevail in libel cases. That is an expansion of the court's 1964 New York Times v. Sullivan decision that placed that heavy burden of proof only on “public officials.”

Sumner works mostly from transcripts and documents, which I initially thought gave the book a ponderous, academic feel. But one afternoon I was so engrossed in it on a MARTA train, I forgot to get off at my home station, so Sumner must be doing something right.

Burnett's predicament upon hearing the call—and taking contemporaneous notes—is particularly compelling. As Sumner writes, shortly after Burnett confided what he heard, “it took on a life of its own. This former war hero and shy insurance salesman was about to become trapped between the forces of big-time college football, big-time coaches, and big-time lawyers.”

Indeed, the lead lawyer for Butts was William Schroder of Troutman, Sams, Schroder & Lockerman, a predecessor to today's Troutman Sanders. (Co-founder Carl Sanders was governor of Georgia during the scandal; he ordered the state attorney general to investigate the Butts-Bryant call.)

Wellborn Cody of what was then Kilpatrick, Cody, Rogers, McClatchey & Regenstein—now Kilpatrick Stockton & Townsend—represented Curtis Publishing Co., the magazine owner.

Sumner takes us into the Forsyth Street courtroom of U.S. District Judge Lewis Morgan (who amazingly neglected to disclose that he attended the Alabama-Georgia contest that some claimed was fraudulent.)

There we see Schroder and Cody battle the case with varying degrees of skill and success. Despite Burnett's damning testimony backing the magazine article, Cody doesn't know football like Schroder, who gains ground with star witnesses like Bryant and Butts. The coaches make statements that conflict with earlier reports about their interactions, but, as Sumner reports, they dazzle the jurors with arcane football talk during discussions about whether any information gleaned from Butts would have made a difference in the game.

Cody also suffers from the actions and omissions of his clients at The Saturday Evening Post. No one from the magazine came to Atlanta to testify, and their defense statements in affidavits and depositions paled in comparison to Schroder's live gridiron heroes.

Worse, Sumner notes, the article was rushed to print, without typical fact-checking. Although Burnett's testimony more than suggested something was very wrong, the situation didn't match a “fix” trumpeted in the headline in which gamblers stood to profit from the inside information.

Certainly by today's standards, the Post committed two glaring no-nos: The magazine paid Burnett $5,000 for his story—and didn't disclose that fact to readers—and the magazine did not appear to ask Butts, Bryant or anyone else to comment on Burnett's claims. I was surprised that Sumner, a journalism professor, didn't take more note of these flaws.

As much as Sumner succeeds in bringing the scandal and the trial to life, he gives only three pages of analysis to the high court's handling of the case. I know the challenge of reporting a multiopinion, plurality decision of an appellate court, and I credit Sumner for boiling it down to a few pages. But, given the subtitle to the book is, “The Bear Bryant-Wally Butts Football Scandal That Split the Supreme Court and Changed American Libel Law,” I expected more.

Fortunately, there is a place to get more of this tale. There is video of the 2016 Georgia Bar Media & Judiciary Conference, which held a panel discussion on the case. I was on the planning committee of the event, which was moderated by former Atlanta Journal-Constitution managing editor Hank Klibanoff and featured Sumner and Emmet Bondurant of Bondurant Mixson & Elmore, who assisted Wellborn Cody on the matter.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trump RTO Mandates Won’t Disrupt Big Law Policies—But Client Expectations Might

6 minute read

Trump's RTO Mandate May Have Some Gov't Lawyers Polishing Their Resumes

5 minute read

Big Law Practice Leaders Gearing Up for State AG Litigation Under Trump

4 minute read

Few Atlanta-Centric Law Firms Expected to Pay Associate Bonuses at Market Scale

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1We the People?

- 2New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 3No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 4Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 5Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250