Northside Hospital, Jones Day Partner Lock Horns Again at Court of Appeals Over Whether Hospital Records Are Public

A public records fight over documents associated with Northside Hospital's $100 million acquisition of four private medical practices has pitted the hospital against a Jones Day partner who may be suing on behalf of an anonymous client.

May 16, 2018 at 07:46 PM

5 minute read

The high-stakes battle over whether records from an Atlanta hospital's $100 million acquisition of four private medical practices are subject to open records laws returned to the state Court of Appeals for the second time Wednesday.

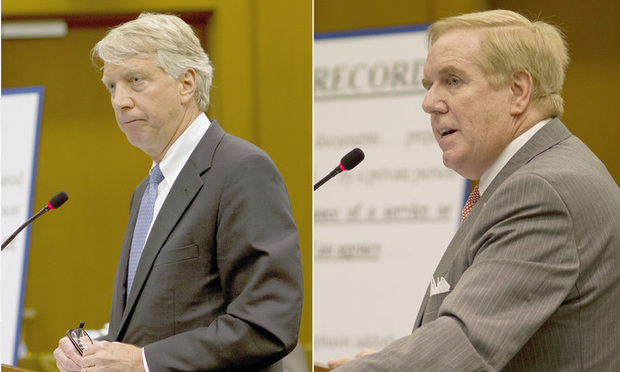

Attorneys representing the hospital and its nonprofit parent company—led by Dentons partner Randy Evans—squared off against Jones Day partner Peter Canfield, who is representing fellow partner Kendrick Smith.

Wednesday's appellate panel, which included Chief Judge Stephen Dillard and Judges John Ellington and Christopher McFadden, heard oral arguments on whether Smith can be compelled to reveal why he sought records that hospital lawyers claim are confidential trade secrets, and whether he is acting on behalf of an anonymous Northside Hospital competitor seeking a business advantage.

The state Supreme Court unanimously reversed the lower courts in November and remanded the case with instructions to determine whether the acquisitions Smith sought to examine would qualify as actions taken on behalf of the Fulton County Hospital Authority, which is subject to the state open records laws.

The high court also directed the trial court to make a separate determination on whether the sought-after records are trade secrets that are exempt from the open records law.

But before the case was sent back to Fulton County Superior Court Judge Gail Tusan, Northside lawyers persuaded the state appeals court to reopen their earlier cross-appeal to reverse a protective order Tusan issued that barred Northside from questioning Smith about his possible client or his motive. The appellate court said there was no need to consider it at the time.

During oral arguments Wednesday, Evans said Smith and his counsel used the protective order as cover to conduct a “vitriolic, vicious attack” on Northside, intimating the hospital engaged in illegal kickback schemes and other fraudulent conduct. But Evans said that when he sought to question Smith about the allegations, Smith cited the protective order in declining to answer.

McFadden, who dissented from the appeals court's earlier decision affirming that the sought-after records were not public, challenged Evans' contention that he had a right to know whether Smith was acting on behalf of a Northside competitor.

But Evans said that once Smith elected to testify, “The defendant is entitled to cross-examine them on the basis of their statements. Mr. Smith took the witness stand. I didn't call him. They called him … Tell me where in the statute it says cross-examination is allowed—except in a GORA [Georgia Open Records Act] case?”

Canfield countered that questions about Smith's reasons for seeking the records, or whether he was doing so at a client's behest are irrelevant to whether the records should be public.

“As someone who has been trying open records cases for decades, I don't believe I have ever had a case where requesters [of public documents] have been subjected to discovery, much less the relentless kind of discovery Northside has pursued with Mr. Smith,” he said.

Canfield also took umbrage with allegations that he or Smith made “scurrilous” assertions about why Northside might want to keep the records under wraps.

“We pointed out there are many reasons why they are legitimate public records,” he said, citing a report in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution that cancer patients' costs increased tenfold when the private medical practices merged with Northside.

“These kind of health care transactions are the most regulated legally,” he said. “There are all sorts of compliances. There is certainly a general public interest in seeing that.”

Canfield also argued that public record custodians generally have no legitimate reason to ask why records are being requested. “The question is whether the public has a right of access to these records, not whether any private person has a right,” he added

“Northside obviously doesn't like the fact that an attorney brought these open record requests,” Canfield continued. “Attorneys are allowed to bring open records requests … The statute permits that. I suspect here in Georgia, public record requests generally come more from lawyers than anyone else.”

And, he argued, “To permit the kind of questioning Northside seeks to do here would impinge on attorney-client privilege.”

Asked by Dillard whether the records would be exempt from disclosure as trade secrets, Canfield said not in this case. While hospital authorities and nonprofits like Northside may withhold documents as trade secrets under the law, those records are subject to disclosure once the transaction is approved or rejected.

“Here, the approval occurred long before the request was made,” he said.

Canfield also said Evans couldn't question Smith's motives in an effort to make a case that the documents are trade secrets.

“You don't prove your records are subject to the trade secrets exemption just because somebody asked for them, [or] that the requester represents some competitive interest,” he said. “You show it by looking at the nature of the record … You have to do it by submitting the records for in camera inspection. We have asked Northside to do that in this case. They have refused.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Sunbelt Law Firms Experienced More Moderate Growth Last Year, Alongside Some Job Cuts and Less Merger Interest

4 minute read

Fowler White Burnett Opens Jacksonville Office Focused on Transportation Practice

3 minute read

Georgia High Court Clarifies Time Limit for Lawyers' Breach-of-Contract Claims

6 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Pistachio Giant Wonderful Files Trademark Suit Against Canadian Maker of Wonderspread

- 2New York State Authorizes Stand-Alone Business Interruption Insurance Policies

- 3Buyer Beware: Continuity of Coverage in Legal Malpractice Insurance

- 4‘Listen, Listen, Listen’: Some Practice Tips From Judges in the Oakland Federal Courthouse

- 5BCLP Joins Saudi Legal Market with Plans to Open Two Offices

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250